To explore nostalgia and what dwelling on the past can mean for the present, watch Insight’s episode Turning Back Time, on .

Explaining a 2019 visit to the Saigon building where she believes she was born, Kate Coghlan says she doesn’t believe in coincidences.

She had talked with another Vietnamese-Australian adoptee who had traced her life back to this location and, like Kate, adopted out to Australia between 1973 and 1975, in the final years of the Vietnam War.

“She was able to find her baptismal records and subsequently was able to be reunited with her mother, who still attended the same church,” Kate told SBS News.

While Kate hadn’t found a baptismal record for herself, the adoptee had given her the address of the building, where a French priest had run an orphanage and shelter for women experiencing unplanned pregnancies during the war.

It served as “accommodation for unwed mothers to go and have their babies that they knew they weren’t going to be able to keep”, Kate says.

On the second day of Kate Coghlan’s first trip back to Vietnam in the early 1990s, she felt that her “whole being and soul knew I was home”. Source: Supplied

As Kate was standing outside the now private residence with her adoptive father and a Vietnamese priest from the same church as the French clergyman, a taxi pulled up.

Out climbed a Vietnamese-Australian man who’d just flown in from Sydney to visit his aunt — who had lived in the building when it still housed the birthing facility.

“So then we were able to go in and she was showing us around inside the house and she was able to explain, through the priest interpreting, what each room was used for in the 70s.”

Kate Coghlan standing outside the door of a room where children like her were born during the Vietnam War. She was unable to go inside as it is now a private residence. Source: Supplied

One of these rooms was once used as the birthing room, the woman told Kate.

“I’m like, ‘Right, holy s–t. Now I could be standing outside of the room that I was maybe born in’.”

Hopes ‘we would never ask questions’

The discovery of the birthing room was just the newest piece of a still-unfinished puzzle.

Kate is one of the estimated 20,000 to 30,000 children adopted out of Vietnam between 1955 and 1975 — and one of around 1,500 who were adopted and raised by Australian families.

The numbers above are estimates as there are no centralised records for this period.

Since she was in her 20s, Kate has searched for a greater understanding of the circumstances of her birth and, if possible, the woman who had delivered her into the world.

She knew the name of her ‘first mother’ — a term some adoptees prefer to ‘birth mother’ or ‘biological mother’ — but little else.

In addition, she also knew the address of the French-Vietnamese lawyer who’d facilitated her adoption — and where she’d lived for several months before coming to Australia.

“That’s all I’ve got, but it’s massive,” she says.

Sue-Yen Luiten had to track down old maps of Saigon to find the address listed on her birth certificate because many street names were changed after the war. Source: Supplied

Sue-Yen Luiten — who was born in 1974 as Luu Thi Van and adopted by an Australian family in the same year — says the conventional wisdom at this time was that adoptees “would be so assimilated into white Australian culture that we would never ask questions about where we’ve come from and why we’re here”.

She remembers attending Anzac and Remembrance Day ceremonies as a child and teenager and becoming more aware of her biological ties to war.

Australia was the only country she had ever identified with, and these events forced her to grapple with challenging questions.

“I couldn’t help but ask myself if I was participating in these ceremonies in remembrance of those victims who had ‘given’ me life or those soldiers who had fought to ‘save’ my life’,” she wrote in a 2001 speech delivered to a gathering of intercultural adoptees.

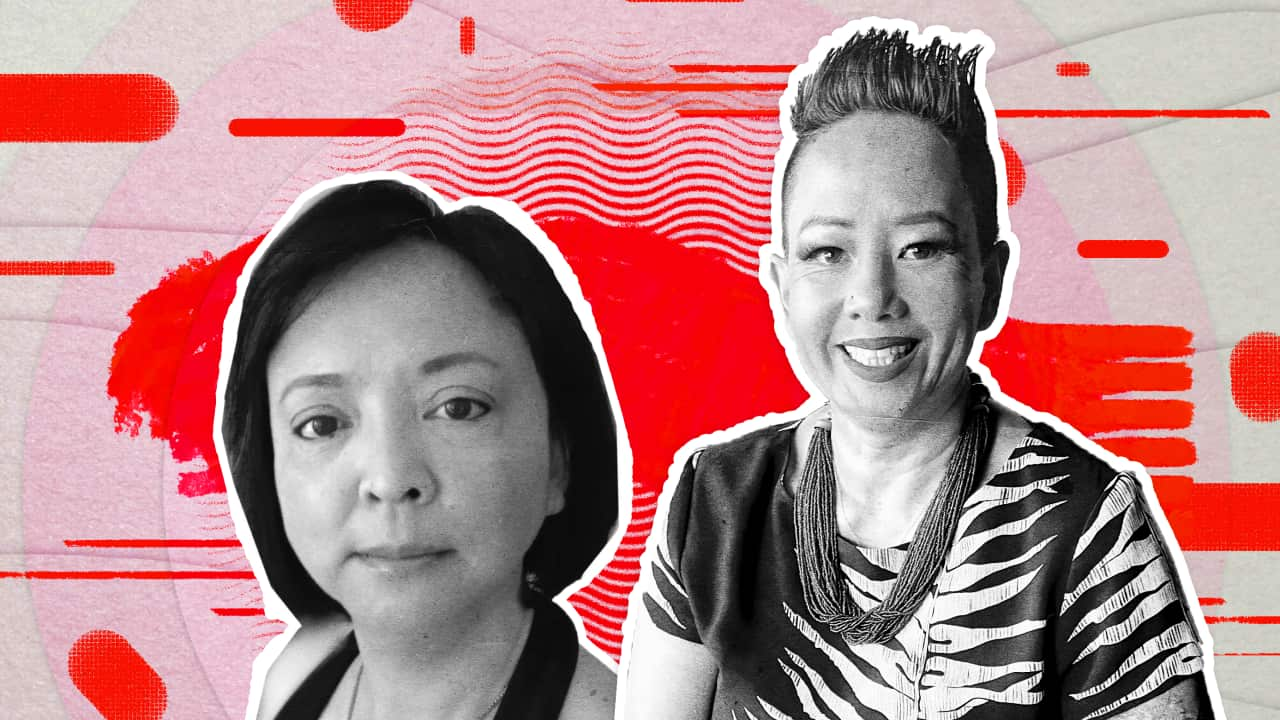

In 2004, a Vietnamese newspaper ran a story on Vietnamese adoptees like Sue-Yen Luiten (left). On Sue’s right is Dai Le, who arrived in Australia in 1979 as a refugee of the Vietnam War and is now an independent federal MP. She has helped many Vietnamese adoptees connect with the country of their birth, Sue says. Source: Supplied

Sue also realised that having been severed from all biological family and cultural connections, she would perhaps have to learn to live with the fact that she’d never fully understand her origins.

Nonetheless, in 2001, she travelled back to Vietnam in search of answers.

She visited the hospital mentioned in her adoption papers and tracked down her birth certificate, which contained her biological mother’s address.

However, she found no trace of her there.

Intercountry adoption’s complex reality

Many Vietnamese infants and children arrived in Australia before 1975, but the public only really became aware of them during the media frenzy that accompanied before the fall of Saigon, subsequently renamed Ho Chi Minh City.

“Around this time, intercountry adoption was viewed as a wholly positive intervention,” Sue says — but this would change.

While government officials, adoption agencies and adoptive families had been able to contribute to intercountry adoption practices and the discourse surrounding it, adoptees were not.

“For 17 years, we were silent,” Sue says. “We were busy just growing up.”

Then, as this group transitioned from “babies with no voice” to adults who could speak about the complex reality of their lives, the discourse began to change.

“It was this massive import into empowerment,” Sue says of the period in the late 90s and early 2000s when many Vietnamese adoptees entered their 20s, initiating “a reckoning of theory versus reality”.

“It’s an uncomfortable conversation, but essential to ensure the rights of the child remain the priority.”

Vietnamese adoptees from around the world gathered at Paragon Saigon Hotel in April 2015 to mark 40 years since the end of the war. Source: Supplied

In the time that these adoptees were growing up, more information also emerged about the circumstances in which some came to be separated from their parents.

In 1988, the Australian director of International Social Service acknowledged that some Vietnamese adoptees had only been temporarily placed in orphanages

“The heartbreaking image for me is the women that went back,” Kate says.

They gave their babies to the authorities in good faith that they could come back when it was safe to get them, and then they returned and they were not there. They were gone.

Kate Coghlan

When Sue first went back to Vietnam, there would be several minutes of “just scrolling screens of missing person ads” shown on TV twice a day, she says.

“The disruption (of the war) to their family units was huge.”

Sue-Yen Luiten placed a missing persons ad on Vietnamese television in 2004 (top), and also handed out cards (bottom), in the hope that someone might recognise her face, name, date of birth, or her mother’s name: Hanh. Source: Supplied

A lot riding on this

In October, Sue did a DNA test through Ancestry.com, which identified a biological relative.

Because of the genealogy service’s privacy rules, she doesn’t yet know this person’s name or location, but she’s reached out to see if they want to talk.

For Vietnamese adoptees like 53-year-old Jamie Fry, DNA searches were integral in finding their biological relatives.

After getting a half-brother DNA match several years ago, Jamie had his first face-to-face meeting with his birth mother in 2022,

“It was something I’ve dreamt of all my life,” he said of the meeting at that time.

“I’ve got to know them over the years but the actual face-to-face and being able to give them a hug and all of those things — it was absolutely brilliant.”

Jamie Fry returned to the US to visit his birth mother for her birthday in December 2023. Source: Supplied

Now, as the 50th anniversary of the war’s end approaches, Sue and Kate hope to provide more people of their parents’ generation the opportunity to utilise DNA technology.

In April, a group of adoptees, friends and family will travel through Vietnam on bikes, spreading awareness of DNA tests and databases, and offering to cover the costs for those who want to take one.

They’ll also offer people who were separated from their children during the war as much assistance as they need, Sue says.

“We are going to support them from the beginning to the end of this journey, or as long as they need us to.”

A small group of Australian adoptees visiting Vietnam during the 40-year anniversary of the war’s end took a few days out to spend time at a children’s home in the city of Vũng Tàu. Sue-Yen Luiten and her family have supported the care of these children for many years. Source: Supplied

“You think about generational amnesia, who haven’t we connected with? Probably the generation of our mothers and our fathers,” Sue says.

“There are always infinite pieces of the puzzle, but there is one piece with which we are definitely running out of time: finding that particular cohort, the piece that unlocks the very core of who I am today.”

“The thing that stays with me … that really motivates me is the thought that my mother is searching for me.

“If I don’t reach out and create pathways for her to find me, then I am not honouring her spirit that lives within me.”

Because of the widespread trauma surrounding the war years, the upcoming trip to Vietnam had to be organised carefully, Sue says.

“There’s a bit of resistance because there’s an awkwardness about reaching out to people of a certain age group in Vietnam, or in our Vietnamese community here,” she says.

“Some mothers and fathers have been able to talk about their children they had during the war about that separation and some haven’t been able to say anything.

“We’re just letting the community know we are there.”

Hopes for connection

Both Sue and Kate stress that their search for connection with their country of birth is no reflection of the love they have for their adoptive families.

For instance, it was “very important” for Kate that her adoptive family came along on her first trip to Vietnam “because it’s as much their story as it is mine”.

However, given their age, their adoptive families won’t be joining them on the ride, during which they also plan to help other adoptees immerse themselves into Vietnamese culture and distribute care packages among the elderly.

Kate Coghlan loves eating like a local whenever she returns to Vietnam. Her adoptive family and daughter do too. Source: Supplied

Organising the event has brought Kate “an immense sense of pride”.

“I feel like we are creating a tangible legacy for fellow adoptees, Vietnamese mothers and future generations that are affected by intercountry adoption.

“It’s also a time … for us to come together to share stories, to connect with other adoptees that have similar life experiences to me, to us and just acknowledge the gravity of what 50 years means.

“And hopefully, we can help adoptees connect with their first families and, who knows, maybe even mine.”

And for more stories head to , hosted by Kumi Taguchi.

From sex and relationships to health, wealth, and grief Insightful offers deeper dives into the lives and first-person stories of former guests from the acclaimed TV show, Insight.

Follow Insightful on the , , , or wherever you get you get your podcasts.