The Pacific Northwest is emerging as a staging ground for Latino political representation, as a trio of federal elected Latina officials from the region face their first reelection campaigns, with others potentially joining them in Congress.

From 2011 to 2023, former Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler (R-Wash.) was the only federal elected Hispanic official from the Pacific Northwest.

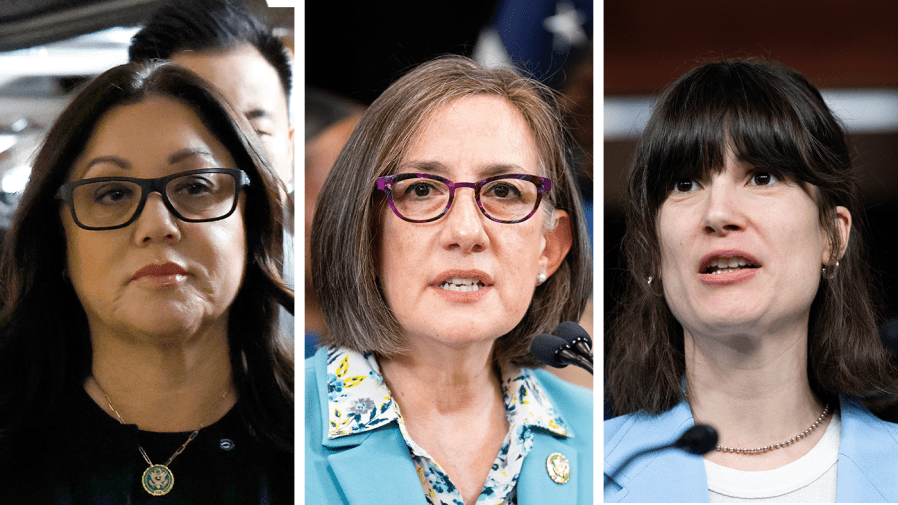

Though Herrera Beutler lost her reelection bid in 2022, Reps. Andrea Salinas (D-Ore.), Lori Chavez-DeRemer (R-Ore.) and Marie Gluesenkamp Perez (D-Wash.) won their elections and tripled the region’s Hispanic representation overnight.

“Latinos have played an essential role in our economy and way of life in Oregon for decades. My district in the Willamette Valley has long been home to a vibrant Latino community, and we’re now the largest and fastest-growing minority group in the state,” Salinas told The Hill via email.

“That kind of growth has made it hard for pundits to ignore us. It also increases the need for representation at all levels of government, especially at the federal level, to ensure that our voices are heard.”

The region’s Hispanic congressional footprint could expand in 2025, with Gresham City Councilor Eddy Morales running in the Democratic primary to replace retiring Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.) and Washington state Sen. Emily Randall (D) in the primary to replace retiring Rep. Derek Kilmer (D).

The diversification of elected officials is also being felt at the local level.

Last year, the Washington state legislature created its first-ever Latino caucus, a reflection of the group’s growing numbers.

In Oregon, 2022 saw a reduction in the number of Latinos in the legislature, in part because Salinas left the state House to run for her federal seat. The Oregon legislature became more diverse overall that year despite losing some Latino representation, with the election of five Vietnamese Americans and a Native American.

Still, the trend is one of growing Hispanic representation – if Salinas and Chavez-DeRemer are reelected and Morales takes Blumenauer’s seat, half of Oregon’s House delegation will be Hispanic.

Though Hispanics are among the fastest growing groups in Oregon and Washington, demographic change doesn’t tell the whole story.

According to 2023 population estimates by the U.S. Census, 14 percent of Washingtonians and 14.4 percent of Oregonians identify as Hispanic.

In 2010, 10.5 percent of Washingtonians were Latinos, as were 11.2 percent of Oregonians, yet Herrera Beutler and former Oregon Rep. Sal Esquivel (R) are the only two Hispanic names in the rolls of either legislature for that year.

In both states, social policies from education, to health, to criminal justice have created the space for Hispanics, even the undocumented or mixed status families, to engage politically, say local advocates.

“We were fighting. We were just reacting against anti-immigrant policies. And at some point, we decided we should actually do proactive policies. And so for years now we have passed policies, again, at different levels, state, county and city levels in different areas in Washington that ended up giving this protection that the community needs,” said Maru Mora-Villalpando, a progressive community organizer in the Seattle area.

“And one of the reasons is not only that people can live peacefully, but that they can actually participate and understand the power, right? We say it’s important to vote, but voting is not enough.”

Progressive organizing has become a feeder league for aspiring politicians in a region where both states look solidly Democratic but have a much more complicated spectrum of ideologies at the local level.

Randall, the state senator hoping to replace Kilmer, said she was inspired to run as a reaction to former President Trump’s surprise win in 2016.

“I ran in the district where I grew up but where, since Congressman Kilmer had left the state Senate, we had had Republican representation. And a lot of folks told me that, you know, queer Latina who worked at Planned Parenthood couldn’t win in that district. And we won by 102 votes on a 70,000 manual recount,” said Randall.

Outside of liberal cities including Seattle and Portland, the Pacific Northwest is host to an eclectic tapestry of ideologies that sometimes seems incompatible with national issues.

“I describe to people who don’t know my district that we’re definitely more libertarian than Democrat or Republican. You know, people want to live in a rural community because they don’t want to live right next to their neighbor, right? They live in a rural community because they don’t want the government to, like, get their hands on their guns, their uterus or their marijuana. That’s the vibe,” said Randall.

That vibe is reflected in the region’s federally elected Latinas.

Gluesenkamp Perez flipped Herrera Beutler’s seat after the then-incumbent was eliminated in a jungle primary, leaving Gluesenkamp Perez and MAGA-aligned Republican Joe Kent to compete in the general election.

The Democrat won by less than a percentage point – and is potentially facing a rematch against Kent – and she has held staunchly centrist positions, including voting for a Republican resolution to condemn the Biden administration’s immigration policies in March.

“First of all, identity doesn’t really match progressive ideology, right? We do have a lot of more way more representation that we did 10 years ago in regards to Latinx political officials, especially in the in state Senate and House,” said Mora-Villalpando.

“The vast majority of them are progressive, but there’s ones here and there that are not, regardless of their identity as Latinos or Latinx. And I think it has to do a lot with their constituency and the history of the place.”

Hispanic agricultural workers have seasonally worked the region for decades, but like in other parts of the country, many migrant populations decided to stay put following the 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigration Responsibility Act, which made repeat border crossings more onerous.

The region has also attracted immigrants from other states, including California in the mid-1990s, which have either cracked down on undocumented immigrants or restrict the social services available to foreign nationals.

“My mother was able to bring us up there by taking care of farm workers’ kids, and also making lunches for farm workers. So I think just because of the large agricultural, like, economy here in terms of lumber, the pine, I think we have the largest Christmas tree farms here, and also kind of fruits and vegetables. I think a lot of that work has attracted people here,” said Morales, the city councilor running to replace Blumenauer.

“And then you know, like myself, I became the first in my family to graduate high school, the first to go to college. Our second generation just becomes part of the community here.”

Like other Cascadians, Hispanics in the region show different political and cultural tendencies in urbanized coastal areas, and across the mountains in central and eastern Oregon and Washington.

But Hispanic populations are growing on either side of the mountains, with political consequences. In Washington’s central Yakima Valley, for instance, a federal judge ordered the state to adopt an electoral map uniting Hispanic communities to create a Latino-majority district ahead of the 2024 election.

Expanding the Latino footprint in the region has often been an uphill battle.

In 2022, the Congressional Hispanic Caucus’s (CHC) campaign arm, Bold PAC, fought national Democratic leadership in a $15 million primary – with Bold PAC’s candidate spending about 10 percent of that amount – to get Salinas elected.

“I’m honored to be one of the first Latinas to represent Oregon in Congress, and the fact that voters elected me in a crowded, 9-person primary speaks volumes about the power of the Latino electorate. But we are not a monolith,” said Salinas.

“More Latino representation will bring more diverse perspectives to the table, and politicians will need to keep an open line of communication with our community if they want to win the Latino vote. I’ve worked hard to create those connections and I will continue meeting with folks on the ground, listening to their concerns, and bringing them back with me to Washington D.C.”