Key Points

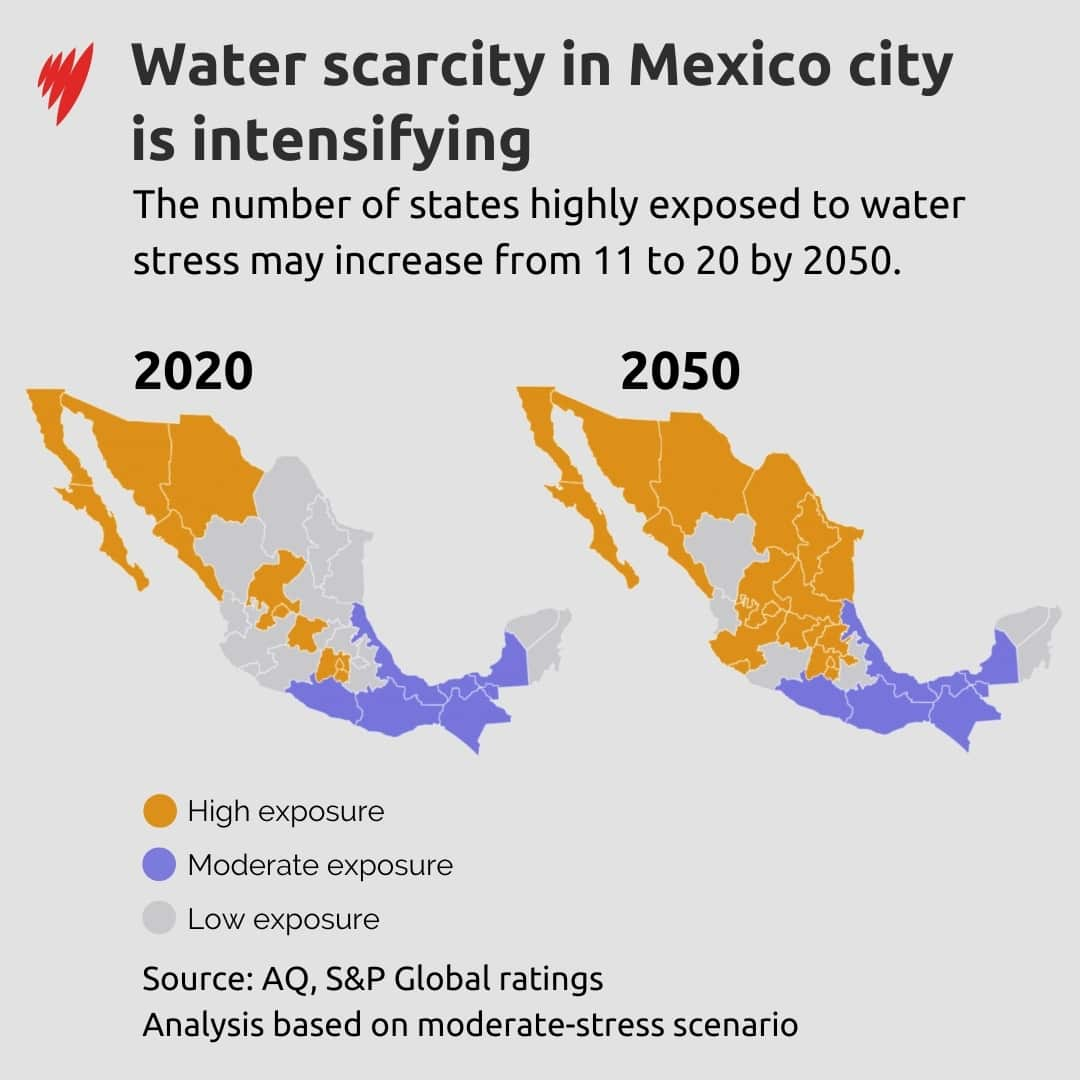

- Water reservoirs in Mexico City hit historic lows this month, and some experts fear the taps could run dry in June.

- The shortage is the result of severe drought and heat, as well as structural issues making it hard to capture water.

- The societal impacts could be profound, and range from public health through to employment and tourism.

In North America’s most populous city, the taps could run dry within weeks.

Water reservoirs in Mexico City hit historic lows this month amid ongoing drought conditions and one of the most extreme heat waves the country has ever faced.

The Cutzamala water system — one of the world’s largest networks of dams, canals and pipes that supplies more than a quarter of the city’s water — is at 30 per cent of its normal capacity, an 8 per cent drop compared to the same time last year and a 15 per cent drop compared to the year before.

The underground aquifers that supply a further 60 per cent of the city’s water, meanwhile, are over-extracted, with groundwater being pumped out twice as fast as it is replenished.

If it doesn’t rain soon, experts fear Day Zero — when the Cutzamala system’s levels deplete to such a level that it can no longer adequately supply Mexico City’s 22.5 million residents with water — could happen as soon as June.

How did this happen?

The Mexican capital’s water woes are the result of several compounding factors — climatic, structural and systemic.

For one, Mexico is facing the twin challenges of a long drought and searing heat wave, the latter of which has caused at least 48 deaths from heat stroke and dehydration in two months. These two factors, the effects of which are particularly severe due to climate change, are amplifying the problem not only through a lack of rainfall but also excessive evaporation and drying.

This has been a factor for some time. When asked in February whether Mexico was facing a water crisis, Dr Roberto Constantino Toto, the general coordinator of the Water Research Network, told reporters “no doubt about it, there are evident signs. But I need to say this is nothing new. This is a crisis that has been taking shape throughout many years and which now has reached a certain stability.”

“Most of the water we consume comes from the rain cycle,” Toto added. “And as the natural process that we call global environmental change takes place, the regularity and intensity of rainfall in an important part of our territory is affected, and a lack of availability is generated”.

Yet as Quentin Grafton, an economist at Australian National University’s Corporate School of Public Policy, whose work has focused on water allocation, justice and scarcity, explained, it isn’t just dry conditions that lead cities to face water crises of this scale.

“It’s not just an issue around the drought or insufficient rainfall for a sufficiently long enough period of time,” Grafton told SBS News.

“Cities run out of water when they haven’t planned for the water that they’ve got. And that could be in terms of the dams that they’ve used for trapping and capturing water, or it could be a groundwater issue.”

In Mexico City’s case, the groundwater issue has long been exacerbated by structural issues. The sprawling city, built in the 14th century by Spanish colonisers, who built it on top of a drained lake, is mostly comprised of hard, sealed surfaces that don’t allow rainfall to permeate through to the aquifers.

In addition, much of the water that does enter the city’s supply flows along a 12,800km-long grid through old pipes that are susceptible to leaks.

According to Mexico’s federal district water operator, SACMEX, nearly 40 per cent of Mexico City’s water is lost in transit due to these leaky pipes.

Mexico is facing the twin challenges of a long drought and searing heat wave, the effects of which have been particularly severe due to climate change. Credit: EPA

Repairing the pipes would dramatically reduce the amount of wastage but would likely cost billions of dollars. Now, as the country gears up for elections, the water issue is becoming a key political issue, with contenders promising to address the spiralling crisis while defending their handling of it to date.

Grafton, however, suggested that it’s often a lack of planning and forward thinking that gets cities into these situations in the first place.

“There’s generally a series of screw-ups to get you to that point, because a city the size of Mexico City shouldn’t be in that situation at all,” he said. “Running out of water for a supersized city should never happen.”

What are the impacts?

The effects of a city running out of water are many and complicated, and extend beyond people going thirsty.

In 2018, Cape Town in South Africa narrowly avoided reaching Day Zero after a one-in-400-year drought drove the city into a severe water crisis.

“Even in extreme cases of the big cities like Cape Town, there was enough drinking water,” Grafton explained. “What they mean when they say ‘we’re running out of water’ is there’s not enough water to meet all the demands.”

Failure to meet these demands can affect cities and communities in a variety of ways, ranging from public health through to employment and tourism.

What typically happens when a city reaches a crisis point, Grafton explained, is that the water supply gets switched off.

“So the water coming out of your tap doesn’t come out of your tap anymore — or if it does, it only comes out one hour a day,” he said.

“Once you start to do that, you can get all sorts of nasties in the water because it’s not flowing, it’s in the pipe system for a long enough period of time, there’s issues around disinfection — so there’s public health issues.”

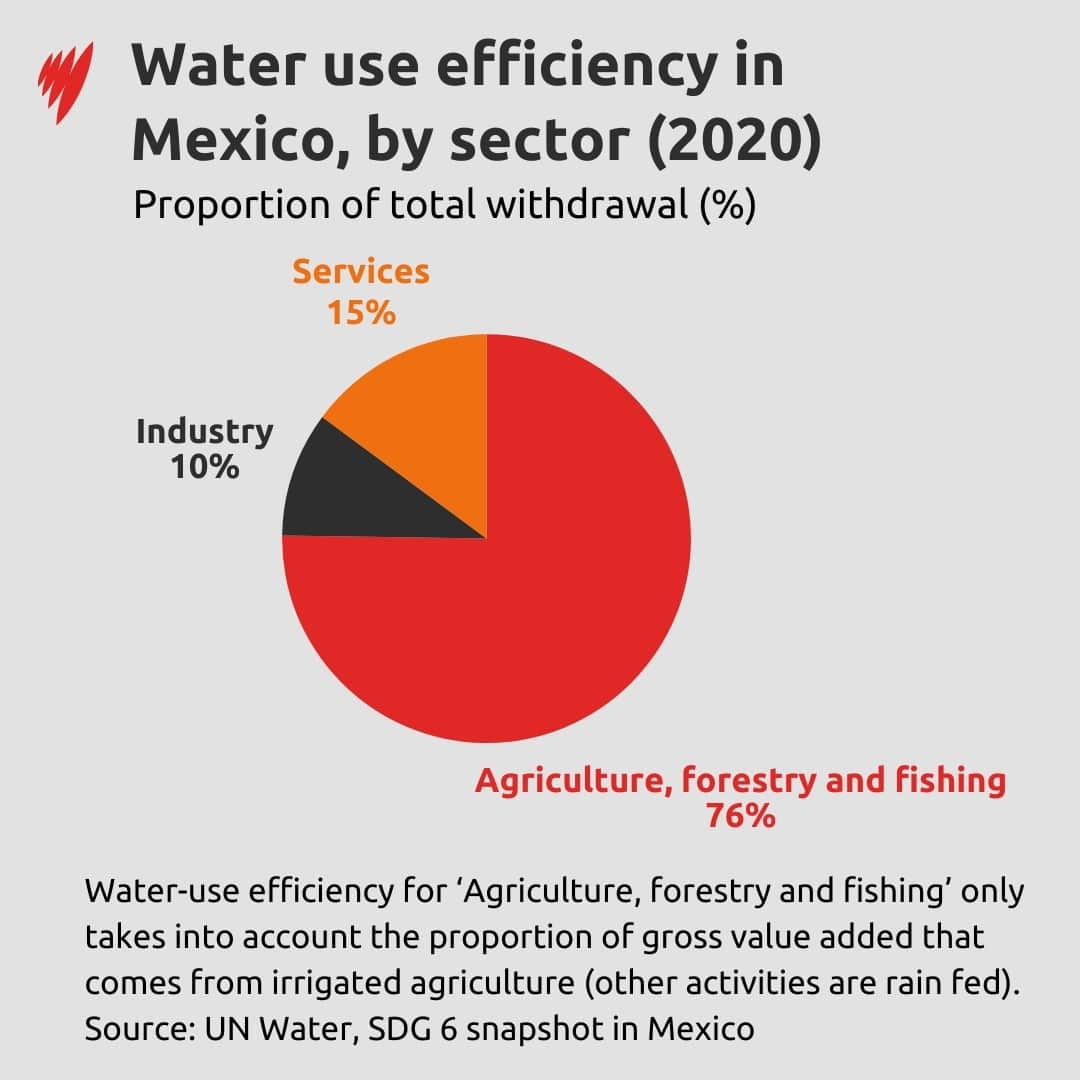

Grafton also pointed to “a whole series of industries that are highly, heavily dependent on water, whether that be agriculture, tourism or that just bottling of beer or Coca-Cola”.

Agriculture, forestry and fishing are the industries that rely most on water extraction. As Grafton pointed out, though, “most industries use water in some form or other – whether it’s providing it as a cleaning or as an actually input into the process — so those industries basically have to suspend activity [in the event of a water crisis].”

“They just can’t operate, so that means people become unemployed.”

Impacts of running out of water are unevenly distributed

These are the compounding calamities that Mexico City is now edging towards. Nor are such impacts evenly distributed. Rather, they are delineated along socioeconomic lines.

In South Africa, one of the world’s most unequal countries, Cape Town’s wealthy were better placed to weather the water crisis in a variety of ways, whether by buying truckloads of bottled water or hiring companies to dig boreholes and wells.

Less advantaged people had to rely on the government to solve the crisis or supply clean water, while trying to survive day to day.

“Inequity plays out in water very obviously,” Giulio Boccaletti, global managing director for water with non-profit The Nature Conservancy told The Washington Post in 2018. “The social contract breaks down, if the rich find their own solution and leave the rest to fend for themselves.”

Grafton made a similar point.

“It’s typically the impoverished who get less access in these situations,” he said.

“If you’re in Cape Town and you’re impoverished — and there’s lots of people in Cape Town who are in that situation, and that’d be true in Mexico City — you’re going to have to rely on some sort of supply from some source to allow you to be able to access the drinking water. The taps are closed. But if you’re well off, it’s not a problem to go and buy a lot of bottled water.”

“The impact tends to be worse on those who are less well off.”