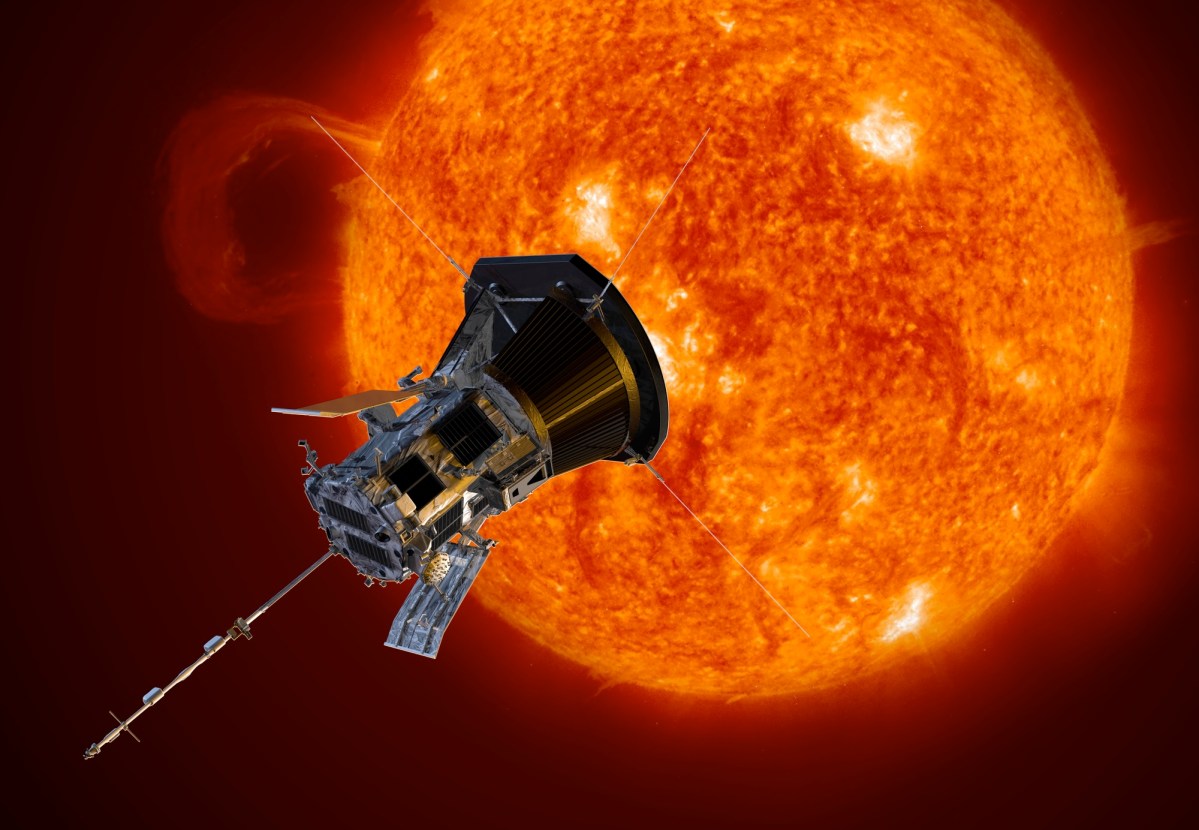

WASHINGTON — A NASA spacecraft is performing better than expected as it makes its closest approach to the sun this week.

Parker Solar Probe will pass 6.1 million kilometers from the sun at 6:53 a.m. Eastern Dec. 24, the closest approach to the sun by this or any other spacecraft. At the time of closest approach, the spacecraft will be traveling 191 kilometers per second.

The spacecraft launched in 2018 and used a series of gravity-assist flybys of Venus to lower its perihelion. The final Venus flyby, on Nov. 6, set up the spacecraft for this perihelion, the closest the spacecraft will fly to the sun on its mission.

“On Christmas Eve of this year, Parker Solar Probe will be the closest humanmade object ever to a star,” said Nour Rawafi, project scientist for the mission at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab (APL), during a media roundtable at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union Dec. 10. “We will be embracing a star.”

The spacecraft will be out of contact with the Earth during the flyby but is programmed to send a beacon signal on Dec. 27 to confirm that it made it through the flyby. The spacecraft will begin transmitting telemetry in early January, followed later in the month by science data.

Parker Solar Probe is shielded from the sun during its flybys by a thermal protection system. That heat shield is performing better than expected, said Betsy Congdon, lead engineer for the thermal protection system at APL. “We expect lower temperatures that we designed for and that we tested to,” she described at the briefing. “We overprepared.”

One reason for the lower temperatures was margin designed into the system. In addition, she noted that, in thermal testing on the ground before launch, the material appeared to get whiter at high temperatures, improving its performance, although at the time it wasn’t clear if that was a real effect or an artifact of testing. “We think that is real, that the coating is healing as it gets hotter.”

Other systems on the spacecraft are performing better on the system, Rawafi said. One example is the spacecraft’s solar panels, which are degrading less than predicted before launch. “The system is very healthy and it can go much further than we planned for.”

The mission, he said, is “opening our eyes on a reality about our star.” The spacecraft is providing scientists with key data on the solar wind and corona as it flies through it, as well as corona mass ejections from the sun. That is helping scientists learn more about the sun itself as well as other stars; it also provided data about Venus during its several gravity-assist flybys of the planet. “Parker Solar Probe is an exploration mission par excellence.”

Those observations are particularly useful as the sun goes through the maximum of its 11-year activity cycle, working in conjunction with data from other missions. “We have a tremendous opportunity with the heliophysics fleet to put together what Parker is seeing in tremendous detail” with data from those other missions, said Nicholeen Viall, a space scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “Parker is the key because it is so close.”

The spacecraft’s prime mission includes two more close approaches to the sun in 2025. Rawafi said the mission will seek a “bridge year” of funding in fiscal year 2026 to continue the mission until the next heliophysics senior review for fiscal year 2027.

The spacecraft can remain in its current orbit for a long time with little use of fuel to maintain it, he said. “The spacecraft can stay there for a long, long time.”