The moment Susan was told her four grandchildren would be sent to a youth home is etched in her memory.

“There were two detectives and two police officers, and I just broke,” the Wirangu woman from South Australia’s far west coast says.

It was mid-2023 and the children had been living with Susan whose name we’ve changed, for two months in a remote Aboriginal community, about 10 hours drive from Adelaide.

Authorities from the state’s Department for Child Protection (DCP) had previously removed the children from their parents, citing issues relating to illicit drug use.

Grandmother Susan had stepped up.

“They’re my blood,” she tells SBS News.

“I will step up, I’ll look after them.”

Due to South Australian law, the identities of Susan’s grandchildren cannot be published. Source: Supplied

At the DCP’s request, Susan found a new house to live in with the children and started the application process to become their kinship carer.

But in September, she was called into a meeting at the local DCP office where she was told she was a ‘prohibited person’, and her grandchildren would not be going home with her.

“The two-year-old girl froze,” Susan says, adding that the three boys bowled her over in tears.

We just shook and cried. I knew that day that I lost my grandchildren that I had a fight on my hands.

‘Sleep with one eye open’

South Australian law requires family carers to pass working with children and prohibited person checks, which are conducted by the DCP’s screening unit.

While the intention is to keep children safe, there is growing concern the process rules out appropriate family carers because it nets irrelevant and historic records, including reports that haven’t been substantiated.

A following South Australia’s two-year public inquiry into the removal and placement of Aboriginal children found that the requirement for prospective family carers to have a clear child protection record was limiting. It notes: “In practice, families are often not provided with an explanation for their non-acceptance as carers and given limited opportunities to address the concerns or correct any inaccurate information.”

Susan is still unsure why she was deemed a prohibited person: a freedom of information request sent to the DCP via her legal representative failed to clarify the decision. She says she had some interactions with police while her daughter and grandchildren were living with her in early 2023.

Susan recalls the “acting boss” at the DCP office telling her she was “aggressive”.

“[They said] I could not look after them; I was incapable of having them in my care. I wasn’t ideal for them,” she tells SBS News.

The DCP would later reverse its decision, returning the children to Susan with a glowing report of the home and loving care she provided.

But nothing can take away from the trauma endured by the family during that period of separation.

Susan still doesn’t know the exact reasons she was deemed a ‘prohibited person’ by the Department for Child Protection. Source: Supplied

The four siblings — then aged between two and 11 — were sent to a youth home in a bigger town, hundreds of kilometres from their community, where they would stay for the next two-and-a-half months.

“I saw an eleven-year-old child turn into a man that day,” Susan recalls, explaining how she entrusted the care of the three younger siblings to their big brother.

Traumatised by her own childhood experiences “in the system”, Susan was terrified about what might lay ahead for her grandchildren as she said goodbye to them at the DCP’s office.

Susan was taken from a beach as a baby and spent much of her childhood in state care.

“If you’re in the same house together, always sleep with one eye open, one eye closed,” she recalls telling her eldest grandson.

They put the four kids together in one house, and they all slept in one room on a double bed.

“And he did that, he slept with one eye open, one eye closed to protect his siblings.”

Approaching Stolen Generation numbers

During the it’s estimated between one in three and one in 10 from their families.

Advocates in South Australia say the number of children being removed today is fast approaching those historic levels.

The state’s commissioner for Aboriginal children and young people, April Lawrie, has been calling for urgent action to address what she says are “unnecessary” removals, based on “institutionally racist” decision-making.

South Australian commissioner for Aboriginal children and young people April Lawrie (pictured) launched the final report for the inquiry into the removal and placement of Aboriginal children in June of this year. Source: Supplied

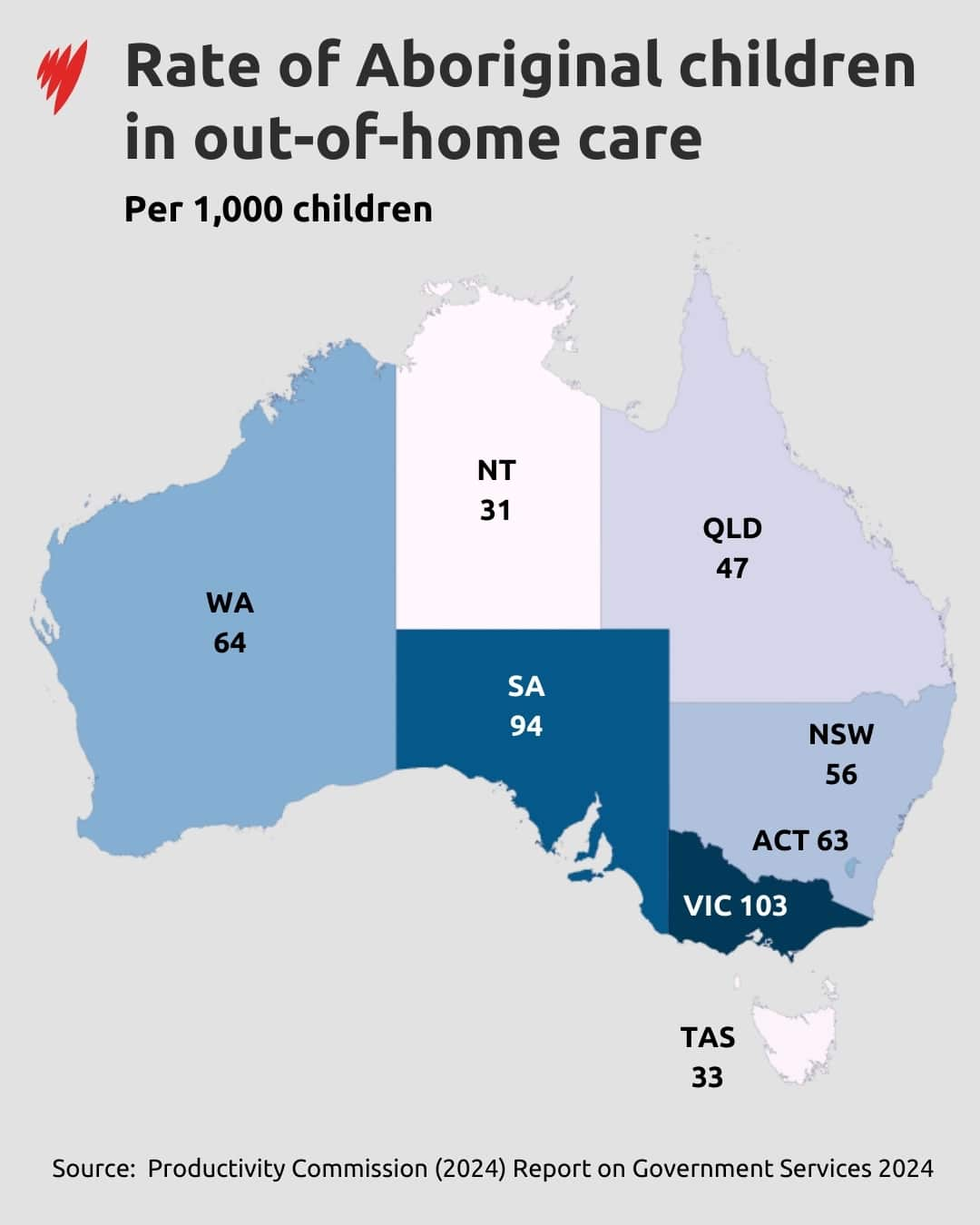

“If we don’t curtail the rates of Aboriginal child removals, we can expect in seven years — by 2031 — that 14 out of every hundred Aboriginal children here in South Australia will be in state care,” she says.

According to findings from the public inquiry, which Lawrie commissioned, nearly one in 10 Aboriginal children are currently in state care.

In its final report Holding on to Our Future, which includes 48 findings and 32 recommendations, the inquiry found that working with children and prohibited person checks were a key barrier to keeping families together.

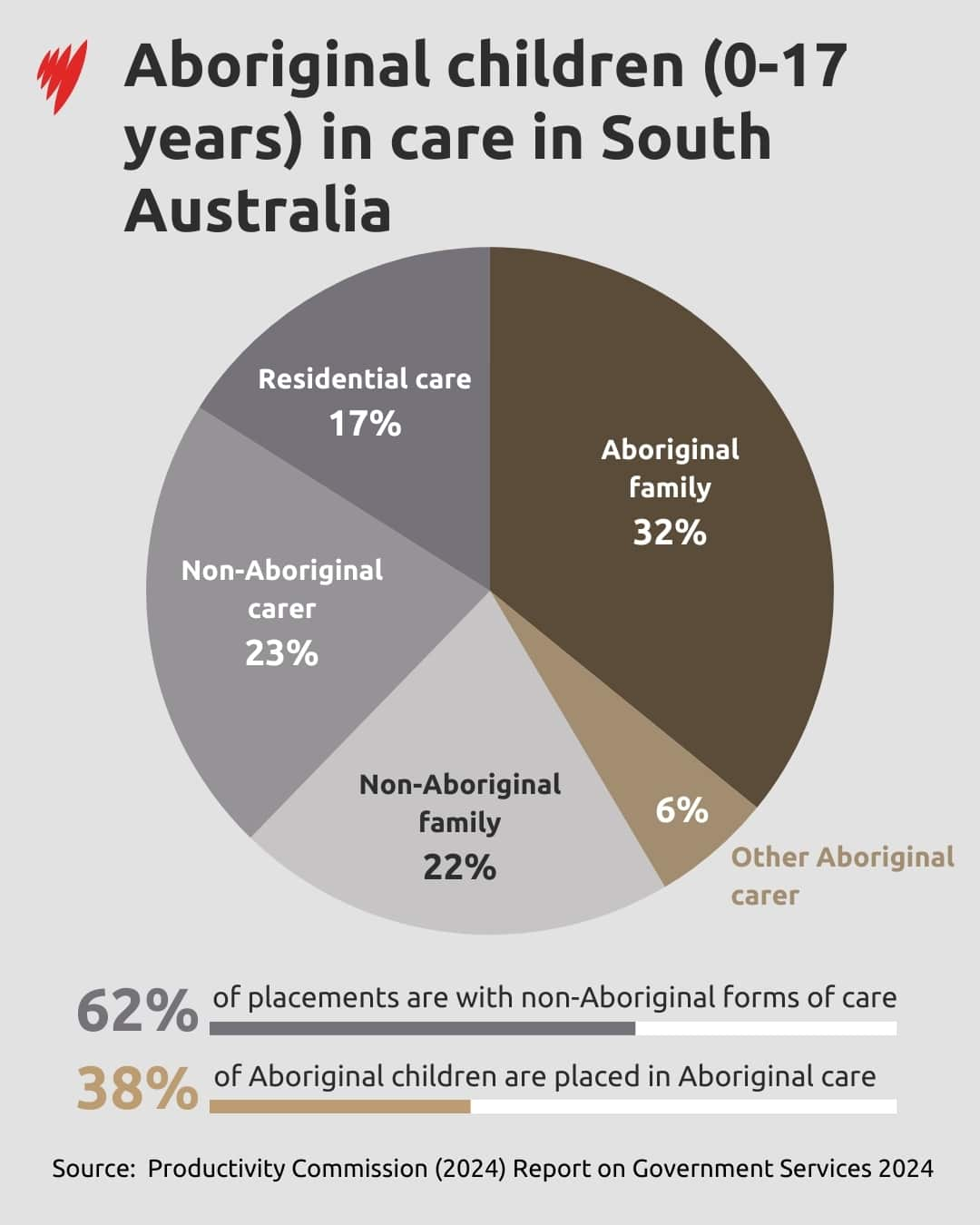

Only 30 per cent of children who are removed are placed with kinship carers in South Australia, and just six per cent are placed with other Indigenous families.

The majority of Aboriginal children in state care are not placed with Aboriginal carers. Source: SBS News

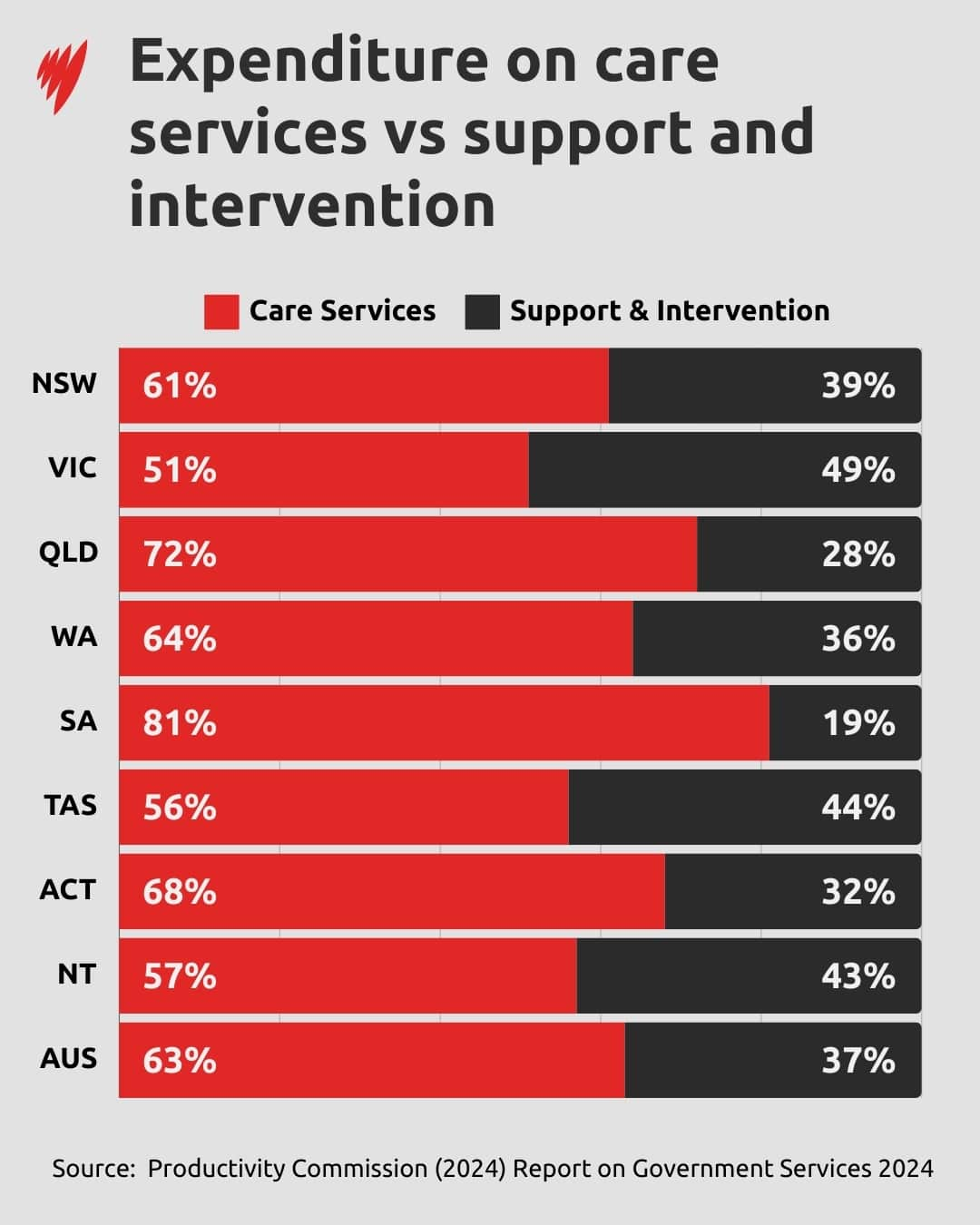

The report also shows South Australia has the lowest rate of family reunification and spends significantly more on care — and less on preventative measures — as compared with any other Australian jurisdiction.

Susan’s story isn’t included in the report, but Lawrie says it resonates with the experience of many Aboriginal families.

“[Susan] as a grandmother — who is probably the most suitable person and who loves her grandchildren — was alienated from her grandchildren and the process,” Lawrie says.

For all sorts of wrong reasons, she was considered an unsafe person.

According to Lawrie, a lack of input from Aboriginal organisations, extended family and the wider community was evident in Susan’s case, and others she has reviewed.

“The system needs to understand and acknowledge that people change; that people’s stories are different today from what they were in the past.

“The things that actually make you a good parent or good grandparent need to be understood.”

Proportionately, South Australia spends the least on support and intervention services. Source: SBS News

Irrelevant and inappropriate assessments

Wakwakurna Kanyini is a new community-controlled peak body based in South Australia, which represents Aboriginal children and their families and advocates for their continued connection to culture and community.

Its CEO Ashum Owen says the issues preventing most family members from progressing through kinship carer assessments are “mostly irrelevant to their ability to provide safe and appropriate care”.

Ashum Owen (left) and Sandra Miller are among Indigenous leaders calling for child protection reforms. Source: Supplied

The Kaurna, Narungga and Ngarrindjeri woman worked on the state inquiry and says the process failed to provide procedural fairness to Aboriginal carers.

“When you take into consideration the disproportional criminalisation of Aboriginal people, the levels of racial profiling by police, and the intergenerational child protection contact, these initial checks feed into culturally biased and inappropriate assessments,” Owen says.

“Particularly that the Department for Child Protection undertake criminal history checks and child protection checks without consent and prior to applications of Aboriginal kinship carers.”

In a statement, a spokesperson for the DCP told SBS News it undertakes working with children checks (WWCC) with the permission of prospective carers, adding that it “checks about any other previous notifications to Child Protection. It does not conduct its own criminal history checks on prospective carers”.

“A WWCC is one of the tools used to assess whether a carer or prospective carer could pose a risk to children’s safety, and the Department for Human Services Screening Unit may consider a person’s criminal history as part of this process,” the spokesperson said.

Queensland recently became the first state to remove its working with children certificate requirements for family carers.

A Queensland found they relied on “irrelevant information, over-policing and subjective assessments” and disproportionately impacted Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Removing working with children checks for family carers is an important step to improving procedural fairness says Owen.

“Through this initial vetting process, they can eliminate many potential Aboriginal family members, [which] leads to Aboriginal children ending up in placements in non-Aboriginal foster care or residential care, ” she says.

The Child Placement Principle

The Holding on to Our Future report offers a damning assessment of the South Australian government’s implementation of policies developed over generations and aimed at keeping Aboriginal children safe and connected to their families and culture.

Its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle policy holds that every attempt should be made to place a child with his or her family and removal should only be considered as a last resort, in consultation with a child’s extended family and community.

Out-of-home care rates among Aboriginal children are highest in South Australia and Victoria. Source: SBS News

It was developed by Aboriginal leaders in the 1970s to avoid future Stolen Generations and sets out an Aboriginal child’s right to culture, family and community, as well as safety.

In the 1980s and 1990s, it was progressively adopted into legislation — but some advocates say it has been misunderstood.

“Unfortunately, the way in which the legislation holds the principle and the paramount of safety, it’s almost like they’re two separate conditions,” Lawrie says.

When, in fact, the principle — or the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle — is about safety within family, community and culture.

“When the system starts just focusing on one single issue and does not have this holistic view about what’s in the best interest[s] of the child, or the children in this case, then we see things go very wrong.”

Lawrie’s inquiry has made 32 recommendations to fully implement the Child Placement Principle in a proactive way.

The South Australian government has yet to respond to the inquiry.

A spokesperson told SBS News in a statement the government is taking “the appropriate time” to consider the recommendations before issuing a response.

“It is vital that both systems and staff across the child protection and family support system recognise the importance of Aboriginal-led decision-making and culturally appropriate engagement and practice,” the spokesperson said.

The interim chair of the new community-led Aboriginal peak body Sandra Miller says the child placement principle had been implemented decades ago, but not abided by.

“The majority of our children are with non-Aboriginal families,” Miller says.

She hopes the August launch of Wakwakurna Kanyini will help improve the situation and become the community voice she’s been advocating for for more than 40 years.

I’m hoping the organisation can one day be its own service provider where Aboriginal voices will be heard and we can work with individuals and families.

“To, if you like, mend the broken families that we have out there, and ensure our children get returned to us.”

‘It’s Nanna waiting for you’

The day Susan’s grandchildren were returned is also etched in her memory. She and a cousin drove four hours to the youth home where DCP staff met them and released the children one by one from a parked car.

“It’s Nanna [Susan] waiting for you,” she says in a video recording of the moment.

The oldest sibling runs to her. But the two-year-old is hesitant.

“That’s what broke my heart,” she says.

“The little one just looked at me and cried like she didn’t know who I was.”

Susan is relieved to have her grandkids back in her care. Source: Supplied

After losing the children, Susan sought legal advice and reached out to Lawrie via a family contact.

The children were returned following a letter of advocacy from the commissioner and the return of the permanent manager to the local DCP office.

“It could have been avoided if the original boss was in the office at the time, but they had the fly-in-fly-outs … and they came in and made decisions,” she says.

“They didn’t know my background, they just had reports more or less.”

SBS News contacted the Department for Child Protection but it declined to respond, saying it cannot comment on individual cases.

Susan says she is relieved the children are safe.

“I’m just glad they are with me. I just don’t have to look over my back anymore.”