This article contains distressing content and references to self-harm.

Sam* has always been drawn to sparkly things, says Alice, her grandmother and legal guardian.

She says the attraction might seem juvenile for the 14-year-old First Nations girl from Cairns, but people often misunderstand her capacity.

“People who don’t know her will think she is a normal teenager, but she’s not,” Alice said.

“I think living in this world is very scary for her.”

Sam has fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, known as FASD, and other severe intellectual disabilities. She has been found to have the mental capacity of a five-year-old and the language skills of a three-year-old.

“She’s unable to express emotion very clearly,” Alice said.

And if she feels threatened: “Her response is fight or flight.”

Sam is on the serious repeat offender list which means she’s targeted by Queensland’s specialist youth crime squad, Taskforce Guardian. She’s been arrested for petty offences and also acts of violence.

Taskforce Guardian was established in early 2023 in response to several high-profile youth crime incidents.

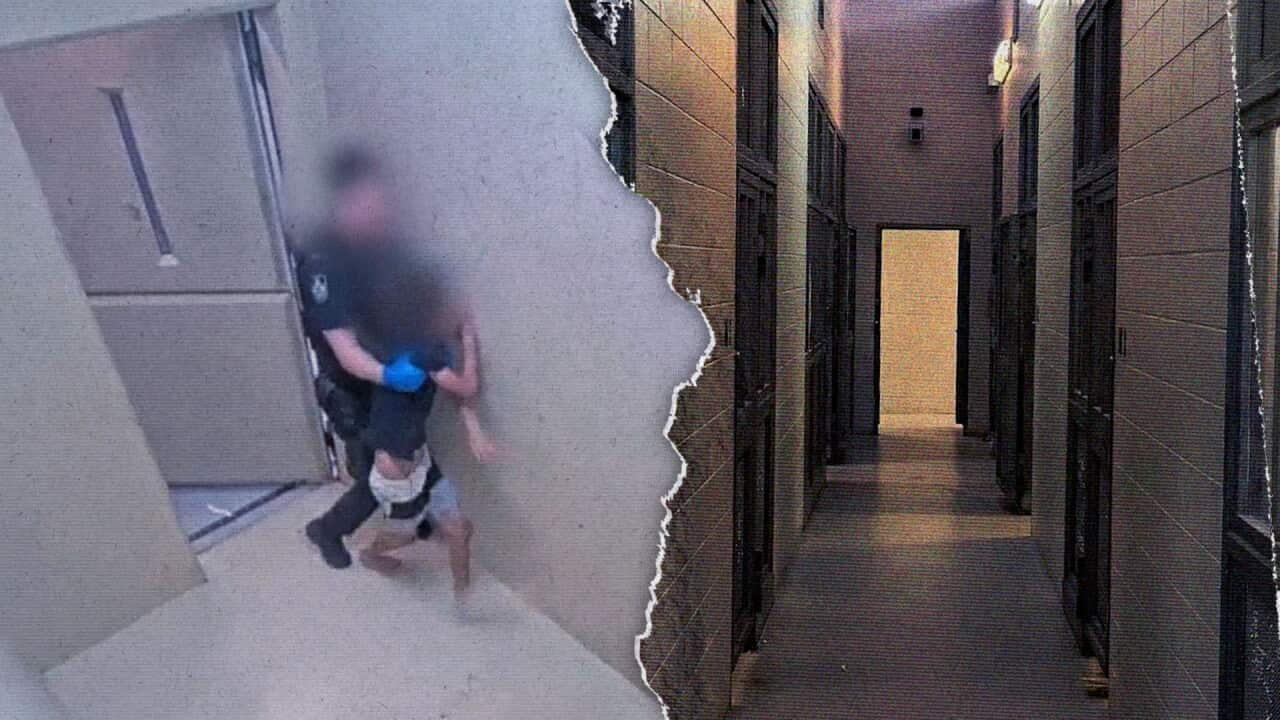

Watch houses are attached to police stations and are designed to hold the most violent and dangerous offenders when they pose a threat to themselves or others. Source: SBS

Sam has been in a watch house more than ten times

It’s August 2023, and Sam, who is 13 at the time, is being pulled into an isolation cell by Queensland watch house officers.

She is put into a cell known as ‘the box’. It’s meant to hold Queensland’s most violent and dangerous adult offenders when they pose a threat to themselves or others — but it’s also being used for children.

Sam is moved into an isolation cell after throwing toilet paper at a CCTV camera in the watch house.

Conditions vary in watch house cells; some might have a thin mattress, others have a blanket or a toilet in the open.

In ‘the box’, there is no mattress, toilet or window.

At the age of 13, Sam was placed in an isolation cell in an adult watch house. Source: SBS

In footage obtained by Guardian Australia and SBS The Feed, Sam can be heard pleading with officers. “It’s too cold in here,” she repeats. In the cache of videos obtained in this investigation, it’s not the only time a complaint of this nature has been made by children in watch houses.

In the footage, Sam becomes increasingly distressed as officers try to restrain her to keep her in the cell. As they leave the cell, and Sam follows, her hand gets caught in a closing door.

“You just did that to yourself,” an officer responds as she clutches her hand.

This was not Sam’s first time seeing the cell’s cream-coloured walls. Although she had been deemed unfit to stand trial by health authorities, she had been detained in an adult watch house more than 10 times.

In the same month Sam was placed in the isolation cell, Queensland suspended its Human Rights Act to detain children in adult watch houses. The controversial laws allow for children to be locked up in adult watch houses, which are typically attached to police stations.

Among 57 pages of amendments, the Queensland government also made provisions to retrospectively exempt itself from litigation for any likely unlawful practice in the past.

The debate around youth crime

Queensland locks up more kids than anywhere else in Australia, and 55 per cent are Indigenous.

In February, to mark the 1,000th arrest made by Taskforce Guardian, Queensland Police posted a video compilation of the body cam footage from the arrests.

But data shows youth crime rates are going down, and it is a small group who are committing crimes and re-offending.

The number of offences per young offender has been increasing over the past decade. Source: SBS

The number of child offences per 100,000 persons aged 10 to 17 has been trending down over the past decade. Source: SBS

The debate about youth crime has emerged as one of the key issues ahead of the upcoming state election — with many victims calling for a crackdown.

The Opposition has promised that if it wins the state election in October, it will change laws to try underage offenders as adults for serious crimes.

Inside watch houses

Katherine Hayes, CEO of the Youth Advocacy Centre, said kids as young as 11 are being detained in watch houses.

“They are designed to hold adults for maybe one night, two nights at most, if they’re drying out from a night on the drink or if they’re being violent or coming down from drugs,” she said.

Katherine Hayes, the CEO of the Youth Advocacy Centre, says there have been multiple reports of kids being denied access to food, family or blankets as a disciplinary measure. Source: SBS

With children held in the same facility as adults, there have been reports of men exposing themselves to children and young people being beaten up by cell mates or guards.

The advocacy body that Hayes heads is investigating at least one sexual assault committed against a child while they were being held in an adult watch house.

There are also reports of children being denied access to food, blankets or seeing family members, as a disciplinary measure.

“If kids haven’t behaved well, the guards often remove their blankets or [say] that they can’t contact their family members for a period of time,” she said.

The Youth Advocacy Centre is taking legal action against the Queensland government, claiming it has failed to protect young people in watch houses.

Hayes says psychiatrists have noticed a decline in the mental health of children within the first 24 hours. Sometimes children are being held for more than 30 days.

“When kids are arrested for quite minor offences and then they’re in the youth justice system, we see an entrenchment over a period of years.”

Sam is on the repeat offender list where she lives, which means she’s targeted by Queensland’s youth crime squad, Taskforce Guardian. Credit: Queensland Police Service

In these conditions, she believes children are more likely to re-offend, and instead of having the support they need, they are leaving “angry” and “traumatised”.

“They’re not engaging in pro-social behaviours. They’re not spontaneously improving while they’re in detention.”

Queensland Youth Justice Minister Di Farmer said there was a balance between giving troubled kids the support they need and ensuring they’re not harming others.

“I make no apology for keeping the community safe. So if a young person is a risk to themselves or to the community, then they will be detained … because a court has judged that they be placed there,” she said.

“What I can tell you is that all of our intervention programs at the moment, priority is placed on our serious repeat offenders. They’re telling me about young people who they’re hooking back into education or they’re referring for mental health services or they’re making sure they have a roof over their head.”

Queensland Youth Justice Minister Di Farmer says there is a balance between giving troubled kids the support they need and ensuring they’re not harming others. Source: SBS

In response to the investigation by Guardian Australia and SBS The Feed, Queensland Police Service said in a statement that it “is aware of various allegations concerning children held in custody in QPS watchhouses”.

“Any complaints of mistreatment or inappropriate action taken within a watchhouse are treated seriously and will be subject to an investigation.”

It stated that risk assessments are undertaken when a young person is taken into custody.

“This includes considerations of the young person’s circumstances and individual needs,” the statement read. “The Human Rights of every person in custody is considered when deciding courses of action relating to violent, aggressive or harmful behaviour.”

Overrepresented and underdiagnosed

A study by youth medical research organisation the Telethon Kids Institute found that in Western Australia, four in 10 kids in detention (about 36 per cent) had FASD. Nine in 10 had some form of neurological condition.

Dr Heidi Zeeman, a neuropsychologist who specialises in diagnosing children with FASD and has worked in the Queensland justice system for two decades, says a watch house is an “inappropriate solution” for a child with FASD or a similar condition.

“FASD affects young people’s behaviour through irritability, aggression, difficulty, and self-regulating,” she said. “Not really knowing how to cope in stressful situations, not understanding the consequences of actions.”

When kids are arrested for quite minor offences and then they’re in the youth justice system, we see an entrenchment over a period of years.

Katherine Hayes, CEO of the Youth Advocacy Centre

She says putting a child in an “isolating” and “frightening” environment would only exacerbate these symptoms. Often FASD is only detected after children have reached the juvenile justice system.

“Most assessments need to involve a multidisciplinary team. It’s a multi-team approach, and often in regional and remote areas, those services aren’t available.”

Alice sees Sam, who has FASD, struggle to connect cause and effect. Those sparkly things that excited her used to come home with her, even if they didn’t belong to her and instead belonged to a friend.

“It’s every day you’ve got to really try and support her,” she said.

Alice says her granddaughter, Sam (photographed here as a young child), has struggled to connect cause and effect from a young age and says it’s a symptom of her disability. Source: Supplied

When Sam is overwhelmed, signs can come in the form of hissing sounds.

“She sort of mirrors. If you are angry at her and you’re yelling at her face, she will yell at you as well,” Alice said.

Alice says the police response has been mixed. Some are considerate of Sam’s capacity while they do their job, she says.

“Some police officers have said to me they don’t care, that they’ve been told to arrest her for everything — even though the watch house is not the right place for her.”

Alice says Sam’s mental health has deteriorated since being in the watch house, and she has noticed new self-harming behaviours, including banging her head, scratching, and biting herself.

“She could not live independently, my granddaughter, but I would like her to have a life where she doesn’t experience trauma after trauma just because she’s different from an average person.”

*Names of children and their carers have been changed due to legal restrictions on reporting on children in the justice system.

Readers seeking crisis support can contact Lifeline on 13 11 14, the Suicide Call Back Service on 1300 659 467 and Kids Helpline on 1800 55 1800 (for young people aged up to 25). More information and support with mental health is available at and on 1300 22 4636.

If you or someone you know is experiencing, or at risk of experiencing, domestic, family or sexual violence, call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit .

If you or someone you know is feeling worried or unwell, we encourage you to call 13YARN on 13 92 76 and talk with an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander Crisis Supporter.

Aboriginal Counselling Services can be contacted on 0410 539 905.