While many Bhutanese community members will enjoy an audience with the monarch, Lhotshampa refugees say they have been denied such access.

A statement from the Royal Bhutanese Embassy on King Jigme Khesar’s visit to Australia. Credit: Facebook/Royal Bhutanese Embassy

King Jigme Khesar, the fifth of the Wangchuk dynasty to rule the Himalayan nation between India and China, ascended the throne after his father, King Jigme Singye Wangchuk, abdicated in 2006.

Diplomatic ties between Australia and Bhutan formally began in September 2002, and Bhutan opened an embassy in Canberra in 2022 — only the country’s sixth globally.

Diplomatic ties between Australia and Bhutan formally began in September 2002, decades after the Bhutanese government was invited to attend the Colombo Plan meeting in Melbourne in 1962. Source: iStockphoto / sezer ozger/Getty Images/iStockphoto

Some observers told SBS Nepali they view the visit as an effort to seek investment, as the Himalayan country toys with the idea of developing a ‘mindfulness city’ on its tropical southern border with India.

In a national day address in December last year, the King said this project was to enable Bhutanese living overseas to return.

Bhutanese community in Australia

But, for many of the 6,000-plus Lhotshampa refugees in Australia, the royal visit holds different significance compared to others in the Bhutanese community who are studying here or have migrated under the Skilled-Visa scheme.

After spending almost two decades in UNHCR-managed camps, many now call countries like Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the US home following a resettlement process that began in 2008.

Concern for relatives

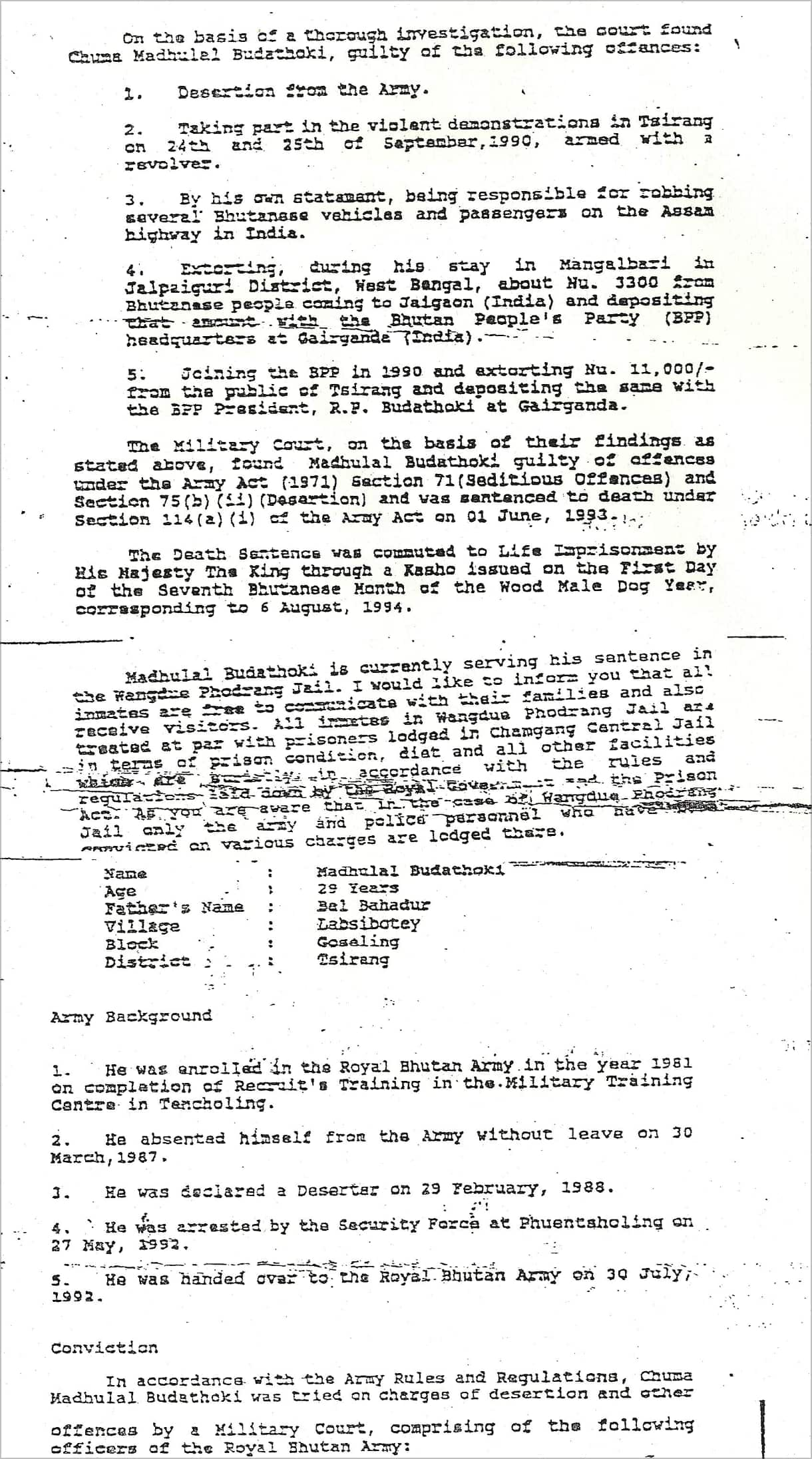

“It was during this time, some people from the community enticed him to join the Bhutan Peoples’ Party (BPP) and be a commander of Chirang district for the people’s movement. That’s why he was targeted.”

A copy of the document showing charges laid against Madhulal Budathoki. Credit: Supplied by Pasru Budathoki

According to Budathoki, his half-brother was arrested after attending a mass protest event.

Budathoki said he eventually learnt about the arrest of his half-brother from a local radio broadcast.

Bal Bahadur Budathoki and his wife Kamala. Credit: Supplied by Parsu Budathoki

Madhulal was originally sentenced to death, but the then King Jigme Singye, or ‘K4’ as he is commonly known, reduced the severity to life-imprisonment.

“My ailing parents who are in Australia, have only one wish — to see Madhulal before they die,” Budathoki said.

‘Political prisoners’ still in incarceration

Harimaya Rai said her brother was jailed for treason and being a revolutionary fighter.

Bhutanese refugees cycle past a police checkpost at the entrance to the Beldangi II Refugee Camp, some 300km south-east of Kathmandu on 7 October, 2009. Source: AFP / PRAKASH MATHEMA/AFP via Getty Images

She and her father were allowed to go to Bhutan and meet their jailed family member through International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) facilitation before their resettlement in Australia.

Kumar Gautam’s family is now divided between Canada and Australia, while he has been imprisoned in Bhutan since early 2008.

Mother Ran Maya Gautam (L), Kumar Gautam (M) and his father Bhagirath Gautam (R). Credit: Supplied by Dadhi Adhikari

His brother-in-law Dadhi Adhikari, who lives in Melbourne, said the health of Gautam’s mother, Ran Maya Gautam, is deteriorating as she awaits news.

“She looks lost with tears constantly in her eyes. She just wants to see her son,” Adhikari said.

If we were to meet the King, we would request him to provide amnesty to Kumar and all other political prisoners.

Dadhi Adhikari

All the families who spoke to SBS Nepali said they welcomed the current King’s “modernising approach”, but felt their human rights were being violated by them being denied entry to Bhutan.

By being denied entry to Bhutan, Lhotshampa refugees say their human rights are being violated. Credit: Eric Lafforgue/Art in All of Us/Corbis via Getty Images

Tila Guragain is the head of the Bhutanese Community in Australia Inc, a community organisation formed by Bhutanese exiles living in Victoria.

“There are political prisoners in Bhutanese jails. We want them to be released,” Guragain said.

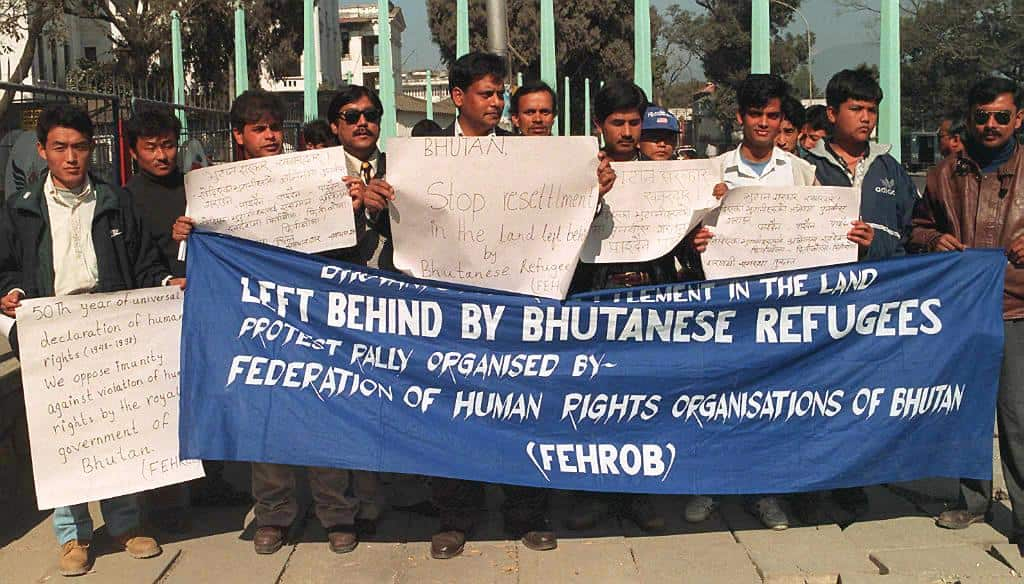

A group of Bhutanese refugees protest in Kathmandu on 15 January, 1998. The demonstrators were protesting against the Bhutan government’s action of distributing land left behind by the evicted Lhotshampa refugees. Source: AFP / DEVENDRA MAN SINGH/AFP via Getty Images

“Also, despite us being Australian citizens, we are barred from entering Bhutan. Other Australian citizens can enter but we, from the refugee background, can’t, which we claim to be discrimination against the Australian people and government.

“And there are over 6,000 people still in Nepali (refugee) camps who would like to resettle.”

‘Locked out’

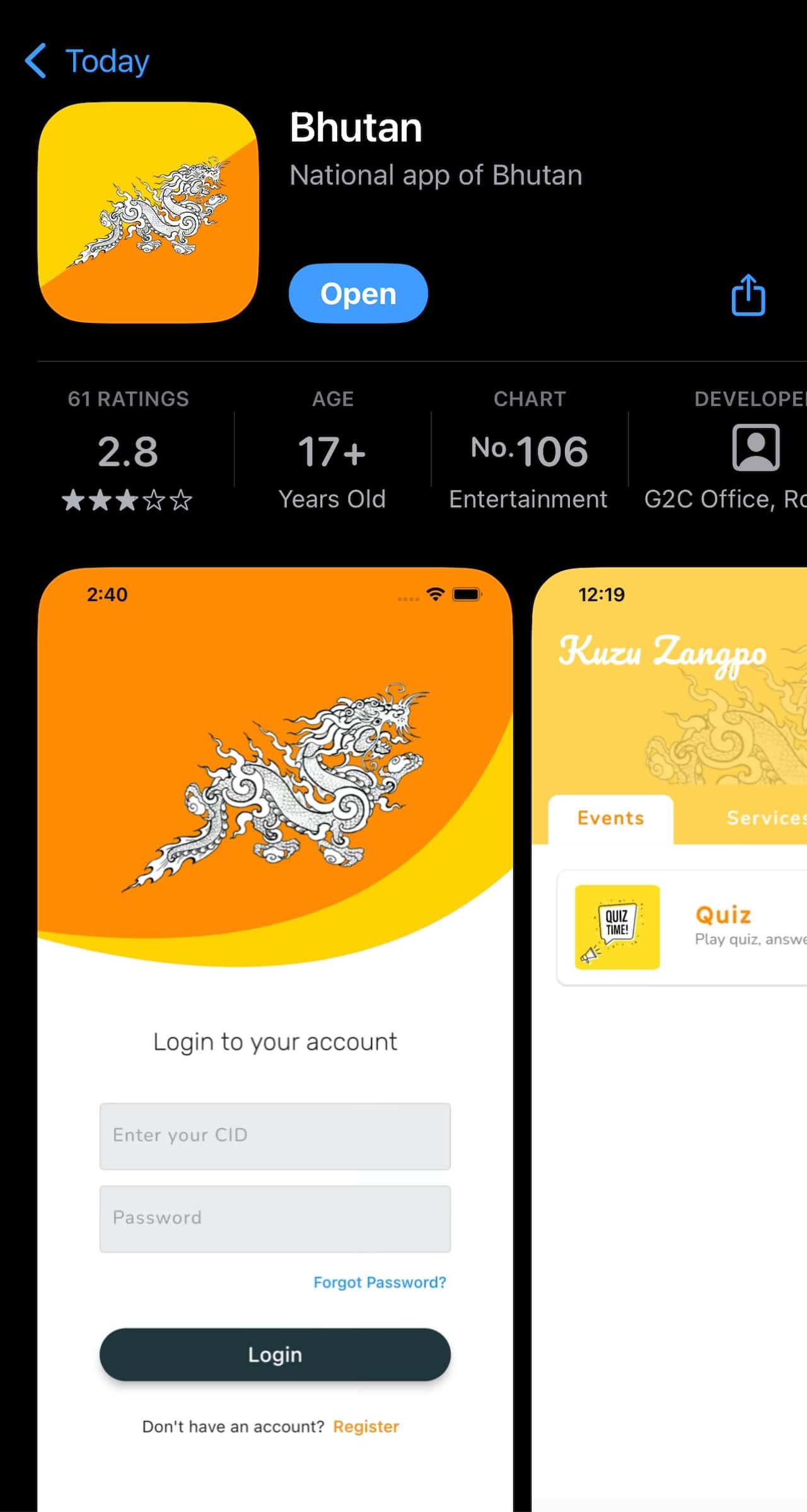

“But one needs to scan (official) documents such as citizenship (certificate of Bhutan) first to be eligible for registration. We don’t have (Bhutanese) citizenship so we may not get an opportunity for the meet.”

The Bhutan government’s app which is required for requesting an audience with the monarch. Credit: SBS Nepali

SBS Nepali contacted the Royal Bhutanese Embassy in Canberra but did not receive a comment on the registration process or other concerns raised by the Lhotshampa community.

But Dhungel said the King must solve “irritants” like the refugee matter, “otherwise, the human rights issues and the agenda of political prisoners will follow the government and the King wherever they go in the world.”.

“From our recent surveys, about half have indicated that they will be willing to take on the offer of third-country resettlement if offered,” he said.

Om Dhungel considers himself lucky to have a new life in Australia. Source: Supplied

“This leaves about 3,000 people who Bhutan will have to take back. And Bhutan does not need spend a penny for the resettlement as there are countries which are ready to fund this.”

Dhungel said the matter “should not be prolonged into an inter-generational issue”.

Rather than passing the anger, hatred and sense of revenge to our new generation, we need to pass on our learnings. This is the message we want to convey to the King during his visit.

Om Dhungel

“While I cannot say that everyone from the refugee background will be happy with the King’s visit, what I can say is the majority of people are welcoming because he’s a persona with very dynamic leadership (qualities),” he said.

Since Bhutan and Australia have people-to-people connection, government-to-government connection and family-to-family connection, the visit is a good thing (to have happened).

Parsuram Sharma-Luital

“There are different kinds of advocacy, human rights advocacy, protest advocacy. But with Bhutan, (there’s) only one thing that’s going to work, positive diplomacy.”

Personal connection

“During the 1997 Dashain (a major Nepali festival), I had the opportunity to be blessed by the King. I was one of 35 Nepali (speakers) who were invited to the palace. The present King was seated on my right and I had an opportunity to have a luncheon and three hours with him. I again met him when I was working as a district agriculture officer,” he said.

The fact he (King Jigme Khesar) will be here during Dashain is wonderful.

Parsuram Sharma-Luital

“They say timing is everything in politics, I believe that time will come for us to be able to visit our birthplace,” he said.

Parsuram Sharma-Luital shared his memories of the Bhutanese monarch. Credit: SBS Nepali

“Our ancestry is our ancestry. That identity cannot be taken (away) by anything, including people who had to leave Bhutan, (and) stay in (refugee) camps.”

*SBS Nepali contacted the Royal Bhutanese Embassy for comment, but did not receive a response by the time of publication.