Islam Nour has been using artificial intelligence (AI) to produce his art for some time.

The China-based designer has over 50,000 followers across social media. Recently, much of his work has focused on the ongoing conflict in Gaza.

“My goal is not to influence people as much as it is to express my feelings and shed light on the suffering in Gaza,” Nour told SBS Examines.

“I always try not to beautify the pain or minimise its extent, but to explain it as much as possible.”

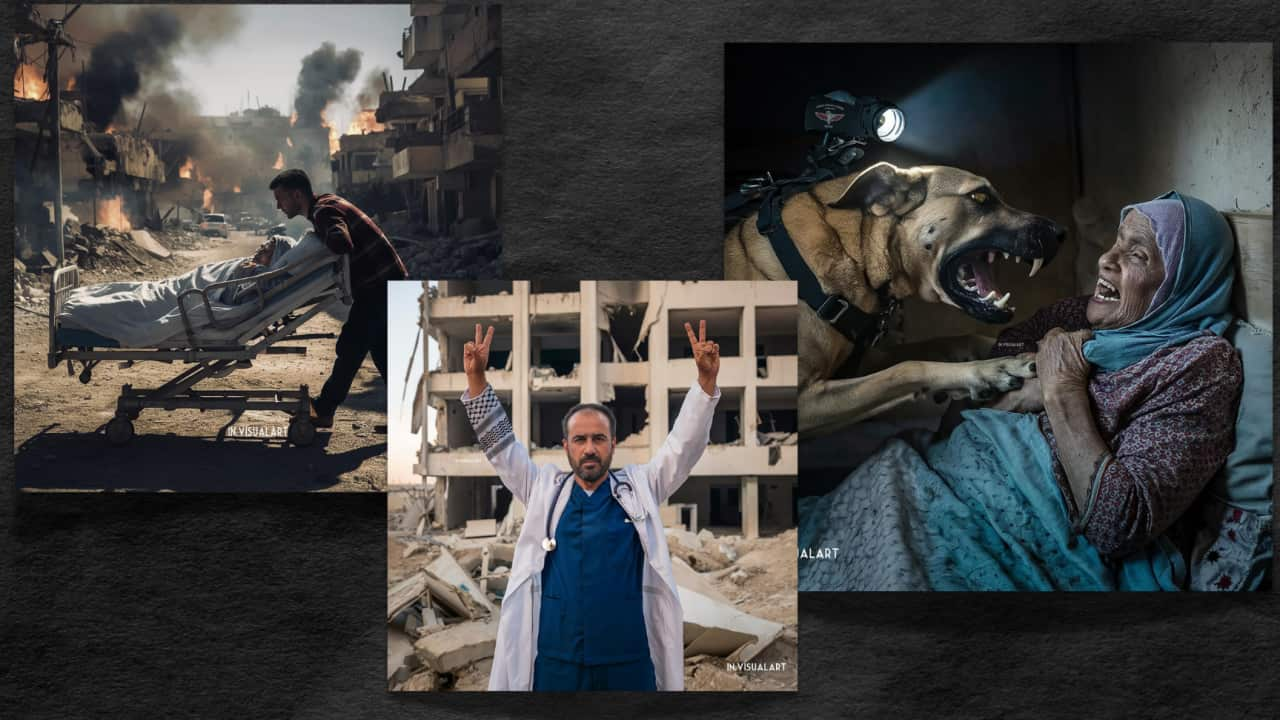

Many of Nour’s images have sparked controversy after being reposted on social media, with no acknowledgement of their AI origins.

One widely circulated image depicted the release of Dr. Mohammed Abu Selmia, a pediatrician and director of al-Shifa Hospital in Gaza.

The image was used in different contexts: either criticising the doctor’s release, or praising his return to work.

Another of Nour’s images, showing a dog lunging at an elderly woman during a military operation, reached more than a million users.

Islam Nour’s AI-generated artwork which has recently gone viral. Credit: @in.visualart

German news outlet, , has used the circumstances around Nour’s work to highlight the ethical challenge of identifying AI-generated content from real events.

“AI-generated images, no matter how deep, powerful, or expressive, cannot equal the horrific images we receive from Gaza,” Nour said.

He acknowledges his responsibility as an artist, saying he has an “ethical duty to not lie or fabricate events”.

With this in mind, he often shares real images and videos from citizens alongside his AI creations.

“It is necessary to publish the real pictures and clips,” he noted.

The creative potential for misinformation

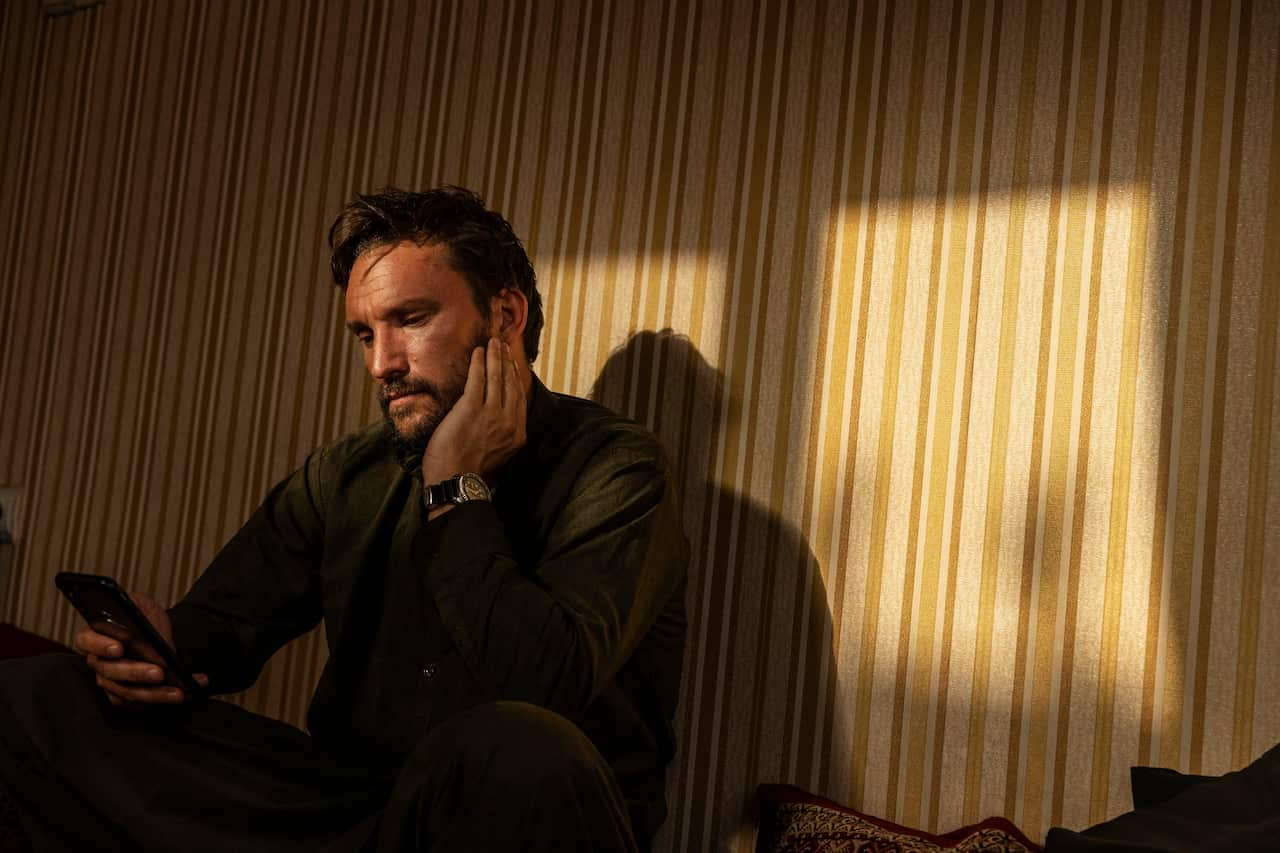

Australian photojournalist Andrew Quilty lived and worked in Afghanistan for nine years.

He believes traditional photojournalism offers a more grounded perspective.

“Documenting from the ground allows for more understanding,” explained Quilty.

He believes AI-generated images of war are dangerous territory, comparing them to “using a Disney cartoonist to depict events as serious as those in war zones”.

A self-portrait of Australian photojournalist Andrew Quilty during his time working and living in the Middle East. Credit: Andrew Quilty

Quilty said professional photojournalists are bound by ethical standards that social media creators, aren’t required to adhere to.

“A photographer relies on their good reputation… whereas there’s no enforcement to influence dissuading someone sitting on social media from generating an image that suits their narrative,” he said.

But Quilty also believes no photograph is entirely objective.

“Photographing in conflict zones doesn’t eliminate the possibility of creating bias or misinformation,” he said.

The individual ethics of AI

Associate Professor of visual communication at the University of Technology Sydney Cherine Fahd agrees objectivity is complicated.

“The idea of authenticity in a photograph is kind of fiction, because a photograph is a split-second moment in time presented from a single person’s viewpoint,” she said.

A/Prof Fahd also sees therapeutic potential for of AI images.

“AI can be used to deceive people, but it can also help us grieve,” she explained.

As AI evolves, so does the debate surrounding its impact.

While AI-generated images are not photographs in the traditional sense, they are still crafted from photos.

A/Prof Fahd doesn’t believe AI is a threat on its own.

“This idea that AI will spell our ruin — I can’t agree with that,” she said.

“What matters is that we are aware of what technology does.”