This article contains distressing content.

After an increase in complaints and allegations of human rights abuses, police have committed to a review of Queensland’s controversial watch houses.

But Katherine Hayes, the CEO of youth legal support service Youth Advocacy Centre, says vulnerable children shouldn’t be there in the first place.

“When you have a watch house that’s overflowing with adults who are often either drunk or under the influence of drugs, plus a number of young people who are heightened, it’s really difficult for watch house staff to deal with,” she said.

Katherine Hayes is a lawyer who advocates for the rights of children in the watch house. Source: SBS

Watch houses are police holding cells where people are taken into custody after being arrested. They’re designed for adults, including violent and dangerous offenders — but with youth detention centres overflowing, children as young as 11 are also held here.

Queensland Police Service (QPS) launched a review into the state’s 63 watch houses last week, admitting there are “systemic issues”.

Hayes said the review was sparked by a “significant increase in complaints” over the past 12 months.

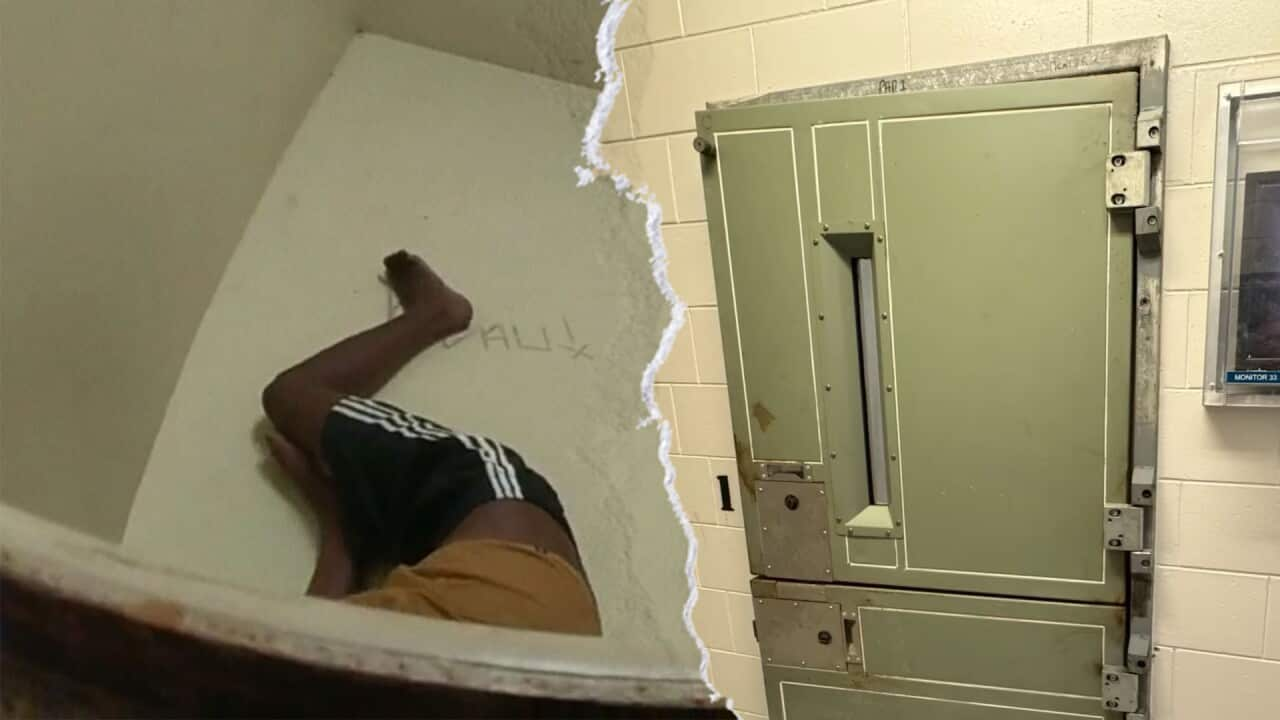

A joint investigation by The Feed and Guardian Australia revealed exclusive footage of a 13-year-old disabled Indigenous girl being placed in an isolation cell at the Cairns watch house.

Her hand was caught in the door as she tried to get out of the cell.

Another incident involved an asthmatic boy saying he was struggling to breathe in an isolation cell — he was moved there after other boys set fire to a blanket in the watch house.

An officer can be heard responding, “If you can talk, you sound like you’re breathing okay”.

Hayes said: “I think that the media coverage did help place political pressure and bring these issues to light.”

Queensland Police Commissioner Steve Gollschewski said 42 complaints involving over 100 allegations have been made so far this year.

“In some instances, our people have got it wrong,” he acknowledged.

Queensland Police Commissioner Steve Gollschewski says Queensland’s watch house system is under “significant pressure”. Source: AAP / Jono Searle

Children to continue being held in watch houses

As the review gets underway, one thing is off the table: ending the practice of holding children in the watch house.

Deputy Commissioner Cameron Harsley, who is leading the review said: “I prefer to have no children in any watch house, but unfortunately, we’re not in the position to have that.”

Hayes said government policies need to change before that happens.

“There should be no children in the watch house, but that is outside the police control,” she said.

Last year, the to allow children to be held in watch houses.

“Queensland needs alternatives to the watch houses for young people with serious mental health issues. We see a lot of young people who are put into isolation or the watch house because there’s no alternative,” Hayes said.

The Feed and Guardian Australia’s investigation showed, for the first time, what happens to children who are locked in isolation cells within watch houses. Source: Supplied

Tim Spall is a Gija man who has worked in youth mental health with First Nations young people for over 20 years. He said many children end up in the system due to mental health challenges and disengagement from education.

He said if children are locked up without proper support, there’s a strong chance they will continue to offend.

“The kid goes in, nobody acknowledges him, they just … churn him back out in community,” Spall said.

“That young person’s going to go back to exactly what he knows because there is nothing else.”

Hayes said by the time children are locked up, there has already been a government failure on multiple levels.

“The courts are under-resourced, which means that there’s high numbers of kids on remand in detention centres, which leads to the overflow into the watch house,” she said.

“A lot of these kids are Child Safety [child protection services] kids, so I feel like Child Safety hasn’t protected them in the first place.”

Queensland’s Youth Justice Minister Di Farmer said young people need to be detained if they are a danger to the community.

Di Farmer is Queensland’s Youth Justice Minister and the former Child Safety Minister. Source: AAP / Jono Searle

“I make no apologies for young people being in watch houses … we of course don’t want them in those watch houses for long periods of time,” Farmer told The Feed and Guardian Australia.

“If there are any instances of mistreatment or neglect, there’s a system in place that those things can be reported and remedied.”

What is the watch house review looking at?

According to police estimates, adults and children will spend a total of 3.8 million hours in custody this year across Queensland, an uptick of 7 per cent from last year.

They are only meant to be held in watch houses for a short period of time, but some children remain locked up for weeks on end.

“[Watch houses] are a challenging environment. What we want to do is make sure we minimise the time that people are in them,” Gollschewski said.

The watch house cells where children are kept are often small, with basic necessities such as an open toilet and mats for sleeping. Source: Supplied / Queensland Police Union

Gollschewski said the review would look at a range of areas.

“That includes all facilities, how we staff them, how we train our staff and the conduct within those watch houses and, in particular, the treatment of those in custody,” he said.

Harsley said immediate steps have also been taken.

All officers working in watch houses are now required to wear body-worn cameras, and the number of people in custody is being updated daily on the QPS website.

Footage from police body-worn cameras shows an officer restraining a 13-year-old by her neck. Source: Supplied

Hayes hopes the review will bring about real change for the 75,000 alleged offenders who pass through the state’s custody system every year.

“I’m optimistic that they are going into the review with the right approach and trying to really improve the conditions in the watch houses,” she said.

‘Tokenistic measures’: More support needed for children and First Nations people

Despite this optimism, Hayes said watch house staff need specific training on how to deal with children.

“A lot of the stories that we hear about the treatment of young people involve incidents that could have been avoided with de-escalation training or training on how to properly treat children in the watch house in the first place, such as giving them proper access to contact with their family members, appropriate food, blankets,” she said.

Tim Spall believes kids are often “written off” once they enter the youth justice system — particularly First Nations people, who make up a majority of the young people in Queensland custody.

“There’s very little, if any, support networks for them other than tokenistic measures,” he said.

Spall wants to see more mental health workers in the watch house and for them to be trained in First Nations cultural norms, such as the separation of men’s and women’s business.

“A man can ask a male those sorts of questions in a delicate way, but there’s no way he should be asking that of a female nor a female asking that of a male. That’s a big taboo in our culture,” he said.

“[Young people] need to have appropriate support that understands who they are, where they fit in, what’s happening around them, what’s happened in the community.”

Tim Spall is a youth mental health advocate who says mental health support for young people in the watch house is currently inadequate. Source: SBS

Spall said the need for support continues once children are released from the watch house.

“I’ve seen some horrendous discharge plans … kids that haven’t been to school for two years and have had huge conflict with their grandparent,” he said.

“And the discharge plan will be: ‘Return to live with grandmother and go back to school on Monday morning’.”

Police have acknowledged people in custody have increasingly complex circumstances, including those with physical and mental health needs or who are affected by drug use.

“We’ve actually got to look at making a system better for dealing with those more complex issues,” Harsley said.

Readers seeking crisis support can contact Lifeline on 13 11 14, the Suicide Call Back Service on 1300 659 467 and Kids Helpline on 1800 55 1800 (for young people aged up to 25). More information and support with mental health is available at

If you or someone you know is experiencing, or at risk of experiencing, domestic, family or sexual violence, call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit

If you or someone you know is feeling worried or unwell, we encourage you to call 13YARN on 13 92 76 and talk with an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander Crisis Supporter.

Aboriginal Counselling Services can be contacted on 0410 539 905.