In 2022, Leo’s* hot pot restaurant in China’s Hunan province was forced to close, leaving him with a debt of over 100,000 yuan ($20,000).

To make his repayments, he set his sights on Australia after watching videos on YouTube, which described the country as a “paradise for blue-collar workers”.

“I saw a couple of cases in the videos that said they get between $1,500 to $1,800 per week in Australia,” he said.

“I calculated that I’d be able to pay off my debt in six months working on a construction site in Australia.”

With the assistance of a China-based migration agent who charged a $2,000 service fee, he applied for an Australian student visa and was successful, enrolling in a Vocational Education and Training (VET) course at a Sydney college.

Upon arriving in Sydney in November 2022, instead of attending classes, Leo worked more than 10 hours a day on a construction site, in breach of his visa, which from 1 July 2023 limits holders to working no more than 48 hours per fortnight during the course of their studies.

Leo* said he had worked around a dozen cash-in-hand jobs within a year of arriving in Australia. Source: Supplied / Leo*

The videos he saw were posted on the YouTube profile of a China-based, self-identifying migration agent who promotes a “half-work and half-study” program in Australia to potential clients.

The channel features videos and interviews with successful visa applicants, who detail the application process and benefits of “higher wages” in Australia.

It is among dozens of channels and profiles seen by SBS Chinese predominantly on Chinese social media platforms such as WeChat and Douyin — China’s equivalent to TikTok — where individuals provide migration advice and offer services to apply for Australian visas.

While only registered migration agents and legal practitioners can charge for immigration assistance in Australia, China abolished the qualification certification for immigration intermediary agencies in 2018.

The streamers that were observed offered one-on-one consultations with audience members to assess their situations and suggest options.

One male “agent”, referred to in this story as streamer A, encouraged his audience on Douyin to seek assistance “if you are unable to improve your own qualifications”.

“Otherwise, the probability of your visa application being rejected is over 90 per cent,” he added.

Another individual, streamer B, said his services would “guarantee” visa application success.

It was common for audience members in streams to identify as workers from labour industries, often residing in Chinese cities with the lowest hourly wages.

Cities in China are unofficially categorised within five tiers.

The country’s capital, Beijing, is considered a high-tiered city, and has the highest hourly wage in mainland China at 26.4 yuan ($5.50) as of 1 January, compared to $23.23 in Australia.

In lower-tiered cities such as Nanning in Guangxi Province, the minimum wage can be as low as 20.1 yuan ($4.21).

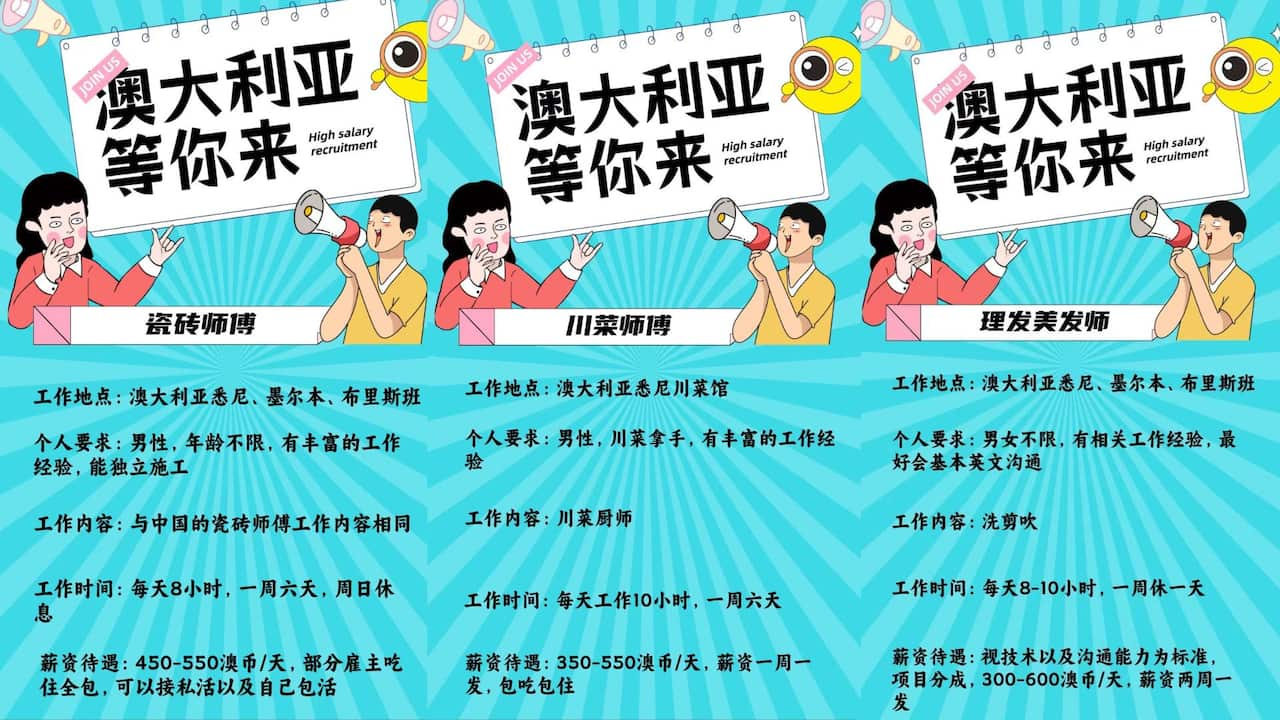

Ads on Chinese social media list Australian hourly wages 10 times as much as what workers can expect in China for jobs such as tile-maker, cook and hairdresser.

Fees among streamers varied depending on the services rendered, including $4,000 to assist with minor tweaks to visa applications, while others demanded up to $60,000 for a package including visa submissions, job searches, airfares, and accommodation upon arrival.

For an Australian temporary skills shortage visa application, service fees among some streamers ranged from between $42,000 to $62,000 — despite the Australian government charging a $1,495 fee to apply.

Among the services offered by streamers were fabricating documents necessary for visa applications, including payslips; travel records to developed countries for people who had never travelled abroad; and white-collar work certificates for workers in blue-collar industries.

In a livestream from October on Douyin, streamer C said the key was to “make you look like a genuine tourist” when applying for a tourist visa, and a “genuine student” if you are applying for a student visa.

Activities to “subvert Australia’s migration system” weren’t confined to China, according to the former deputy secretary of the Department of Immigration Abul Rizvi.

“[These fraudulent activities] are in many countries,” he said.

“Regulating those [overseas] agents is very difficult, if not impossible.”

Part of the problem regarding streamers based in China was authorities, such as the Australian Border Force (ABF), didn’t have the authority to regulate individuals in that country, Rizvi explained.

“It’s [also] very difficult to manage colleges in Australia who know how to fool the regulator into thinking they’re genuine when they’re actually not,” he said.

Rizvi said people caught up in the migration frauds were at risk of being deported or exploited in low-paid jobs.

Those arriving under such circumstances risk becoming stuck in “immigration limbo” without money to return home or encouraged to apply for asylums so they could retain their work rights, he said.

“It ends up creating a large and growing cohort of people in Australia who are unable to go home because they can’t afford it and are being exploited because they must work to survive, but cannot get permanent residency and citizenship. They’re stuck in ‘no man’s land’.”

‘Very small’ percentage use these channels

Immigration lawyer Sean Dong said while streamers played the role to “fulfil” their clients’ aims of working in Australia by “cheating the system”, they target the vulnerable.

“The whole [visa service] system is professionally designed to cheat the [migration] system and profit from it.

“They are targeting those desperate people who really need to work to get paid higher … And apparently those people are not eligible through the normal visa system.”

A “very small” percentage of Chinese students come to Australia through these channels, Sydney-based migration agent Andrew Li affirmed, while the majority arrived with genuine intentions to study.

“Most of the students from China are enrolled in universities and they are really focused on study,” Li said.

Rizvi feared that genuine visa applications would be impacted by the focus among Australian authorities to identify fraudulent ones.

“We need to remember that the bulk of students from China are genuine,” he said.

The Australian Border Force told SBS Chinese the department can refuse granting a visa if the application includes a bogus document, or information that is false or misleading.

“In the 2023-24 year, the department cancelled 5,978 visas where it was found that the person had provided false information, bogus documentation or the visa application contained incorrect information,” a spokesperson said.

“Of these, 129 cancellations were onshore, while the rest were undertaken offshore.”

Consequences of visa cancellation included detention and removal and being subjected to an ‘exclusion period’ of three years for applying for temporary visas, the spokesperson added.

Whilst there is no requirement for those providing immigration assistance overseas to be registered with the the department “encourages people offshore who wish to obtain professional assistance to still use the services of a registered migration agent (RMA) either offshore or in Australia”.

“The OMARA urges consumers who require immigration assistance to check the publically available online Register of RMAs before paying for the services of a migration agent, to avoid engaging the services of an unlawful provider of immigration assistance,” the spokesperson said.

Around 70,000 people are living unlawfully in the country, the Australian Department of Home Affairs estimates, but experts believe the number could be much higher.

As part of its response, the federal government has sought to .

Further, a ban on “ was initiated from 1 July, which prevents temporary visa holders from making onshore student visa applications.

Working under the guise of an international student

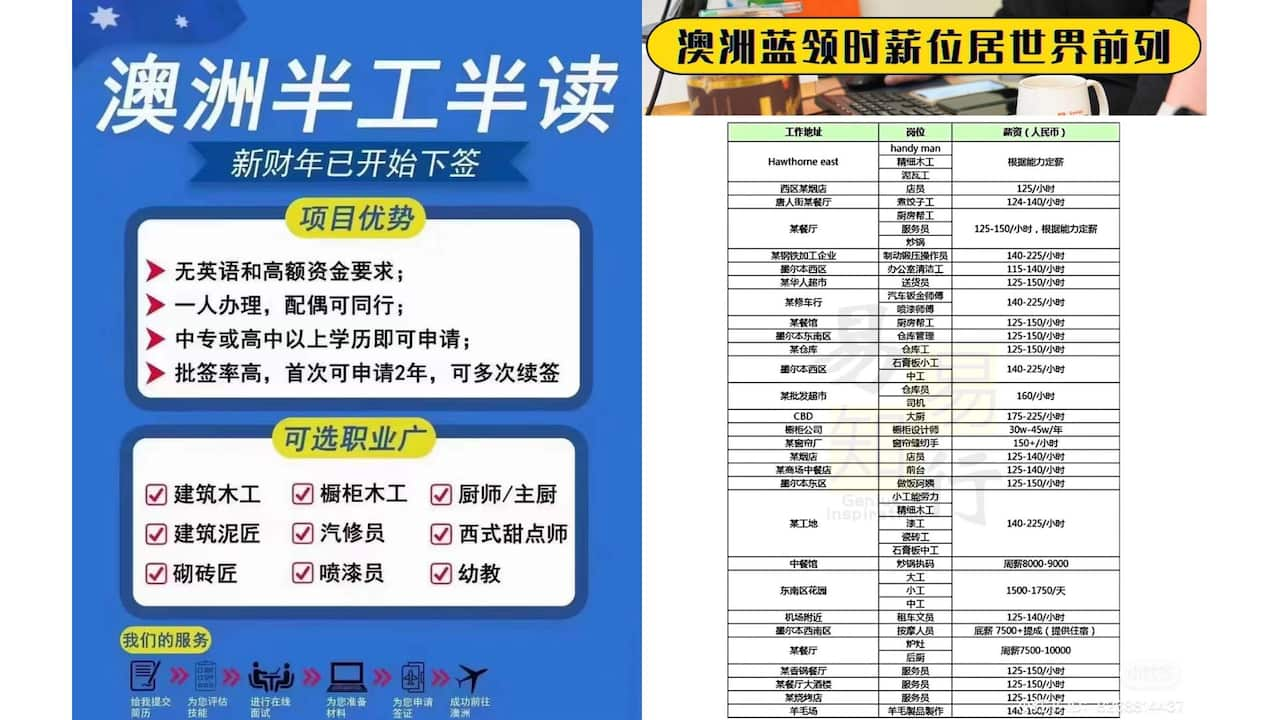

Li said streamers providing migration advice overseas played a key role in marketing a “half work, half study” program to their clients, which is averse to the rules stipulated as part of their student visas.

“These half work, half study programs became popular particularly after Australia re-opened its borders in 2021 following the COVID-19 pandemic,” Li said.

“Some people in China had suffered great financial hardship during the pandemic and at the same time there was a great need for labour in Australia.”

A ‘half-work half-study’ program ad posted on Chinese social media.

One overseas-based streamer advised her audience that “ghost colleges” were aware that students didn’t want to study and that class attendance was not mandatory.

Viewers were also told, “The school we match your daughter with knows that she’s really there to work”.

Li said he hoped visa applications could be handled in a way that only Australian-based agents would be permitted to submit visa documents, though he believed it was “unlikely to happen”.

* name changed to protect identity.

Video editing by Tianyuan Qu