When 24-year-old Yulu Chen created a WeChat group called Nüshu Sisterhood Chat, she expected only a handful of close friends to join.

Within months, the group hit the social media platform’s 500-member limit, prompting her to create more groups.

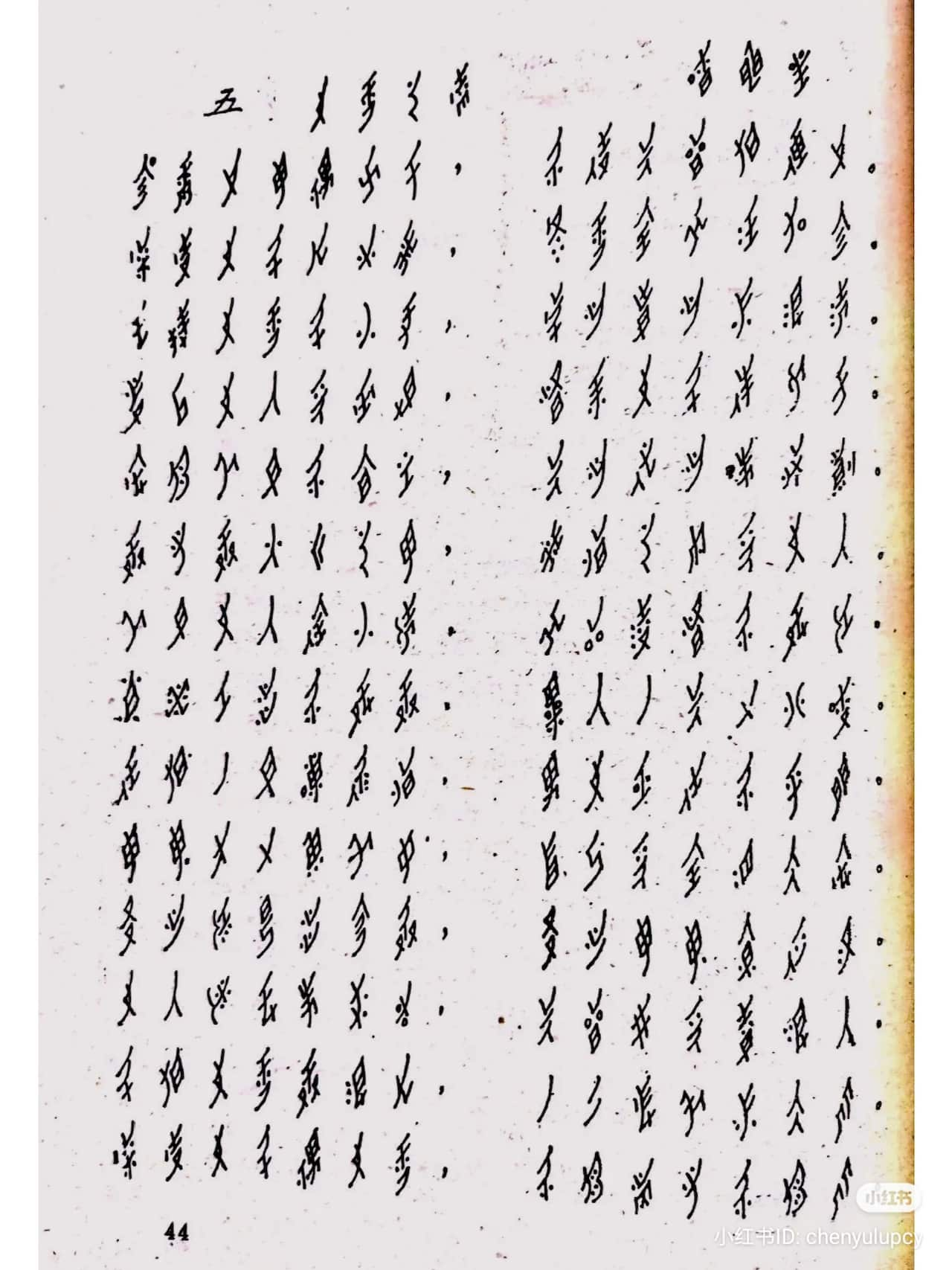

Nüshu — which translates to ‘women’s writing’ in Chinese — is an ancient syllabic script derived from Chinese characters and designed by women, allowing them to communicate secretly without men understanding.

Women saw the chat as a safe space to share details of their lives.

“What surprised me the most was how quickly women opened up,” Chen said.

“Nüshu became more than just a language. It became a way for us to share things we didn’t feel comfortable to say elsewhere.”

There could be as many as 1,000 Nüshu characters. Some writers and scholars have compared it to the footprints of birds or have called it ‘mosquito writing’.

‘Script of tears’

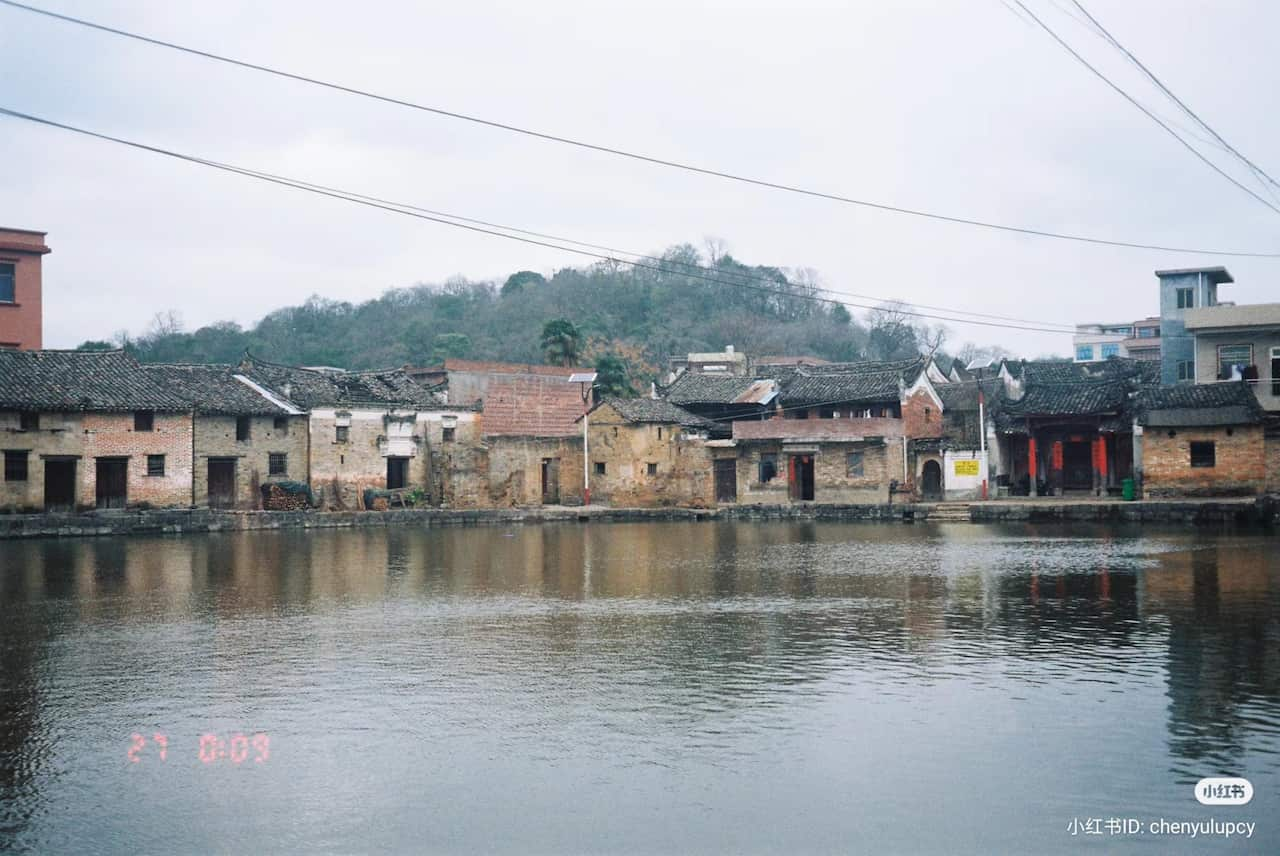

Some scholars trace Nüshu’s origins back 400 years to a time during the Qing Dynasty, in China’s Hunan province, where peasant women were isolated from public life and living in secluded villages.

They were barred from formal education and confined to their homes, often with bound feet.

Foot binding was a practice carried out on young girls and women to make their feet small. Small feet were considered beautiful and a symbol of obedience and subservience.

Sometimes referred to as the ‘script of tears’, Nüshu empowered women to communicate and express their deepest feelings — sorrow over unhappy marriages, family conflicts and separation from loved ones.

A photo of a child’s bound feet, from China in 1918. The ancient practice of footbinding involved breaking and tightly binding the feet of young girls for aesthetic purposes. The practice was banned in the early 1900s but did not truly end until the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. Credit: Duke University Rubenstein Libra/Gado via Getty Images

Nüshu was initially scrawled on the ground in wok ashes using tree branches.

The characters are formed with dots and three kinds of strokes — horizontals, virgules and arcs. These elongated letters are written with fine and thread-like lines, and skewed to fit a rhomboid shape where their Chinese counterparts are square.

The language is phonetic, with each character representing a syllable, whereas modern Chinese is a logographic language, meaning its characters represent specific words.

Nüshu was used to write poetry and songs on folding fans, embroidered on handkerchiefs, or even sewn into the collars and sleeves of clothing.

Creating secret spaces

Mirroring its ancient use, the group chats on modern China’s social media sites have become intimate and secret online spaces for women.

In these chats, women and young girls discuss Nüshu lore and history, call out misogynistic behaviours in other online forums, and plan meet-ups and trips to Jiangyong, the birthplace of Nüshu.

Sometimes, users share personal struggles — marital issues, divorce and domestic violence, and discuss the challenges of being a woman in modern Chinese society.

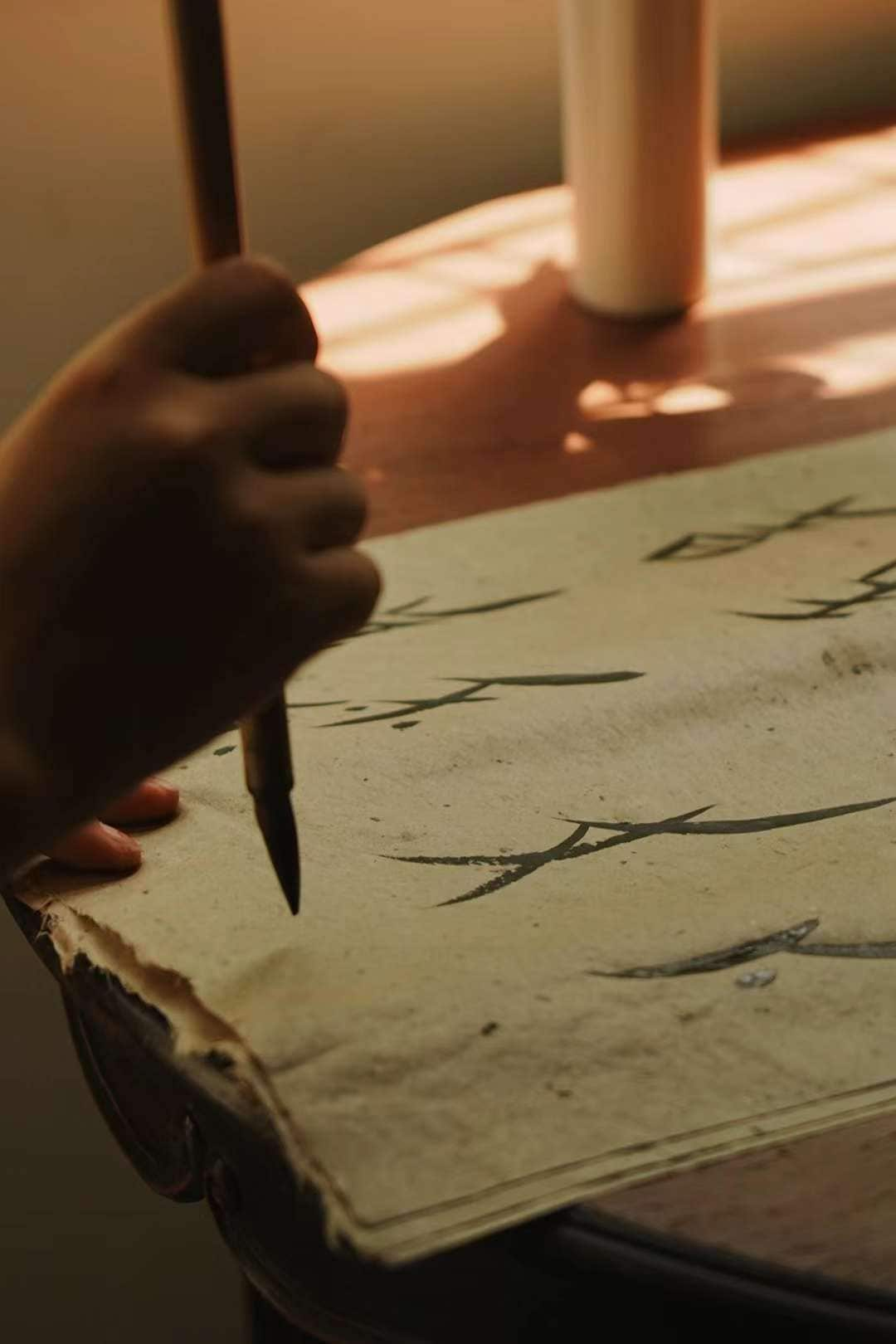

Yulu Chen practices writing in Nüshu for a documentary film she produced.

“Only women are allowed to join,” Chen explained. “You have to be invited by someone who knows you, and then you record your voice as proof before being added to the group.”

Nüshu group chats aren’t limited to WeChat. Other platforms such as QQ, Douyin and Little Red Book (RED) also host private groups where women gather to learn, practice and discuss Nüshu.

These digital spaces are monitored by the Chinese Communist Party, which once sought to destroy cultural relics it deemed feudal — including Nüshu books —during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s.

Source of strength and power

Chen’s interest in the secret language was piqued after moving to Shanghai to study photography.

“In China, there are very few female photographers,” she said.

“People are often surprised when I tell them what I do. They say: ‘Oh, there are actually female photographers?'”

Chen was exploring feminist themes for a university photography project when she came across Nüshu online.

Realising it came from Jiangyong, close to her hometown in Hunan Province in south central China, she knew it was the right choice for her project and travelled there.

But she discovered most Chinese people were not familiar with the script.

“When I asked people in the town about Nüshu, almost no one knew what I was talking about,” she said.

Jiangyong, a remote village from where the Nüshu language is thought to originate.

Eventually, Chen found a woman in her 80s who was one of the last living inheritors of Nüshu.

She showed her Nüshu calligraphy and told her tales of the women — including her grandmother, who had been able to write and sing Nüshu songs.

The more Chen learned about Nüshu, the more she understood its dual meaning — it brought both pain and strength to the women who used it.

“There’s a sort of power in being able to relate to women from hundreds of years ago through this language,” she said.

“The issues women face today are very much the same. I feel powerful knowing this.”

Jia Yi Chen has expressed the pain of family secrets through her Nüshu-inspired artworks.

Processing pain through language

For 25-year-old artist, performer and photographer Jia Yi Chen, Nüshu helped her process the pain of her upbringing.

Chen was born during the era of China’s one-child policy, when boys were valued over girls.

Her mother gave birth to her in secret.

At the age of 15, her parents revealed that her grandmother had prepared to throw her into the river at birth because she was a girl.

“My mother, who had just given birth and was very weak, ran to the river to pick me up so I could survive,” Jia said.

“That’s something that sticks with you. It makes you feel invisible, like your existence is irrelevant.”

The revelation led her to cut ties with her father’s family and, eventually, move to Edinburgh to pursue her artistic career.

During her studies of Chinese art, she learned about Nüshu, which prompted her to go to Jiangyong, where she visited the county’s Nüshu museum and met with inheritors of the script.

In March 2024, she created a photography exhibition in Edinburgh featuring Yao women from Jiangyong, dressed in traditional Yao clothing, with Nüshu characters drawn on their necks.

Jia Yi Chen uses a traditional Chinese calligraphy brush to paint Nüshu characters on her arms, which helps her process her inner thoughts.

She has also created a live performance piece in which she uses a traditional Chinese calligraphy brush to paint Nüshu characters on her arms while reciting stories and sharing the history of Nüshu.

Doing so has allowed her to work through her feelings around what happened to her.

“I want to write it down on my body in the form of Nüshu, but I don’t want my mum to know.

“Sometimes I want her to understand, but other times I don’t.

“Just like Nüshu, it’s a secretive and hidden language.”