Key Points

- Human Rights Watch estimates that between 2,800 and 5,000 prisoners were executed in Iran in 1988 alone.

- According to Amnesty International, 853 people were hanged in Iran in 2023.

- With at least 166 executions, October saw the highest number of monthly executions recorded in Iran since 2007.

More than 40 years ago have passed since Saeed Eshraghi received two phone calls from his hometown that he can “never forget”.

The Iranian-Australian man’s father, mother, and sister were sentenced to death within two days.

“I received a phone call from my brother, and he told me that our father had been executed with five other Baha’i men,” Eshraghi, 76, said.

“Two days later, he called back and said our mother had joined him, and our sister was also with them.”

Enayatollah, Ezzat and Roya Eshraghi, along with 13 other Baha’is, were hanged in the city of Shiraz in Iran in June 1983 — four years after the Islamic Revolution in Iran and 16 years after the last person was executed in Australia.

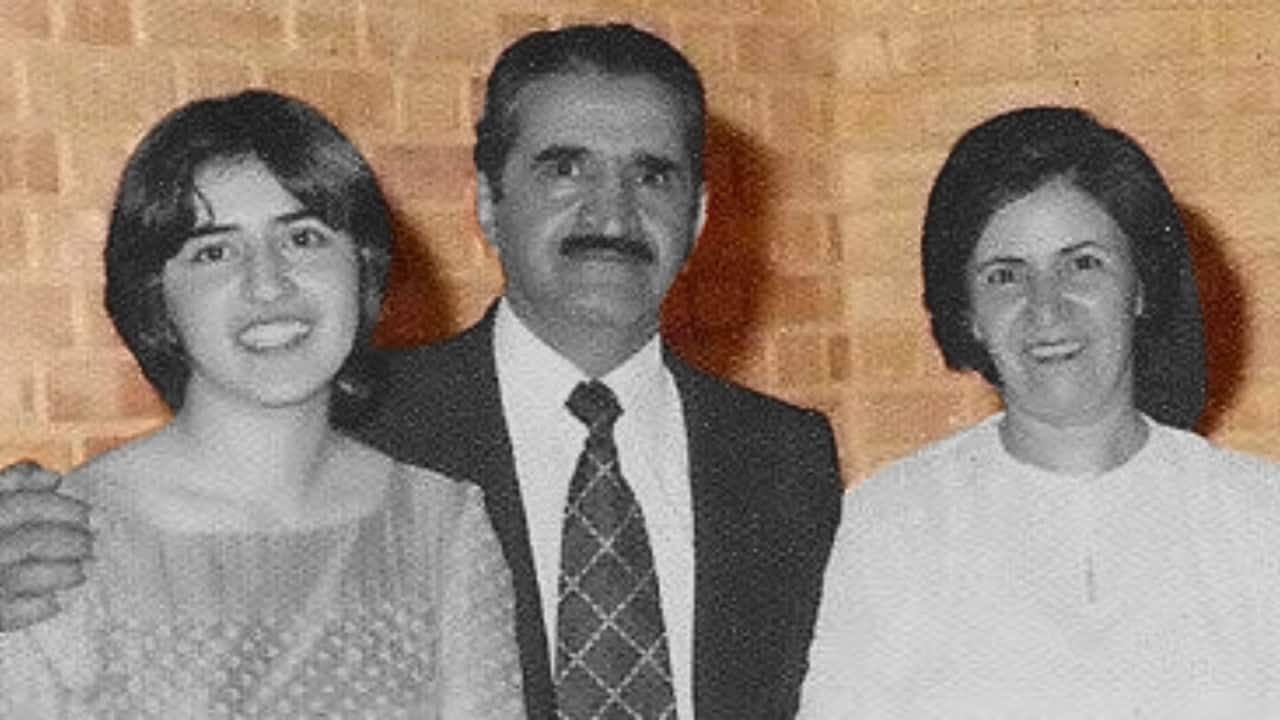

Enayatollah (left), Ezzat (right) and Roya (middle) Eshraghi were members of the Baha’i community in Iran. Credit: Supplied

‘Letting the birds free’

The charges against them remain unclear, but according to the Abdorrahman Boroumand Center, an Iranian human rights group, they were linked to their religion.

With an estimated community of 300,000 people, the Baha’i faith is considered the largest non-Muslim religious minority in Iran.

Eshraghi, who lives in Queensland, said his loved ones did not “commit any crimes”.

“I had two birds in a cage, and after I heard my father was hanged, the first thing that I remember, I took the cage outside, opened the door and let them free,” he said.

“I didn’t want anyone or anything to be in captivity because of me. I didn’t want to hold anything in the cage.

“Everyone should be free.”

The exact number of death sentences imposed in Iran in the first decade after the 1978 revolution is unknown, but Human Rights Watch (HRW) estimates that

In July, the UN’s special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran suggested that executions “during 1981-1982 and in 1988 amounted to crimes against humanity of murder and extermination, as well as genocide”.

“Following the 1979 revolution, the Iranian state executed thousands under the pretext of stabilising the new political order. The executions of political opponents began immediately after the 1979 revolution,” Nahid Naghshbandi, acting Iran researcher at HRW, told SBS Persian.

“Ethnic and religious minorities, including Kurds, Baluchis, Azeris, Arabs and Sunnis, are disproportionately targeted in executions.

“The Iranian authorities have followed the pattern of using execution as a tool to suppress opponents and dissent since, and with each wave of protests in Iran, we see they use this tool.”

‘There is no guarantee’

Figures show that capital punishment is still used significantly in Iran.

According to Amnesty International, 853 people were hanged in Iran in 2023, the highest number of executions recorded in the country since 2015.

Majid Kazemi, a protester arrested during the “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests in Iran, was one of them.

In May 2023, Kazemi, along with Saleh Mirhashemi and Saeed Yaghoobi, were sentenced to death as they were found guilty of “enmity against God” (moharebeh), a charge that Naghshbandi said is “frequently applied to political dissidents and protesters”.

Kazemi’s cousin, Mohammad Hashemi, heard of Kazemi’s death sentence while he was protesting in Sydney against capital punishment in Iran.

“We always heard about people being executed in Iran, but I really didn’t expect this to happen to one of my loved ones. Most of us think that this will happen only to others until we experience it and understand how close the danger is,” he said.

“There is no guarantee. Each of us can face the consequences of capital punishment differently.”

Mohammad Hashemi (right) and his cousin Majid Kazemi (left), who was executed during the “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests in Iran. Credit: SBS

At least eight protesters, including Kazemi, have been executed, with many others facing death penalty charges.

“During the last movement in Iran, judicial authorities drastically increased the use of vaguely defined national security charges that could carry the death penalty against protesters, including for allegedly injuring others and destroying public property,” Naghshbandi said.

“Following grossly unfair trials where many of the defendants did not have access to the lawyer of their choice, authorities issued dozens of death sentences in connection to the protests.”

‘I have forgiven but not forgotten’

According to the Norway-based Iran Human Rights (IHRNGO) organisation, October saw the highest number of monthly executions recorded in Iran since 2007 with at least 166 executions.

The recent surge in the use of capital punishment in Iran compelled Hashemi to join the ‘No to Execution’ campaign and organise a protest in Sydney to mark Human Rights Day.

“I will do anything I can. Human rights violations are happening in Iran in various ways, and the lives of those who are at risk of execution will be our priority,” he explained.

“I believe the situation for these people is similar to Majid, and I have to do the same thing I did [for Majid] to stop their execution. This is undoubtedly a violation of human rights; in any government, no one should have the power to decide another person’s life.

“With each life we save, we get one step closer to victory.”

Six protesters, sentenced to death by the Tehran Criminal Court for their alleged roles in killing a member of the Basij paramilitary force during the “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests in the so-called “Ekbatan Case”, are among those who are currently facing capital punishment in Iran.

Varisheh Moradi, a Kurdish women’s rights activist, is another who has been sentenced to death on charges of “armed rebellion”.

Saeed Eshraghi left Iran for the United States in 1978, and has been living in Australia since 1986. Credit: Supplied

These sentences remind Eshraghi of what he endured 41 years ago.

“Today, when I hear someone has been hanged, it reminds me of my own experience. In general, the death penalty is not the right thing whatsoever,” he said.

“I can say particularly about our family; we have forgiven everybody who caused those unfortunate things.

“But we cannot forget.”