Just as Trump wants, his new Tariff advisor call for 20 percent tariffs.

Stephen Miran, the economist nominated to advise Trump, Makes the Case for 20% Tariffs.

Miran, the president-elect’s choice to chair his Council of Economic Advisers, has written that the U.S. could be better off with average tariffs of around 20% and as high as 50%, compared with the current 2%.

Miran’s views are worth studying, and not just because he’s going to advise Trump. He has described tariffs as a tool, and international intervention to weaken the dollar as another, that could address a longstanding global tension: the U.S.’s economic and military support for other countries have contributed to an overvalued dollar, wide trade deficit and hollowed-out industrial base.

“Sweeping tariffs and a shift away from strong dollar policy can have some of the broadest ramifications of any policies in decades, fundamentally reshaping the global trade and financial systems,” Miran wrote in a November report for Hudson Bay Capital, where he is senior strategist.

Miran wrote the report “A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System” before he was named in late December as Trump’s choice to chair the CEA, the White House’s in-house economic think tank.

Miran cites research by Arnaud Costinot of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Andrés Rodríguez-Clare of the University of California, Berkeley, that a tariff of around 20% is optimal, and up to 50% could still leave the U.S. better off.

An optimal tariff policy is explicitly “beggar-thy-neighbor”: one country benefits only by hurting another. Since World War II, as the world pursued reciprocal tariff reductions, “it’s hard to find real life examples of countries motivated to pursue it in a systematic, and deliberate, way,” said Doug Irwin, a trade historian at Dartmouth College.

Optimal tariff theory has some real-world drawbacks. It doesn’t seem borne out by Trump’s tariffs on China. In an interview, Costinot noted that studies found the tariffs were mostly passed through to American importers. (Miran’s report disputed those studies.)

If other countries retaliate, as China, the European Union, Mexico and Canada did in 2018, the tariff is no longer optimal: Both sides lose. “Retaliatory tariffs by other nations can nullify the welfare benefits of tariffs for the U.S.,” Miran acknowledged.

Another problem: Tariffs only leave the U.S. better off if import prices barely rise. But in that case, consumers have no incentive to switch from imported to domestic goods, which nullifies Trump’s aim of boosting American manufacturing.

Yet another caveat is that tariffs might not reduce the trade deficit because the dollar rises in response, which makes imports cheaper and exports less competitive.

As an alternative to tariffs, Miran said the U.S. could weaken the dollar through a “Mar-a-Lago Accord,” modeled on the 1985 Plaza Accord in which the U.S. and its allies jointly acted to drive down the dollar. “After a series of punitive tariffs, trading partners such as Europe and China become more receptive to some manner of currency accord in exchange for a reduction of tariffs,” he wrote. Or, the U.S. could impose a user fee on buyers of Treasury debt.

A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System

Please consider The User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System by Stephen Miran.

In this essay I attempt to catalogue some of the available tools for reshaping these systems, the tradeoffs that accompany the use of those tools, and policy options for minimizing side effects. This is not policy advocacy, but an attempt to understand the financial market consequences of potential significant changes in trade or financial policy. Tariffs provide revenue, and if offset by currency adjustments, present minimal inflationary or otherwise adverse side effects, consistent with the experience in 2018-2019. While currency offset can inhibit adjustments to trade flows, it suggests that tariffs are ultimately financed by the tariffed nation, whose real purchasing power and wealth decline, and that the revenue raised improves burden sharing for reserve asset provision.

That contradicts common sense as well as actual results but it is precisely what Trump wants to hear which is why he is headed to Trump’s Council of Economic Advisors.

During his campaign, President Trump proposed to raise tariffs to 60% on China and 10% or higher on the rest of the world, and intertwined national security with international trade. Many argue that tariffs are highly inflationary and can cause significant economic and market volatility, but that need not be the case. Indeed, the 2018-2019 tariffs, a material increase in effective rates, passed with little discernible macroeconomic consequence. The dollar rose by almost the same amount as the effective tariff rate, nullifying much of the macroeconomic impact but resulting in significant revenue. Because Chinese consumers’ purchasing power declined with their weakening currency, China effectively paid for the tariff revenue. Having just seen a major escalation in tariff rates, that experience should inform analysis of future trade conflicts.

What Really Happened

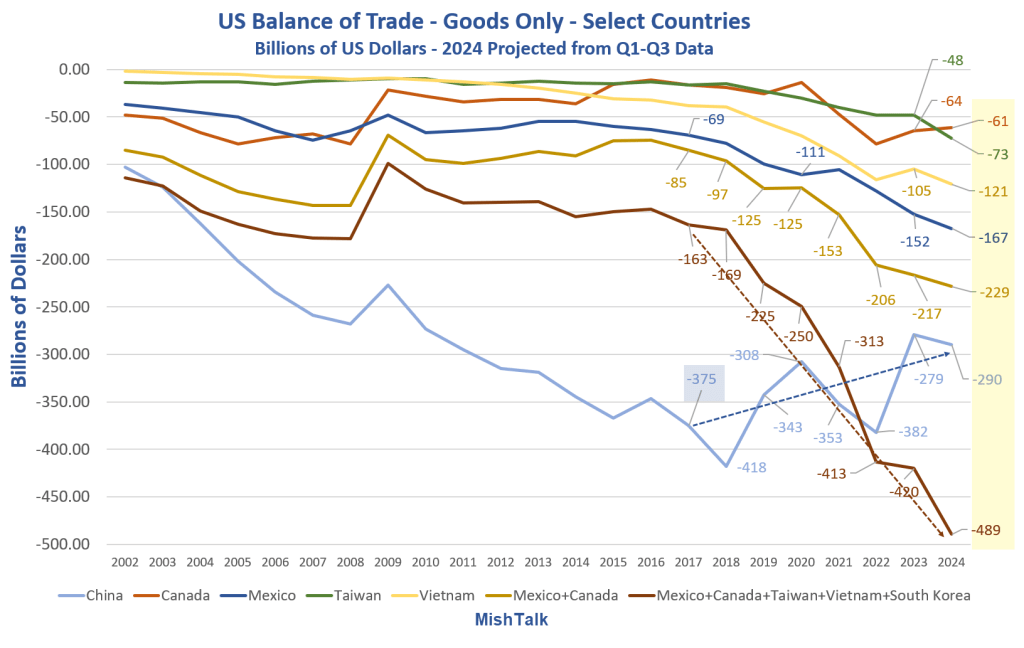

What actually happened, as the lead image clearly shows, is the trade deficit shrunk with China and rose elsewhere.

The result was not inflationary primarily because trade deficits shifted to Mexico, Canada, Vietnam, and South Korea in tax avoidance maneuvers, but also because the dollar strengthened.

Tariffs did nothing to lower the overall deficit, nothing. The overall trade deficit rose.

Roots of Discontent According to Miran

The deep unhappiness with the prevailing economic order is rooted in persistent overvaluation of the dollar and asymmetric trade conditions. Such overvaluation makes U.S. exports less competitive, U.S. imports cheaper, and handicaps American manufacturing. Manufacturing employment declines as factories close. Those local economies subside, many working families are unable to support themselves and become addicted to government handouts or opioids or move to more prosperous locations. Infrastructure declines as governments no longer service it, and housing and factories lay abandoned. Communities are “blighted.” According to Autor, Dorn and Hanson (2016), between 600,000 and one million U.S. manufacturing jobs disappeared between 2000 and 2011 due to the “China shock” of increased trade with China. Including broader categories, the jobs displaced by trade during that decade were closer to 2 million. Even 2 million job losses over a decade represents only 200,000 per year, a fraction of the churn of jobs that occurs every year because of technology, rising and falling firms and sectors, and the economic cycle. But that logic was flawed in two ways: first, the estimates of job losses due to trade increased over time as new research emerged, for instance Autor, Dorn and Hanson (2021); the “China shock” was much larger than initially estimated. Indeed, plenty of nonmanufacturing jobs which depended on local manufacturing economies were lost as well. Second, many job losses were concentrated in states and specific towns where alternative employment was not easily available. For these communities, the losses were severe.

Actual Root of Discontent

US fiscal and trade deficits soared after president Nixon ended the last semblance of the gold standard.

This allowed the US and other countries to inflate at will. Because the US had the “exorbitant privilege” of being the world’s reserve currency, other countries could and did resort to export mercantilism.

The end of gold convertibility is the one and only reason for constant trade deficits. It’s also how the US gets away with massive fiscal deficits.

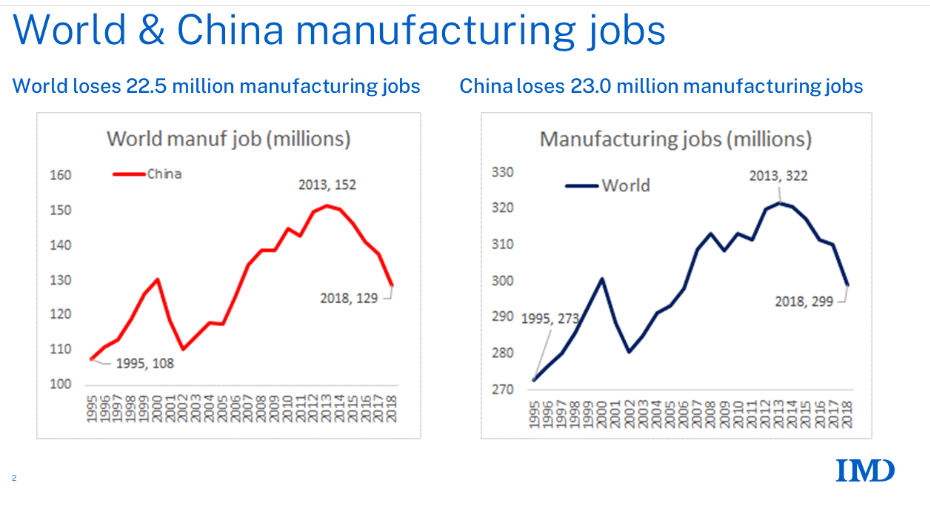

As for the loss of jobs, global manufacturing jobs are shrinking everywhere due to automation.

Rising productivity is a good thing.

Global Manufacturing Jobs

That excellent chart is from Richard Baldwin Professor of International Economics, Where in the world are manufacturing jobs going?

Global manufacturing jobs peaked in 2013. Since then, China and the total number of manufacturing jobs have declined at the same rate.

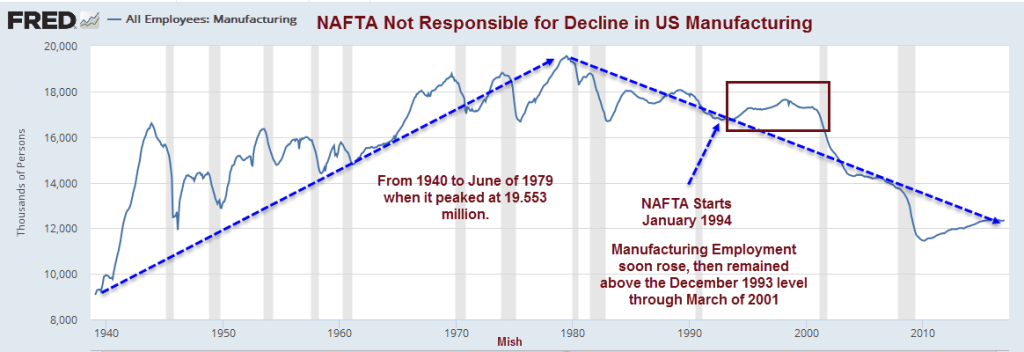

Here’s a long-term image.

Image is from Disputing Trump’s NAFTA “Catastrophe” with Pictures: What’s the True Source of Trade Imbalances?

It’s sad that Miran moans about rising productivity, but that’s what’s going on.

Burden Sharing

Despite the dollar’s role in weighing heavily on the U.S. manufacturing sector, president Trump has emphasized the value he places on its status as the global reserve currency, and threatened to punish countries that move away from the dollar. I expect this tension to be resolved by policies that aim to preserve the status of the dollar, but improve burden sharing with our trading partners.

Reflections on Burden Sharing

The EU is a basket case. So is Canada.

Precisely how is the US going to force burden sharing and what happens if countries retaliate with tariffs.

Retaliation

Where these arguments run into trouble is when other nations begin retaliating against U.S. tariffs, as China did modestly in 2018-2019. If the U.S. raises a tariff and other nations passively accept it, then it can be welfare-enhancing overall as in the optimal tariff literature.

However, retaliatory tariffs impose additional costs on America and run the risk of tit-for-tat escalations in excess of optimal tariffs that lead to a breakdown in lobal trade. Retaliatory tariffs by other nations can nullify the welfare benefits of tariffs for the U.S.

Thus, preventing retaliation will be of great importance. Because the United States is a large source of consumer demand for the world with robust capital markets, it can withstand tit-for-tat escalation more easily than other nations and is likelier to win a game of chicken.

Recall that China’s economy is dependent on capital controls keeping savings invested in increasingly inefficient allocations of capital to unproductive assets like empty apartment buildings. If tit-for-tat escalation causes increasing pressure on those capital controls for money to leave China, their economy can experience far more severe volatility than the American economy. This natural advantage limits the ability of China to respond to tariff increases.

I finally agree with Miran on something. And that is China is less able to retaliate tit-for-tat than other countries.

I also agree with Miran on capital controls and savings in unproductive assets.

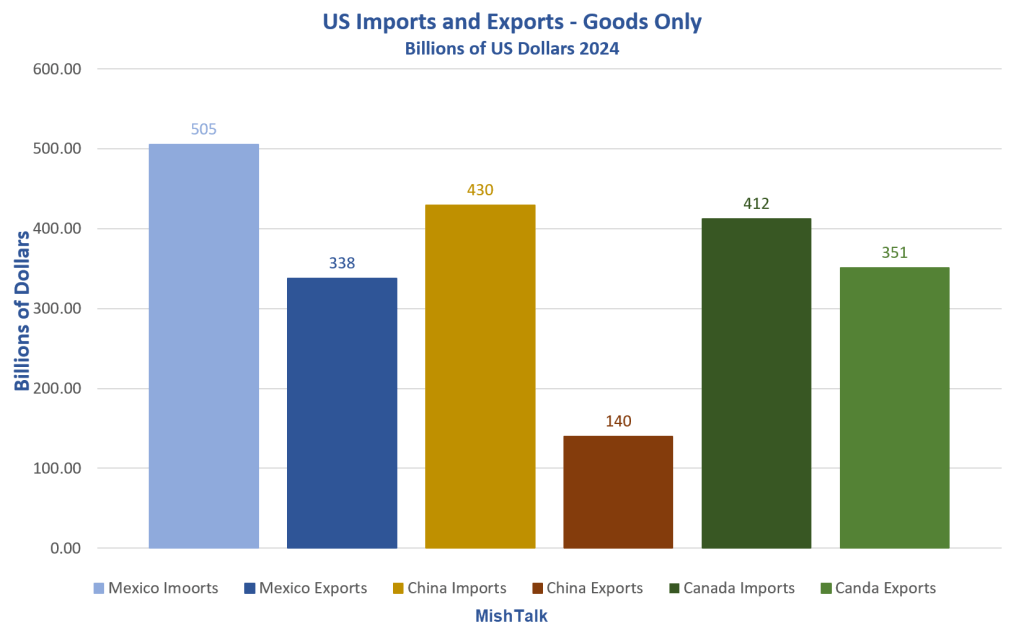

US Imports and Exports China, Canada, Mexico

Whereas China might struggle to retaliate 1-1 on Tariff hikes, Canada could easily do so and Mexico could unless Trump went totally nuts.

Also, Trump can punish China but not Mexico or Canada unless Trump wants to break the USMCA trade agreement, his own “best trade deal in history”.

USMCA is up for renegotiation in 2026. Unless he is crazy, Trump will not touch USMCA until then.

Assuming Trump is not crazy, it’s a clear bluff. So Trump can expect no concessions other than minor lip service on the border.

And upping tariffs beyond another 10 percent or so on China is not without risk.

Critical Materials Risk Assessment

Our Department of Energy has placed some of the rare earth minerals we need for weapons systems, wind turbines, batteries, semiconductors, cell phones, and aircraft on a critical materials list.

Nearly all of them are mined or refined in China.

Please consider a Critical Materials Risk Assessment by the US Department of Energy

If Trump increases tariffs on China by 60 percent, China could easily shut down rare earth exports. I have been warning about this for years

China controls more than 80% of the world’s supply of tungsten and about 90% of global magnesium production

China has an effective monopoly over processing major heavy rare earths – Dysprosium (Dy) and Terbium (Tb), and Light Rare Earths – Neodymium (Nd) and Praseodymium (Pr).

China Halts Rare Earth Exports

On December 3, I commented China Halts Rare Exports Used by US Technology Companies and the Military

This is China’s advance salvo at Trump tariffs. It comes one day after the Biden administration expanded curbs on the sale of advanced American technology to China.

It’s a powder keg.

The US gets rare earths from allies who get them from China. But don’t rule out the possibility that China shuts off all access.

If Trump gets the rest of the world to act against China, I do think China will shut off rare earths globally.

Conclusion

Trump is only interested in Yes-men. And Stephen Miran is telling Trump what Trump wants to hear. This is the only reason Trump tapped him.

My advice to Miran: “If you want to keep your job, then keep preaching nonsense.” Trump will accept nothing less.

Related Posts

January 9, 2025: Trump Demands Defense Spending 5 Percent of Europe GDP, No Chance of That

Much of the EU is struggling to get defense spending up to 2 percent of GDP. 5 percent of GDP has zero chance. Let’s discuss the math.

December 17, 2024: So, What Country Wants to Be Like Germany Now?

The collapse of Germany shocks many. But I have been discussing why this was inevitable for over a decade.

January 6, 2025: How Much Revenue Can Trump Realistically Bring in From Tariffs?

There are many moving parts to this question including Congress, retaliations, and consumer impacts.

January 8, 2025: Bonds Hammered: Is it Fed Policy, Trump Policy, or Both?

Since the Fed’s first rate cut on September 17, yields on the long end have soared. So have mortgage rates.

Trump wants to add additional items to the TCJA renewal and expand military spending too.

The bond market thinks as much of Trump’s plan as I do, and that’s why yields are rising.

If trade wars were good and easy to win, Trump would have won them in 2016. The lead chart speaks for itself.