Shokrollah Jebeli had been living in Australia for more than three decades when he returned to his native Iran. He was in his 60s and, despite living happily in Sydney with his family since 1976, decided to return to his hometown of Tehran in 2007 to live out his elderly years.

It’s a decision that ultimately cost him his life.

In early 2020, Jebeli was detained by Iranian authorities and sent to Tehran’s notorious Evin prison, where he was held for more than two years on charges relating to two separate financial disputes. His family maintain the charges were false.

In March 2022, the then 83-year-old Iranian-Australian dual citizen was found dead in his cell after falling critically ill.

Shokrollah Jebeli (pictured) migrated to Australia in 1976. Credit: Supplied

His son Peyman Jebeli, who had worked tirelessly to raise money to fund his father’s legal case from Australia, says Iranian authorities denied him access to vital medication and subjected him to torture by deliberately and .

“None of it makes sense,” he tells SBS News.

There’s no doubt in my mind that my father was innocent, and he died innocently at the hands of people who wanted blood for money.

Peyman Jebeli

Shokrollah and his family had been fighting to overturn the four-and-a-half-year sentence handed down over one of the two financial disputes brought against him prior to his death — the second case was ongoing.

According to Amnesty International, the octogenarian’s trial was unfair: the judge presiding over his case denied him a lawyer of his own choosing and refused to consider evidence that could help him.

Shokrollah’s son says he will never forget the phone call he received in early 2020 that brought the news his father had been arrested.

“I was just stunned,” he says.

“You can’t sleep. You feel like you shouldn’t be living a normal life when someone who’s so dear to you and close to you is experiencing terrible pain.”

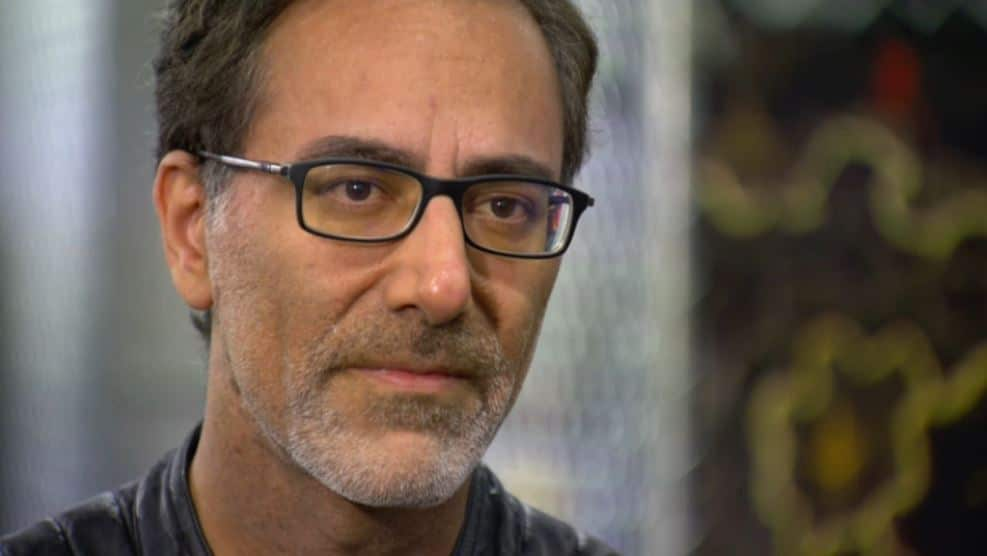

Peyman Jebeli says his father’s treatment is tantamount to torture. Credit: SBS

‘Life and death situation’

While his father was in prison, Jebeli says multiple attempts were made by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) to have him released via the Australian embassy in Tehran, but it was denied consular access.

According to DFAT, Iranian authorities also refused to accept Shokrollah’s Australian citizenship.

Peyman Jebeli says DFAT’s efforts came “way too late” — only a couple of months before his father’s death.

“I initially contacted the Australian government and the response was that he’s not recognised as an Australian citizen by the Iranian authorities. Therefore, Australia can do very little,” he says.

“I think [the Australian government] thinks they did all they could. But, when it comes down to the very basic element of it, I think it’s just a matter of recognising that it’s a life and death situation.”

It’s not for another country to decide whether I’m Australian or my father’s Australian. It’s for Australia to make that decision.

Peyman Jebeli

At least two Australians detained in Iran

Shokrollah’s is not an isolated case.

SBS News understands that there are at least two Australian citizens currently being detained in Iran.

In a statement, DFAT did not confirm the claim but said the department will “continue to work with partners to highlight the harsh impacts on individuals and their families and to work together to help mitigate those impacts”.

One source, who has requested anonymity, claims that one of the individuals detained in Iran is an Australian man with dual citizenship, who was arrested in July 2022 and sentenced to several years in prison.

Kylie Moore-Gilbert — director of the Australian Wrongful and Arbitrary Detention Alliance and — has been working with the families of detainees who are in a similar position to the one in which she found herself in 2018.

“It’s very different when we talk about dual nationals because these people are Australian citizens, but they might have close family members and other property and assets inside Iran,” Moore-Gilbert says.

“There’s also an aspect of transnational repression involved, and we know that Iranian agents are operating here on Australian soil.”

SBS News approached the Iranian embassy in Canberra for comment, but they did not respond by the deadline.

A spokesperson for DFAT said in a statement: “Australia stands resolutely against the practice of arbitrary detention, arrest and sentencing wherever it may occur, including when used for diplomatic leverage.”

British-Australian academic Kylie Moore-Gilbert has been working with the families of Australians held in arbitrary detention. Credit: SBS

Hostage diplomacy as a ‘business model’

Moore-Gilbert has experienced firsthand how ruthless Iranian authorities can be when it comes to detention.

Like Shokrollah, — including at Evin — after being sentenced to serve 10 years on espionage charges.

She has always denied those charges.

“Iran is one of the more prolific practitioners of hostage diplomacy, including of Australian citizens; also wrongful and politically motivated detentions, often targeting dual nationals — including dual citizens of Iran and Australia,” she tells SBS News.

They have suspicions, they pick you up, and then they see value in transforming you into a hostage after the fact.

Kylie Moore-Gilbert

Some experts describe these types of detentions in Iran as hostage diplomacy, which is the act of taking hostages for diplomatic purposes.

The most recent example was in June when in exchange for two Swedish citizens: European Union diplomat Johan Floderus and dual-national Saeed Azizi, who were freed by Iran and flown back to Sweden.

“Iran has turned hostage diplomacy into something of a business model. It’s benefited massively from a number of countries,” Moore-Gilbert says.

“I’m one example of that: three convicted terrorists were released from prison in Thailand in exchange for me.”

In 2020, following the British-Australian academic’s release, .

After the release of both parties, then-prime minister Scott Morrison declined to comment on whether a swap had occurred but confirmed no Australian prisoners had been released.

“I would like to pay tribute to DFAT and the Australian embassy in Tehran: They did a wonderful job in securing my release under very complicated circumstances,” Moore-Gilbert says.

“That being said, there are a number of issues with Australia’s current system in a more structural fashion.”

Senate inquiry launched

Cases of arbitrary detention, such as Moore-Gilbert’s and Jebeli’s, have spurred a Senate inquiry into the wrongful detention of Australians overseas.

Astrid Habi, an executive member of not-for-profit organisation Australians Detained Abroad (ADA), tells SBS News the inquiry is “a really important step”.

“It provides an opportunity for the government to establish a foundational set of principles in relation to how Australians who are detained abroad are dealt with,” Habi says.

The focus of the inquiry includes reviewing Australia’s policy framework for deterring arbitrary detention, its case management processes and communication with and support for Australians who are wrongfully detained overseas and their families.

According to Liberal senator Claire Chandler, who is chairing the inquiry, a lack of support for families has been a common criticism raised during the early stages of the inquiry.

“We’ve heard from witnesses through the Senate inquiry — family members of Australians who were detained overseas — and they spoke about how scary it was when they weren’t getting regular updates from the government,” the Opposition assistant foreign affairs spokesperson explains.

Peyman Jebeli echoes that sentiment.

“When you’re in the dark, it’s very hard to understand what you are feeling; you feel a myriad of emotions,” he says.

You feel angry because you feel abandoned.

Peyman Jebeli

As part of the inquiry, some advocates are calling for a specific framework to be established in relation to hostage diplomacy in Australia, including ADA.

Speaking on behalf of the organisation, Habi says: “At the moment, what we see is a fairly ad hoc response … What we hope is that there’s a transparent, easily accessible set of principles so people know what DFAT can do, what the government can do, and what they can’t do or what they won’t do.”

“It really just helps build a framework for how we deal with any Australian or permanent resident who is detained overseas.”

There are also calls for a special envoy for Australians wrongfully detained abroad, which would be similar to the United States special presidential envoy for hostage affairs.

Established in 2015, the envoy works to secure the freedom of US national hostages and wrongful detainees held abroad and has helped secure the release of American citizens in Afghanistan, Iran, Myanmar, Nigeria, Russia, Syria, and Venezuela in recent years.

A young Shokrollah Jebeli, pictured with his son Peyman in Sydney. Credit: Supplied

Peyman Jebeli says an equivalent Australian special envoy could “save lives”.

“If there was something like that in place and there was a special envoy in Australia, I think my father would be alive right now.”

He is particularly concerned for Iranian expats wanting to visit their homeland, like his father.

“If he walked into this room, he would breathe life into the room. That’s the kind of person he was so charismatic.

“I’m sure there are people [like him] going to the airport right now and going to Iran to visit family.

“How are they meant to know that something like that’s going to [happen] or certain people are going to pinpoint them or take advantage of them?”