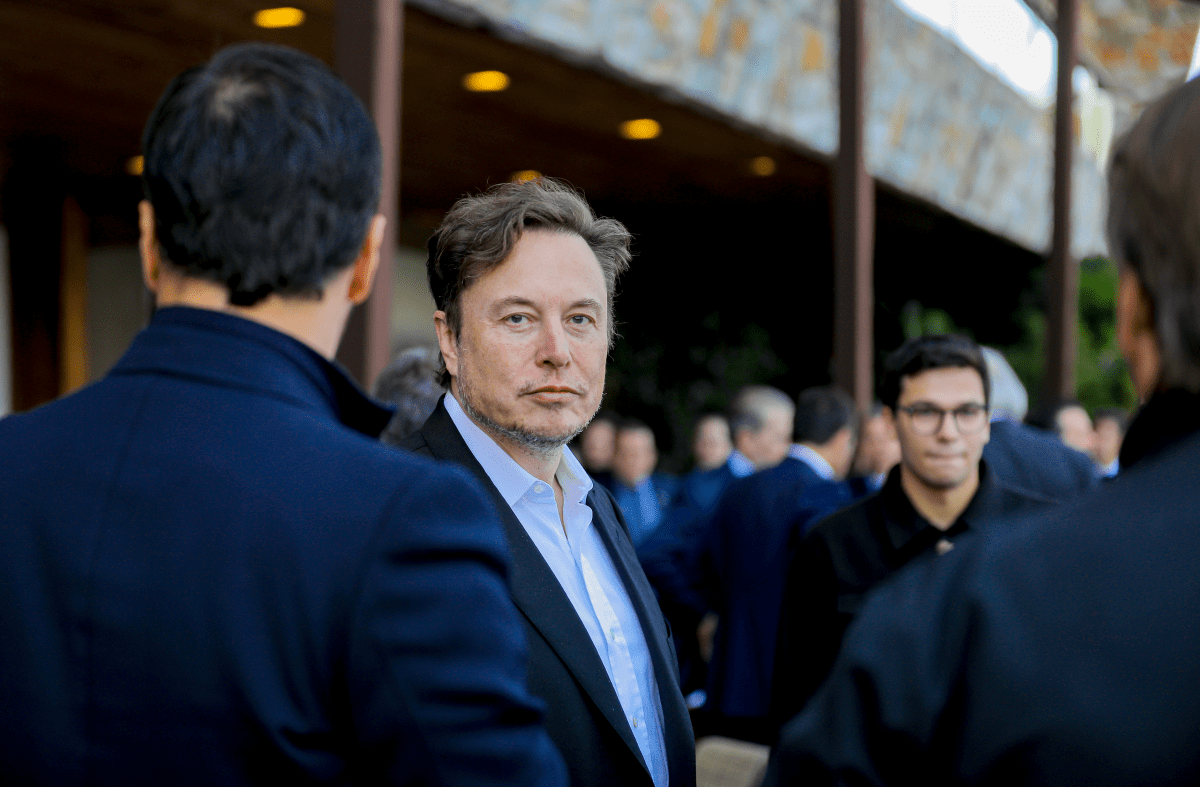

On July 16 2024, Elon Musk shouted from the proverbial rooftops that he will move SpaceX out of California to Boca Chica, Texas. By his own admission, he is not moving only for corporate advantage, value, or profitability, but also for politics. (He is also moving X, aka Twitter, from San Francisco to Austin, likewise for political reasons; he originally bought Twitter for ideological reasons.)

Ironically, Musk’s announcement came the day after another Musk company, Tesla, reversed a large number of recent California layoffs in Fremont, CA. Likewise, only two years after moving Tesla’s management to Texas with great fanfare, he brought the global engineering team back to Palo Alto, CA.

While Elon Musk’s resources may permit him to do whatever he wants, I suspect the SpaceX story will end up looking a lot like Tesla’s. If so, in a few years, SpaceX management might in a few years be right back where they started.

It is very easy to say you are moving a company.

It is only a little bit harder to actually move a company of programmers and office workers. Aside from employees who may not want to go, the barriers to doing so are relatively low.

Moving a manufacturing operation like that of the Falcon 9 is a whole different kettle of fish. You’re not just moving computers and monitors and people to another already furnished office. You’re moving multiple entire factories, including jigs, tooling and heavy machines.

In addition, you are moving or recreating institutional knowledge and skilled labor.

A finely honed manufacturing operation like that which produces the Falcon 9 has a culture — a network of interpersonal relationships between and among managers and engineers. They have expectations and ways of doing business together — all of which have to be recreated at the new location without disrupting production. The barriers to such a move are very high.

Musk seemed to acknowledge as much when he said he is moving “SpaceX headquarters.” As long as SpaceX continues to build the Falcon 9 and hardware like the Merlin engines and the Dragon Capsule’s “Trunk,” manufacturing is likely to stay in California.

One need look no farther than Boeing to see what can happen when you move management to a location remote from manufacturing. That breaks the webs of communications — the institutional and personal connections — that collectively create trust and efficiency. Boeing has seen more than two decades of turmoil since they started moving engineering jobs, then management, out of the closely knit aircraft manufacturing culture in Seattle. They have lost market share, enormous corporate value, and possibly even their future as a going concern.

Humans are networking social animals, and that is no less true of engineers performing precisely coordinated manufacturing operations than it is of musicians performing music from a set of scores. Any musician who has attempted to play on Zoom with their bandmates at remote locations knows that distance weakens those connections, and Zoom can only go so far to replicate them. Building Falcon 9s or Boeing 787s with high cadence and precision requires coordination as tightly synchronized as that of an orchestra’s percussion line.

But unlike Boeing, Musk is not preparing to move his headquarters staff from Seattle to Chicago, or to the suburbs of Washington DC. He plans to move managers from the rich cultural resources and traditions of the Los Angeles area to literally the middle of nowhere. The SpaceX culture is famously workaholic, and SpaceX managers seem expected to have little life outside of the company. The same may not be true of their families.

In the past, Musk has stressed the importance of vertical integration and tight coordination to the success of SpaceX. Musk now seems willing to abandon those ideas, and severely stress test SpaceX’s corporate culture in order to advance an ill-defined political agenda.

As Boeing’s sorry recent history attests, these moves are unlikely to increase the efficiency or reliability of Falcon 9 production and operations, at least in the short term. That will have knock-on effects on costs as well as on the frequency and reliability of launch, which could affect market share just as serious competition for the Falcon 9 is beginning to materialize. Even without these issues, in a few years, SpaceX may no longer have its current near-monopoly on medium launch, and may face increased pricing pressure.

Starship is being developed to replace the Falcon 9, and both assembly and Starship management are likely to remain in Texas and Florida. Recent test flights have shown great promise. Starship is not yet ready for the limelight, and for now SpaceX’s market share and cash flow (and funding for Starship development) most likely are largely dependent on the Falcon 9 and the efficiency of its California operations.

Musk’s stated reason for the move is a new law in California allowing underaged children to change their gender identities without third parties informing their parents. This may have resonance within Musk’s own family, where one of his children is reportedly estranged over just that issue; Musk told Jordan Peterson in a July 22 interview for The Daily Wire that his transgender daughter was in fact “dead” to him. Whatever the merits or otherwise of that law, it seems expensive and rather precipitous to move multiple entire companies — many of whose employees may support the law — for that reason.

Musk likely has the resources to see the politically motivated SpaceX move through, and maybe to solve some of its potential problems. Those are resources that will not be available for Starship development or his Mars ambitions.

Investors and space advocates alike should take note. They may want to invest to encourage a wider and more diverse pool of companies. Companies that do not put the un politics of their CEO ahead of the vital business of exploring and utilizing the rich resources of the inner solar system.

Donald F. Robertson is a retired space industry journalist. He is also a musician, playing percussion for Scottish dance bands — both live and via Zoom.