TAMPA, Fla. — The British subsidiary of Japan’s Astroscale is preparing for a critical design review early next year of a servicer that will attempt to remove a OneWeb broadband satellite from low Earth orbit (LEO) in 2026.

“We’ve completed a lot of the subsystem level developments and we’ve bought a lot of the flight hardware,” Astroscale UK managing director Nick Shave said in an interview.

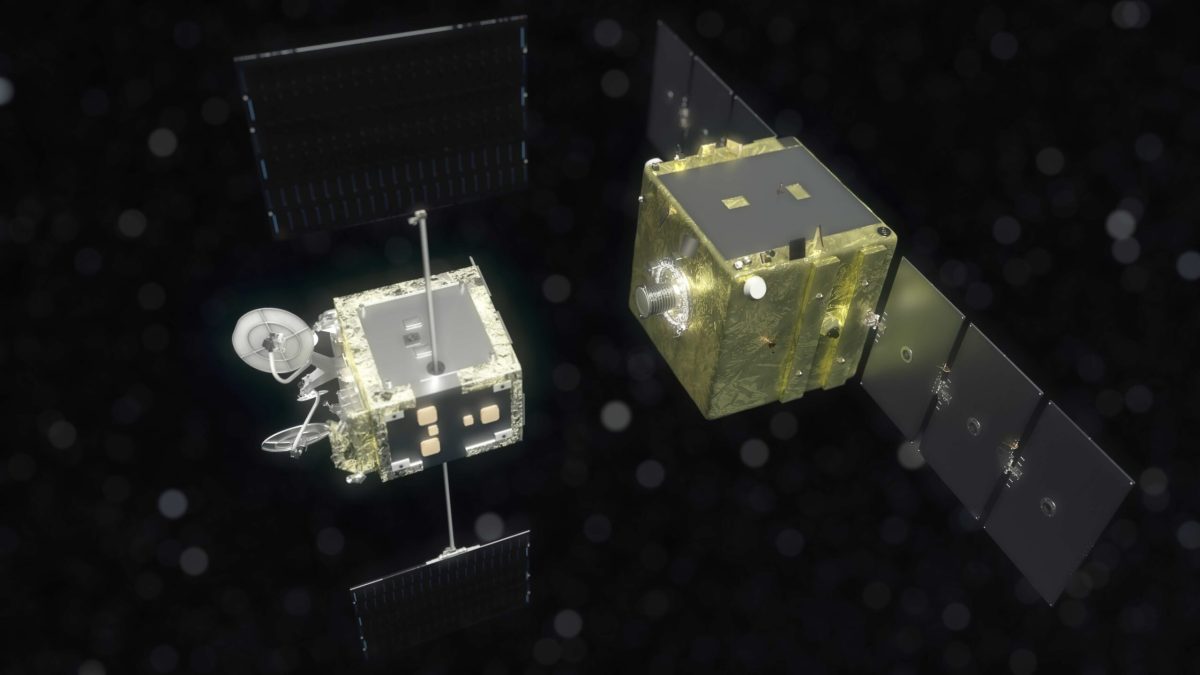

The 500-kilogram servicer for the ELSA-M program, or End-of-Life Services by Astroscale-Multiple, is currently in a “flatsat” phase where its various components are laid out on a clean room table for testing and checkout.

“GNC [guidance, navigation, and control] on the program is quite complex, as you can imagine,” Shave said. “We’re doing a lot of Rendezvous and Proximity Operations activities and a lot of it is novel.”

Astroscale has a dedicated team of 40 people in the United Kingdom working on finalizing the flight software ELSA-M would use to approach and capture a OneWeb spacecraft that is no longer operating, later releasing it on course to burn up in the Earth’s atmosphere.

The servicer would use a capture mechanism compatible with magnetic docking plates on most of U.K.-based OneWeb’s more than 600 satellites.

The demonstration is a precursor to a commercial de-orbit business Astroscale hopes to start offering toward the end of this decade, alongside other ventures such as Switzerland’s ClearSpace and Starfish of the United States.

After finalizing algorithms and completing the critical design review, Astroscale plans to integrate ELSA-M subsystems during 2025 for a launch Shave said would likely occur in the second quarter of 2026.

Astroscale had aimed to conduct the demo mission this year. However, OneWeb, which was sold to French fleet operator Eutelsat in 2023, only recently received a contract as part of its public-private partnership with the European Space Agency to advance the mission.

The ELSA-M demonstration brings together Astroscale, Eutelsat’s OneWeb, the UK Space Agency, and European Space Agency to help make space more sustainable.“No company or nation has captured a spacecraft in orbit and removed it from orbit commercially,” Shave said.

While the UK Space Agency and European Space Agency have provided around $35 million in funds, he said Astroscale is financing “well over 50%” of the mission.

ELSA-M builds on ELSA-d, or End-of-Life Services by Astroscale-demonstration, which released, recaptured, and released again a tiny LEO satellite in 2021.

The ELSA-d servicer, about a third of ELSA-M’s size, later lost half its thrusters, making it unable to recapture the client a second time for a controlled descent that would have seen them jointly burn up in the Earth’s atmosphere. Instead, the client satellite was left at about 500 kilometers altitude to decay naturally over the next several years as it gradually falls back to Earth.

OneWeb satellites operate at 1,200 kilometers and would take around 2,000 years to reenter the atmosphere without intervention.

Unlike the ELSA-M mission, the ELSA-d servicer was also launched alongside the simulated piece of debris provided by SSTL.

“This is the first capture of another full satellite that wasn’t built by us and owned by a different entity,” Shave said.

Gearing up for launch

Astroscale is in talks with multiple launch companies for a ride to around 550 kilometers altitude, from where ELSA-M would use onboard electric propulsion to climb to OneWeb’s operational orbit.

Shave said the company is still considering whether to book a dedicated launch or join at least one more co-passenger to orbit to save costs.

SpaceX’s “Falcon 9 could take us,” he said. “They’ve got configurations for doing things like this with Starlink or whatever underneath. That’s one option.”

However, a dedicated launch would place the servicer at OneWeb’s 97-degree inclination.

“If we didn’t have a dedicated launch, we’d have to spend more fuel doing an inclination change, potentially, so it’s a trade-off that we’re working through,” he said.

The mission

Astroscale and OneWeb are still deciding which satellite to de-orbit in a mission that is projected to take a few months to complete following launch.

According to Shave, the companies could wait until launch day to pick a target for ELSA-M.

“We carry enough fuel to do three de-orbits,” he said. “That’s the mission design [and] we’ve designed the mission around a couple of scenarios which are aligned with potential target spacecraft in their constellation.”

OneWeb declined to comment.

Shave said Astroscale is considering a variety of other missions before ultimately de-orbiting the servicer, including using it for space situational awareness.

“We’ll have a suite of sensors as needed for the mission that could help in a number of areas,” he said.

“There are other projects that we’re looking at in the space traffic management area,” he continued, including collision avoidance demonstrations.

“We haven’t definitively decided what we do yet,” he added, “the key thing obviously is to get the build complete and get into orbit.”

Meanwhile, a separate Astroscale spacecraft is currently inspecting a discarded upper stage of a Japanese H-2A rocket, as part of the Active Debris Removal by Astroscale-Japan (ADRAS-J) mission for Japan’s space agency. The company recently finalized a contract to remove the rocket body from LEO with a servicer equipped with a robotic arm.

Astroscale is also in the running for a UK Space Agency contract for a mission to remove two spacecraft from LEO in the next few years with their servicer spacecraft COSMIC, or Cleaning Outer Space Mission through Innovative Capture.