Key Points

- The Chang Thai Market Grocery store was opened in 1985 and his believed to be Australia’s longest-running.

- Opened by Thai migrant Danny Niravong, the store has remained in his family’s hands.

- Food is a key way diversity is reflected in Australia, says expert.

In 1978, Paiboon (Danny) Niravong arrived in New South Wales from Udon Thani, Thailand.

Like many migrants, he worked long hours in factories and picked up part-time jobs to make ends meet, including as a shop assistant for a Thai-Laotian grocery store in Cabramatta — an area that would later become a vibrant hub for Southeast Asian communities.

“I moved from home to study Chinese in Laos, then came to Australia in 1978 because I had a friend and relatives here. I believed it would offer me better opportunities,” he told SBS Thai.

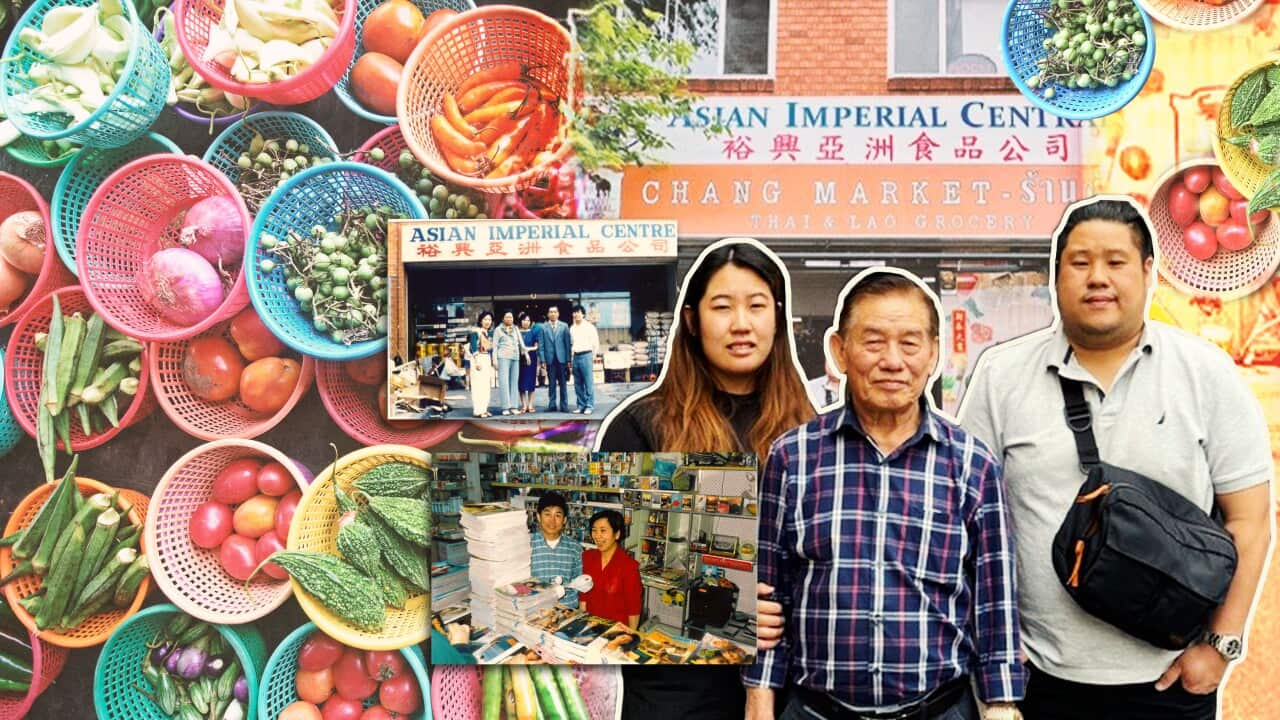

Staff stand outside the Chang Market Thai Grocery store in Cabramatta, New South Wales, which has been trading since 1985. Credit: Paiboon Niravong

But Niravong saw more than just a job.

“I was working with the shop owner when he asked if I wanted to buy the business. I thought, why not? Cabramatta had many Vietnamese, Cambodians, Laotians and a few Thais — we share similar foods and ingredients. So, I negotiated the price and started from there,” he said.

With determination and a deep understanding of his community’s needs, Niravong transformed the small store into the ‘Asian Imperial Chang Market Thai Grocery’ known today as the Chang Market Thai Grocery.

Starting with canned goods and basic Asian staples, it grew into a cornerstone of the local community, supplying Thai ingredients to migrants craving the tastes of home.

Back then, there was no Thai Town. People from all over Sydney came to Cabramatta to buy Thai ingredients

Paiboon (Danny) Niravong

Paiboon and Vannida Niravong used to stock newspapers, magazines, CDs, and movies as a way for people to stay connected to home. Credit: Paiboon Niravong

Today, the store is run by Paiboon’s son, Edward Niravong, who continues the family’s legacy, serving both long-time customers and new generations.

“We still have customers who’ve been coming here since we first opened. They’re like family. I’m proud that we help people maintain their connection to Thai culture through food. Without places like this, people might be stuck eating just chips and burgers,” Edward said.

Forty years after opening its doors, Chang Market Thai Grocery remains a vital link between cultures. Despite the rise of online shopping and food delivery services, the personal connection between the store and its customers remains irreplaceable.

“We’ve built relationships that go beyond transactions. It’s about community, tradition, and helping people feel at home — even when they’re far from it,” Edward said.

How migration shaped Australia’s dinner tables

In the 1970s, sourcing authentic ingredients was a challenge tied to identity, community and belonging. Yet, this very challenge laid the foundation for the rich and diverse food culture that defines Australia today.

Laurie Nowell, Media Manager at Adult Multicultural Education Services (AMES) Australia, explains.

“Migration has had a massive influence on Australian food culture. It’s probably the most visible impact that migration has had in Australia,” he told SBS Thai.

“If you go into any suburb or town, you’ll see restaurants with cuisines from all over the world. It’s been an important feature of the way people eat in Australia.”

Before this transformation, Australian cuisine was largely rooted in British traditions. However, the post-World War Two era marked the beginning of significant change.

“After the second World War, things really opened up. In 1951, the first espresso machine was imported to a café on Lygon Street in Melbourne, sparking the coffee culture Australia is now known for,” Nowell said.

“Migrants from Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, and more recently, the Middle East and Africa, brought their cuisines with them.

“(Nowadays) Australia has become one of the most diverse food cultures in the world — you can find food from anywhere.”

The evolution of Thai food in Australia

Today, Sydney’s Thai Town is the second-largest Thai enclave outside Thailand, filled with bustling eateries and markets that mirror Bangkok’s vibrant streets. But back in the 1970s, Thai Town didn’t exist.

Banh Thai, believed to be Australia’s first Thai-owned restaurant, opened in Melbourne in 1976

It wasn’t until the mid-1980s that other Thai grocery stores like Chang Market appeared, alongside businesses that imported essential Asian ingredients.

“We ordered goods from Thailand through import-export companies. Shipments took about four weeks. For things like newspapers, magazines, CDs, and movies, we used air freight. That was the only way people could stay connected to home.”

Adapting flavours, preserving culture

In the early years, even Thai restaurants had to get creative. Authentic ingredients were hard to find, leading chefs to substitute with what was available.

It wasn’t unusual to see carrots, broccoli, or capsicum in dishes that traditionally featured Thai eggplant, bamboo shoots, or holy basil.

Oradee (Som) Thammarak, head chef and owner of a southern Thai restaurant in East Melbourne. Credit: Oradee Tummaruk

Oradee (Som) Tummaruk, head chef and owner of Ranong Town, a southern Thai restaurant in East Melbourne, has seen this evolution firsthand.

“Twenty years ago, finding authentic Thai ingredients was a real challenge. Today, with better access, Thai restaurants can offer dishes much closer to what you’d find in Thailand. Authenticity helps us stand out in a competitive market,” Tummaruk told SBS Thai.

Athita (Tam) McNab, a Thai migrant in Davenport, Tasmania. Credit: Athita McNab

For many migrants, food is more than just sustenance — it’s a connection to culture, memory and identity.

Athita (Tam) McNab, a Thai migrant in Davenport, Tasmania, told SBS Thai about the challenges she faced even today sourcing ingredients.

“I cannot live without Thai food, especially Isaan dishes. When there wasn’t an authentic Thai restaurant or a Thai grocery store in Davenport, I flew to Sydney just to eat,” she said.

“Whenever we gather with friends, we make som tum. If we can’t grow or make the ingredients ourselves, we order them online.”

Listen to SBS Thai Audio on Monday and Thursday from 2pm on SBS 3. Replays from 10pm on Monday and Thursday and Saturday on SBS2. Listen to past stories from our podcast