This article contains references to domestic violence.

As 2024 comes to a close, women’s safety advocates will remember the year as one of the worst on record.

Despite rallies and demonstrations, calls for action, increased national interest, and new , the number of women killed in gender-based violence has increased.

Throughout the year, violence has impacted women from a variety of backgrounds across a wide range of ages and different parts of the country. Some have made national and international headlines, while others have gone widely unreported.

All are part of a national crisis.

Is violence against women in Australia getting worse?

At the time of writing, there have been 78 women killed this year due to gender-based violence, according to advocacy group Destroy the Joint’s project .

In 2023, this figure stood at 64.

In 2022, the organisation tracked 56 deaths, up from 44 in 2021 and 62 in 2020.

“It’s heartbreaking for us volunteers, and it’s heartbreaking for the families and friends of the women who have been killed,” said Counting Dead Women volunteer Dr Jill Tomlinson.

“We do the count so that we can honour the women and also measure the deaths of the women who die by violence, because by counting them, we hope to raise awareness of the problem of DV (domestic violence) and family violence and bring greater resources to resolve the problem.”

Australian Femicide Watch, which is run by researcher and , keeps track of female victims of violence, including Australians who have died overseas.

According to their tally, 101 Australian women have been killed this year at the time of writing, up from 74 in 2023.

The number of women seeking help is also dangerously high, with many frontline services at capacity.

Karen Bevan, CEO of Full Stop Australia, an organisation supporting people who experience sexual, family or domestic violence, said services are experiencing “enormous surges” in demand across the country.

“Domestic and family violence services are reporting that demand has increased this year; crisis and emergency refuge services have been shouting out all year about the challenges they’re facing in meeting need,” she said.

“Our own service, 1800 FULL STOP — which is an unfunded national trauma counselling service for people subject to domestic family and sexual violence — has hit levels of demand that we have not seen before.”

Neesha Eckersley, acting CEO of Women’s Community Shelters, an organisation that works with communities to set up crisis accommodation, said it had been an “incredibly demanding” year.

“We’ve seen unprecedented demand across our growing shelter network. Many shelters have consistently operated at capacity, and unfortunately, this has meant turning away women and children seeking safety due to limited space,” she said.

“The crises in housing supply, housing affordability, and the rising cost of living, alongside an increase in domestic violence-related homicides, have made the situation even more urgent.”

How does Australia compare to the rest of the world?

Gauging data and comparisons at a global level is complex due to different reporting systems and data delays.

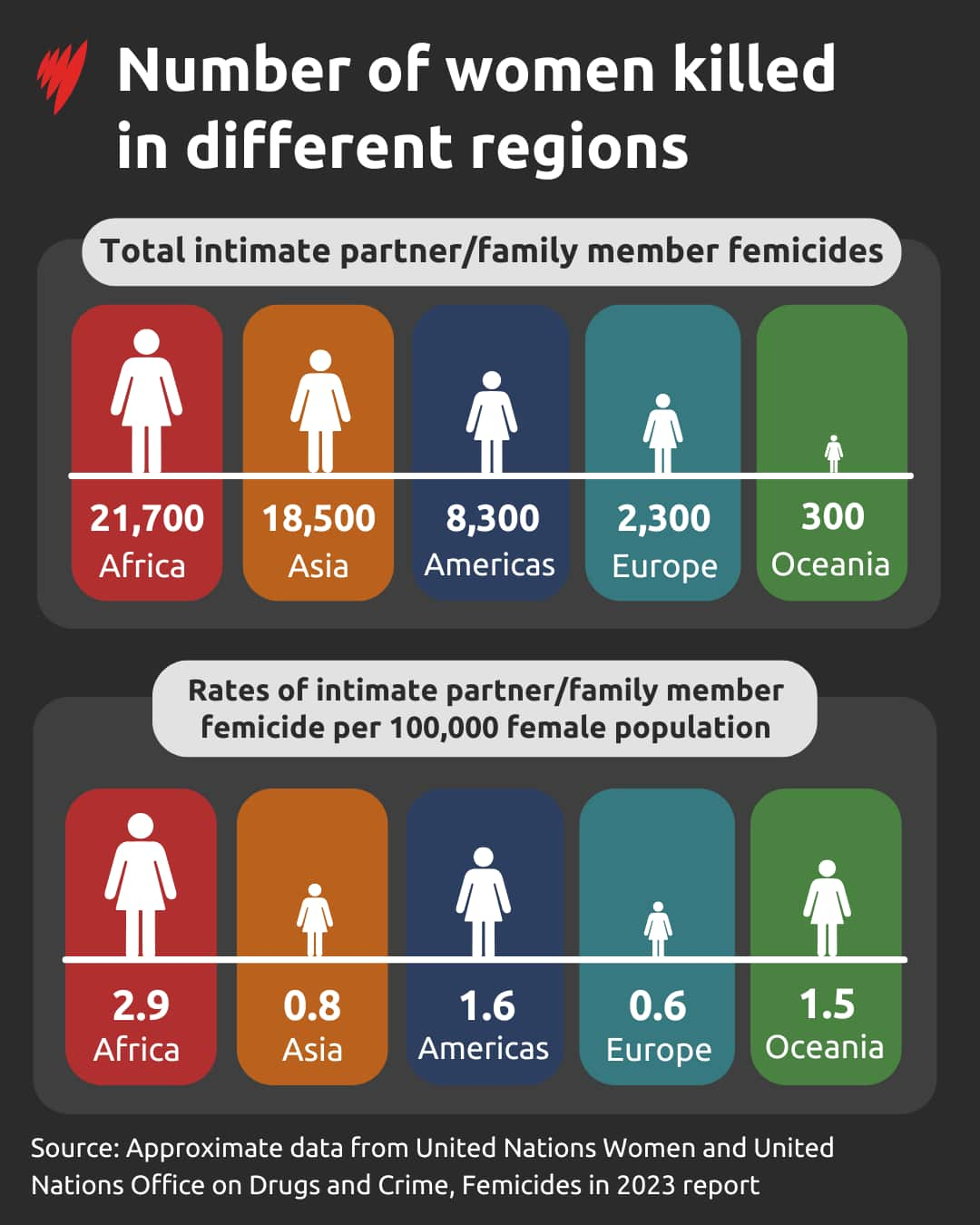

According to ‘Femicides in 2023’, the latest report from United Nations Women and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, approximately 51,100 women and girls were killed by their intimate partners or other family members last year.

The report categorised Africa as the region with the highest prevalence of women killed in violence, with and estimated 21,700 femicides in 2023. According to the UN, this is equivalent to 2.9 per 100,000 female population.

Oceania (which includes Australia) had an estimated 300 that year, equivalent to 1.5 deaths per 100,000 women.

Who is most vulnerable to domestic violence?

Rasha Abbas is CEO of inTouch, a specialist family violence organisation that supports migrant and refugee women in accordance with their culture and language.

She said family violence happens across all cultures, communities and socioeconomic levels, but the women inTouch supports are particularly vulnerable.

“They’re often on a temporary visa, there are language barriers, there are cultural barriers, social isolation, no financial wellbeing, they’re at the highest risk of homelessness … the intersectionality of what they’re facing just makes them more vulnerable,” she said.

“And the other problem for us is they often don’t even know that (what they’re experiencing) is actually even family violence and that it’s against the law.”

Abbas said cultural factors can often add a level of complexity for migrant or refugee women experiencing violence in relationships.

She said many women also do not know of the support services available to them or are afraid of going to the police or through the legal system, particularly if there are language barriers.

“We do need to make sure that they are not left behind and that the complexity of the situation they’re dealing with is taken into consideration and that we do better to support them,” she said.

“And we (inTouch) definitely don’t have enough support, we turn away a significant number of cases — we are at capacity, but also we know that mainstream services often are not able to support those women.”

Indigenous women are disproportionately impacted by gender-based violence. Source: AAP / Steve Markham

Patty Kinnersly, CEO of anti-violence organisation Our Watch, said Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are also by gender-based violence.

“It is our national shame that since June, 12 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women have been reportedly killed by men’s violence. This has received little media attention, or the public outcry that these women and their families deserve,” she said.

“Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are eight times more likely to be killed by homicide and 31 times more likely to be hospitalised as a result of violence.”

‘We need to continue the work we have started’

The federal government $4 billion into women’s safety across the four domains of the National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022-2032 across its three budgets.

This includes 113 individual initiatives to address prevention, early intervention, response, healing and recovery. In 2024, the government also held two dedicated National Cabinets on women’s safety and made the Leaving Violence Program permanent.

Social Services Minister Amanda Rishworth said the federal government, along with state and territory governments, remains committed to ending gender-based violence in one generation.

She said she had thought about the issue “every day” since taking on the portfolio.

“Ending violence against women and children is everyone’s responsibility. We all need to continue the work we have started and work together towards progress,” she said.

Tomlinson said the fact that the number of deaths had increased despite support and resources illustrated the complexity of the issue.

“We need consistent attention, we need support for women experiencing family violence … there are lots of factors that we need and we need them all to be working together so that we can see that reduction in the numbers.”

Kinnersly said underlying causes of violence including gender stereotypes, sexism and disrespect also need to be addressed in order to change the story.

“The sad reality is that while some men continue to hold unequal, disrespectful, racist, homophobic or ableist views, women in this country are not safe,” she said.

“We must continue to channel our anger and grief to action — in our homes, workplaces, sporting clubs, schools and within government.”

If you or someone you know is impacted by family and domestic violence, call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732, text 0458 737 732, or visit . In an emergency, call 000.

, operated by No to Violence, can be contacted on 1300 766 491.