In a four-bedroom house, in one of Brisbane’s wealthiest areas, I took off my shoes at the door of Percy’s* place. He welcomed me in and showed me around.

“This is the bedroom … the walk-in wardrobe … the guest room,” he rattled off. “I had someone staying here the last couple of weeks.”

On the same street, a $1.75 million house — a newer home — sold around the same time he moved in. But Percy pays nothing. He doesn’t own the place. He’s not renting or house-sitting either. He has been squatting in someone else’s house for seven months.

See inside Percy’s squat in this short documentary:

“I’m sort of a bit out of place like I’m walking around in disguise,” the 34-year-old said, reflecting on the neighbourhood.

The first few nights he slept here, “I would just wake up and laugh.”

Percy was once a paying renter in the same place before moving on to another rental. But he moved back in when he found it had been left empty for months.

“I would say the place is nice; I’m not sure everyone would agree.”

Having lived there before, he already knew the house was not in great condition, with mould on the ceiling, holes in the floor, and water damage splotched throughout the place.

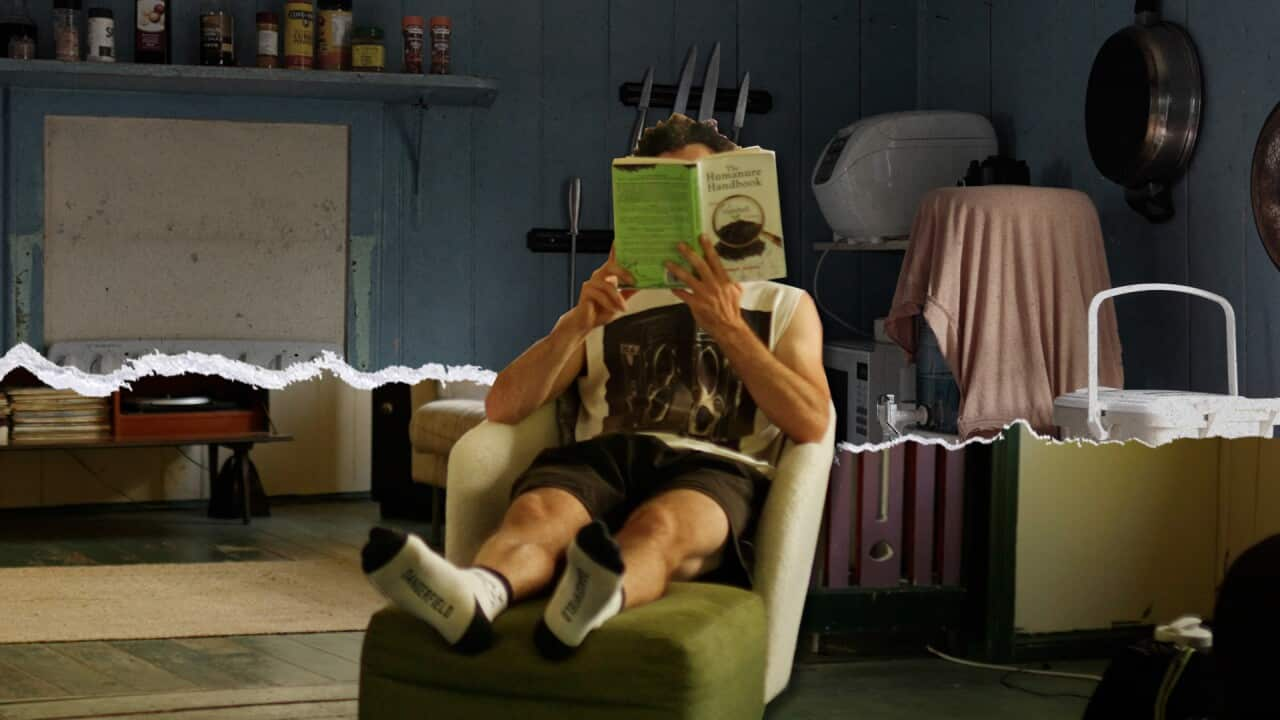

Percy pottering throughout the house he’s been squatting in for seven months. Credit: SBS The Feed

He said it’s why the house was left empty in the first place, now in a state of disrepair that is likely not fit to live in – though he doesn’t mind.

And with rent rising in all capital cities across Australia (excluding Darwin) in 2023 and 2024, he felt motivated and justified to try.

Percy moved into the place in 2023.

He said that if tax incentives like negative gearing can support property investors, this is his way to “take something back”.

Percy’s kitchen setup. Credit: SBS The Feed

“We have such an inequitable society. Why perpetuate that by continuing to pay rent or contribute to the amassing of wealth that a handful of people have?” he said.

“I reconciled myself to being a renter in the first place … then I realised maybe there was another way and I just went for it.”

For Percy, he says the move would also free up somewhere else for someone else, he reasons.

“It sounds sort of silly, but I just wanted to have the space, that sort of freedom that I wouldn’t otherwise be afforded renting or share housing.”

Percy in his four-bedroom house. Credit: SBS The Feed

There were some clear adjustments made to the house to fly under the radar. The furnished house is almost passable as “normal” until you clock the bottles and barrels of water scattered through the rooms.

While there was electricity, there wasn’t running water and Percy showered using a pot of water instead.

And for a toilet … buckets.

“I just squat over the top, and then just throw some sawdust, cover it like a litter tray, like a giant human cat,” he said.

The waste becomes compost for his garden.

Percy squatted there for over seven months before moving on.

What are the laws around squatting?

In Australia, it may not be illegal for a squatter to enter a property if it looks abandoned and the doors are unlocked. If the door isn’t unlocked, the squatter could be criminally charged for breaking and entering. If a property owner asks a squatter to leave and they stay, they are trespassing.

Why do these laws even exist? John Bui – a principal lawyer at JB Solicitors in Sydney, said Australia’s squatting laws exist to encourage mindful and efficient use of the land, with owners having obligations of their own to maintain a property.

“If they’re not maintaining that land, and they’ve abandoned the property, then it’d be a waste not to allow someone else to use it,” he said.

In Australia, a claim for the title could be possible under adverse possession laws in all Australian states if a person has managed to squat there long enough — 12 years in all states, bar Victoria, where it is 15 years. There is no provision for adverse possession in the ACT and NT.

All Australian states have adverse possession laws or ‘squatter’s rights’. There are no such rights in the ACT and NT. Credit: SBS The Feed

In 1998, Sydney property developer Bill Gertos walked into a three-bedroom house, taking it as his own after learning the elderly owner had died.

He renovated, changed the locks and put renters in the place for 20 years — so essentially had them squatting for him.

In 2018, he won the title to the house, and he sold it in 2020, making $1.4 million.

A Sydney property developer won the title to this $1.4 million house under squatter’s rights in 2018. Credit: SBS The Feed

But unlike this house, many end up trashed.

There can also be trouble for owners to push them out, and for some people like Emma Cook, it can pose a safety concern.

Emma came home late one night after being away on a short trip and found a man living on the front of her property.

“We heard this mighty scream, this piercing scream of my sister, and she ran out and said, ‘there’s a man, there’s a man’. My sister was crying, I started crying,” she said.

Emma Cook said her run-in with a squatter left her uneasy about personal safety. Credit: SBS The Feed

It was her dad who talked him off the property. She later realised the man had been staying there on and off for months and was keeping tabs on their movements.

“It was just an innate fear of coming home. I’d always make sure I’d leave lights on,” she said, adding that while everyone “has the right to a roof over their heads” – this was not the way to do it.

Emma installed a security camera and removed all the bushes around her property to quell some uneasiness. But with her husband going away often for work, it took months for her to feel okay with being alone with her daughter.

“It did actually affect me for quite a time afterwards.”

Australia’s empty houses

There could be up to 136,000 empty houses in Australia, according to 2023 estimates from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

There have been some attempts to reduce this number in Australia, including a vacant land tax on residential properties in parts of Victoria.

This month, Jordan van den Lamb — known as Purple Pingers online and for his rental advocacy work — showed up to an unoccupied Melbourne home and draped signs all over the property to draw attention to its abandonment.

“This house has been empty for 15 years,” one sign read, before he was moved along by Victoria Police.

But Professor Cameron Parsell from the University of Queensland says, “Fixating on the empty houses is just a distraction.”

“I don’t hold great hope that we can solve homelessness or the housing crisis by merely intervening in the empty houses.

“We need to eliminate the need to squat by ensuring that all citizens have access to housing that’s affordable.”

James can’t afford a rental, so he’s squatting instead

Over two months, The Feed contacted over a dozen people who had squatted or were squatting – and the reasons why they did it were mixed.

One pensioner in regional Victoria said he would be homeless if he weren’t squatting, with only one option on the rental market he could afford. Some did it to save money for a property deposit, and others did it as an act of rebellion.

With the secretive nature of it all, there is very little research into how many people are squatting in Australia.

James* and his partner are squatting to avoid sleeping rough. Source: Supplied / Lee Chantler/ SBS The Feed

But Parsell says, “What we do know from the limited evidence that is available both in Australia and internationally is that most people squat because they have nowhere else to go.”

James* falls into this category.

“Across the road is a big tent city,” James tells me from the woman’s centre-turned-squat we’re standing in.

Gesturing roughly toward the street, he said: “It’s this or out there.”

The women’s centre has been empty for years, James said.

“We were just down the road. We were desperate for shelter,” he told me as we stood inside the abandoned property he’s been squatting in for over a year with his partner.

The property shares a fence with a public school, who he says knows of their stay.

“I think they prefer us being here. When we ran into it, it was just a mess, there were syringes everywhere, the entire place was open,” he says.

In the biggest room, now their living room, long-life food and a portable gas cooktop are as close as they can get to a kitchen without electricity and running water.

He showers at the 24-hour gym he goes to.

If these places are just sitting there, I don’t see why not.

James*

There are makeshift barricades fashioned from slabs of different materials around the place to prevent people from wandering in. It’s helped.

James previously worked regularly as a forklift driver, but when shifts dried up and he was moved on from his last accommodation, he quickly found himself out of options.

“I feel like s–t. This is not what I wanted to do,” James says. His plan is to find stable work and save enough money for a bond to return to the rental market.

“I’m working again but it’s just not enough.”

When he has enough money to put a bond down for a rental or is kicked out, whichever comes first, they’ll move out. But until then, he’s posting callouts on social media, hoping to “pay it forward” to someone else in need of housing.

“I don’t see why not. If these places are just sitting there, I don’t see why not.”

*Not their real names.