Like hundreds of thousands of other Māori, Flavell has found himself increasingly called to action in recent years as the government seeks to challenge the Treaty of Waitangi, threatening 184 years of Indigenous self-determination.

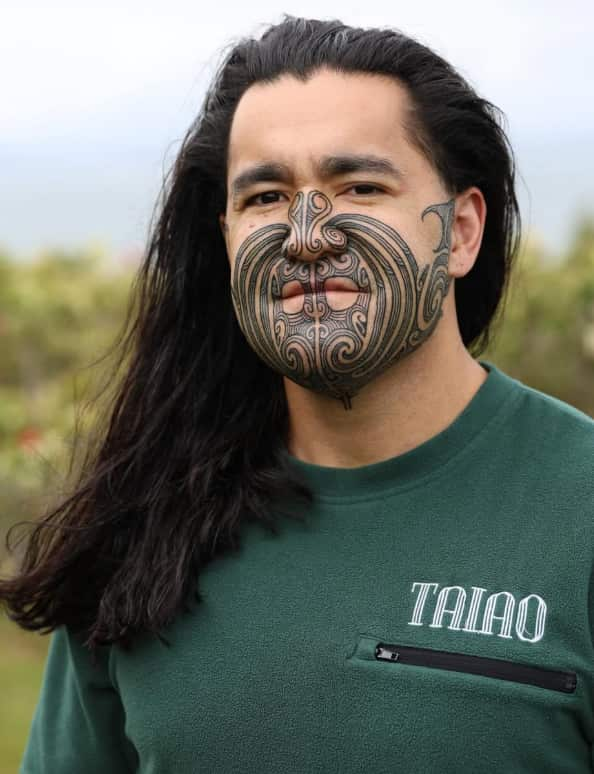

Whatanui Flavell is a Māori documentary maker who focuses on culture and politics in his work. Source: Supplied

“The politics has always been a part of my life. The culture has always been a part of my life. The language has always been a part of my life,” Flavell says.

Around 500 kilometres north of Rotorua, on the tip of New Zealand’s North Island, is the small town of Waitangi, where tens of thousands of Māori and other New Zealanders will gather for Waitangi Day on 6 February.

Whatanui Flavell says now is a “powerful time” for a generation of young Māori who are “really standing up”. Source: Supplied

The national day marks the anniversary of 40 Māori chiefs and British colonisers signing the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, which outlined the terms for their coexistence and governance.

This year, more people than ever are expected to gather in Waitangi, eclipsing last year’s 80,000, as people oppose a government bill to re-define the Treaty of Waitangi and how it is interpreted by law.

Why is the Treaty of Waitangi under threat?

The opposition has been so strong that, in January, Radio New Zealand reported a record 300,000 public submissions against it — more than double the previous record — and the parliamentary website even crashed.

Protesters calling on the New Zealand government to “honour the Treaty” at the Waitangi Treaty Grounds in Waitangi in 2024. Source: AAP / Ben McKay

Flavell grew up speaking te reo Māori (native language of the Māori people of New Zealand), which his grandparents were banned from speaking and his parents were not taught until they chose to learn it at university in the late 70s.

[My grandparents] got the Māori smacked out of them — literally if they spoke their language, they were smacked at school.

Whatanui Flavell, documentary maker

Lasting until the early 2000s, the renaissance was marked by a groundswell of youth-led action to revitalise Māori language and culture.

Among te reo speakers, 22 per cent said they could speak the language “not very well” and only 8 per cent said they could speak it “at least fairly well”.

Around 15,000 people joined a hīkoi in 2004 in Wellington to protest a government decision threatening Māori sovereignty over seabeds and foreshores. Credit: AAP

In the last two years, the government has spoken in government departments, an example of one of the more than ten “race-based policies” it has repealed, removed or reversed.

A history of peaceful hīkois

Flavell says the community’s desire and strength to “really stand up” has always been there, though it’s been somewhat dormant since 2004.

“There are many other instances where something has to be taken in order for us to come together.”

What’s at risk now?

The same week, Hana-Rāwhiti Maipi-Clarke went viral around the world for ripping up Seymour’s bill in its first reading and encouraging her colleagues to join her in a haka.

(Left to right) Debbie Ngarewa-Packer, Hana-Rāwhiti Maipi-Clarke and Eru Kapa-Kingi led a haka at the hīkoi as Māori communities marched to protect and advocate for the interpretation of the Treaty of Waitangi and Māori rights in 2024. Source: Getty / Joe Allison

New Zealand’s youngest MP since 1853, 22-year-old Maipi-Clarke was one of the main speakers at November’s hīkoi.

“That momentum has been built up over a number of years and really was a convergence of Māori who were ready for and believe in a future of Māori independence and are sick of a reality where we are continually and consistently treated as second-class citizens on our own land by successive governments.”

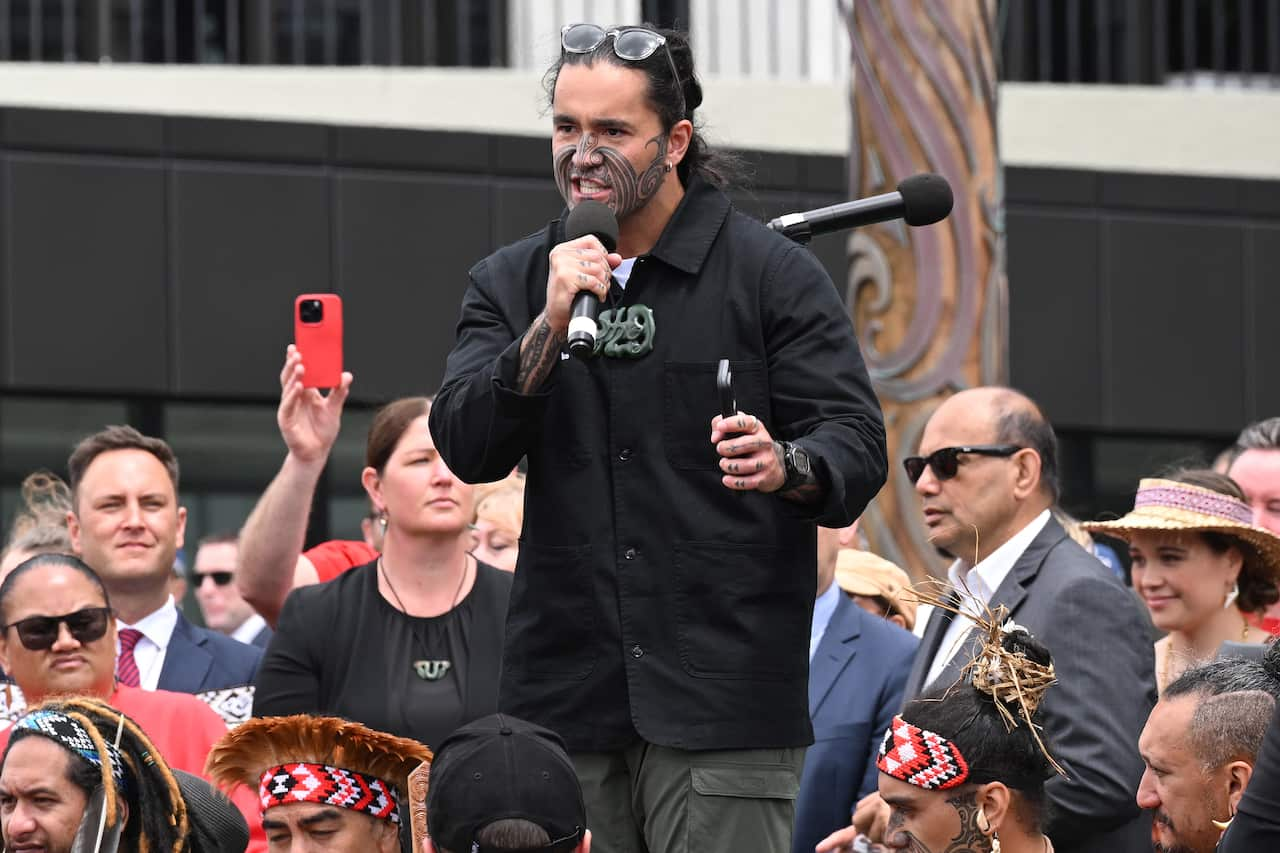

Eru Kapa-Kingi is a Māori organiser who says the government is “one of the worst we’ve seen” with respect to upholding the Treaty of Waitangi. Source: Supplied

Kapa-Kingi says the government is “amongst the worst we’ve seen in respect to the Treaty”.

He says that growing up, it wasn’t “cool or easy to be Māori”, but there’s been a shift in the last decade thanks to a “new generation of thinking” that doesn’t “bow to a system that wasn’t made for us”.

“It’s no coincidence. It’s I think a direct result of us, the reclamation generation really coming into its own,” Kapa-Kingi says.

It’s becoming more normalised and also more accepted amongst ourselves to be Māori, to embrace our culture and to embrace our power as tangata whenua [original inhabitants].

Eru Kapa-Kingi, a Māori organiser and academic

Kapa-Kingi says last year’s Waitangi gatherings were “humongous” and this year will be even bigger.

Eru Kapa-Kingi says Waitangi Day is a time to reflect. Source: Getty / Joe Allison

But Kapa-Kingi says the day is not a holiday and should be a time to reflect.

“That’s why it’s important to have forward-looking, onward-moving discussions at Waitangi around how we make that a reality.”

‘Hard conversations’

“These are hard conversations to have with a government that doesn’t want to have them,” she says.

Te Aomihia Walker is a Gisborne-based activist and environmental consultant. Source: Supplied

Walker recalls learning about Black civil rights in the United States and the British monarchy when she was at school, but the history of the Treaty wasn’t taught.

She says people need to understand that the Treaty didn’t give Māori people rights, adding that “those rights were pre-existing before the British got here”.

Walker says this is “really worrying”, but she can see that “with chaos and crisis comes opportunity”.

If anything, it’s enabled us to come together a bit more as Māori as well as with our other Indigenous brothers and sisters from the Pacific and across the world as well as allies.

Te Aomihia Walker, Māori youth activist

“Everyone’s kind of seeing that we are just going backwards and it’s just removing 40 years of hard work of people trying to integrate more Treaty rights policy into legislation.”