Key points

- Deterred by policy, technology and other factors in their country, some overseas travellers choose to receive IVF treatment in Australia.

- One fertility expert told SBS Mandarin that overseas patients seeking her services had “increased two to threefold” since the COVID-19 pandemic.

- One in every 18 babies in Australia are born through IVF, according to the UNSW’s annual IVF report published in 2023.

After a six-year, long-distance relationship with her partner in Australia, Olivia*, a Singaporean woman, decided it was time to start a family.

At 41, Olivia believed In Vitro Fertilisation (IVF) offered her the best chance of conception.

However, she quickly discovered that IVF was not an option for her in Singapore, where only married couples are eligible for IVF and the age limit for egg-freezing and subsequent use of these eggs is capped at 37.

So she flew to Sydney at the start of 2024 and started IVF treatment in Australia.

Olivia told SBS Mandarin that beyond her partner being based in Sydney, Australia’s genetic test technology, known as the Preimplantation Genetic Testing for Aneuploidy (PGT-A) test, was a key factor in her decision.

The PGT-A test identifies whether embryos are “genetically normal” before being transferred to the uterus, which Olivia said was especially critical for women over 40.

“If you don’t test it, you just put it [the embryo] in your womb, (even) if it’s abnormal … And what will happen is that you most likely will miscarry,” she said.

In Singapore, IVF is only accessible to married couples. Credit: Yong Teck Lim/AP

According to by the University of New South Wales (UNSW), one in every 18 babies in Australia are born through IVF, with more than one in three women (37.1 per cent) carrying a baby to term after just one cycle of IVF.

During her first IVF cycle in May, Olivia retrieved four embryos, but all were found to be “genetically abnormal” after undergoing PGT-A testing.

I spent over $20,000 and I went through two and half weeks of pain and my results were bad. So, I was very, very upset.

Olivia*

In July, Olivia underwent her second cycle of IVF. This time, she obtained seven embryos and three were deemed viable.

“I was very relieved because at least of these three, hopefully, if all goes well, I can at least have one child.”

Olivia is one of many international patients treated by Sydney-based fertility specialist and gynaecologist Dr Cheryl Phua this year.

Phua told SBS Mandarin that the number of overseas patients seeking her services had “increased two to threefold” since the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly inquiries from China.

“Before COVID, we would see one or two overseas patients per month, mostly from Singapore, with perhaps one or two from China,” she said.

“Now, I see one or two patients from China every week, along with many others from Singapore, Malaysia and other southeast Asian countries.”

Sydney fertility specialist and gynaecologist Dr Cheryl Phua said she had received more overseas patients since the end of the pandemic. Source: Supplied

She explained that most of her Chinese patients were unmarried women looking to freeze their eggs or undergo IVF using donor sperm.

“We also have many same-sex couples who can’t access IVF treatment in China. They come here to use one partner’s eggs and select a sperm donor of their choice,” she said.

Similar to Singapore, access to fertility treatments in China is restricted. Under Chinese law, unmarried women are prohibited from undergoing procedures such as egg-freezing or IVF.

This restriction has driven some Chinese women to seek fertility services abroad.

Melbourne resident Rui Shen told SBS Mandarin that she believed that this regulation was “unreasonable”.

“China has lifted its three-child policy, yet unmarried women still aren’t allowed to freeze their eggs. I think this contradicts its policy goals,” she said.

Rui Shen got her eggs frozen in May in Melbourne. Credit: Supplied

The 34-year-old has lived in Melbourne for seven years. In May, she decided to freeze her eggs to preserve her reproductive rights while not rushing to have a baby.

“I would like to start a family with a responsible person that I like and raise a child together, but I don’t know when I will meet such a person,” she said.

“I don’t want to reach my 60s, realise I want a child and find that it’s no longer possible … It [freezing my eggs] gives me a sense of psychological comfort.”

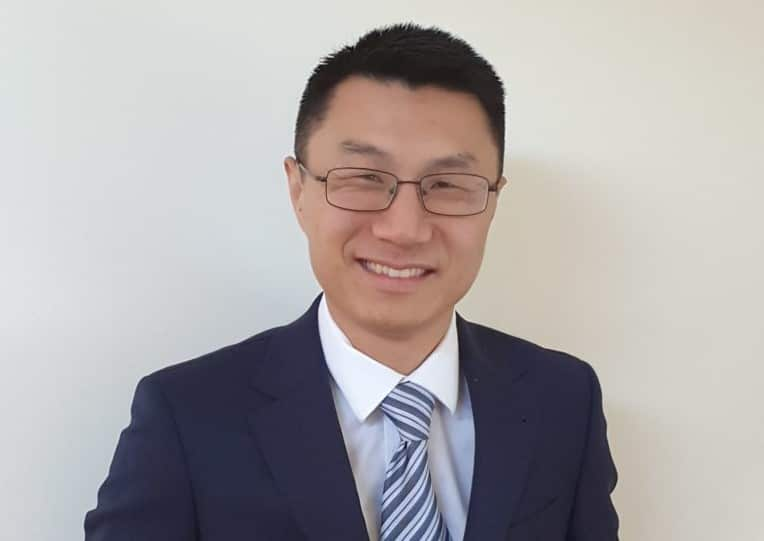

Sydney-based fertility specialist and obstetrician Dr Charley Zheng said that Australia’s pleasant climate and multicultural atmosphere offered additional appeal to overseas patients, helping them feel more at ease during treatment preparations.

However, he pointed out that the PGT-A test, which Olivia viewed as essential, was not mandatory and came with certain limitations.

Sydney-based fertility specialist and obstetrician Dr Charley Zheng says the PGT- A test has some limitations. Source: Supplied

He explained that the PGT-A was an “invasive test” involving the use of a laser to create a small opening in the outer layer of a five-day-old blastocyst (an early stage of embryo development that occurs approximately five to six days after fertilisation), from which five to 10 cells were extracted for chromosomal analysis.

If an embryo was identified as normal through genetic testing, it did not guarantee the child would be free of health issues, he added.

“It does not reduce (the incidence of) other issues such as genetic disorders (unless specifically tested for), structural abnormalities, polygenetic disorders (such as autism), or birth/pregnancy-related disorders,” he said.

After completing her second IVF cycle in July, Olivia returned to Singapore.

She plans to return to Australia early next year for the embryo transfer.

“If I can, I will try my best to have children because I think It’s nice to have a family with someone you love and then raise your own kids,” she said.

Information provided in the article is generic in nature and readers should consult with medical professionals for specific information.