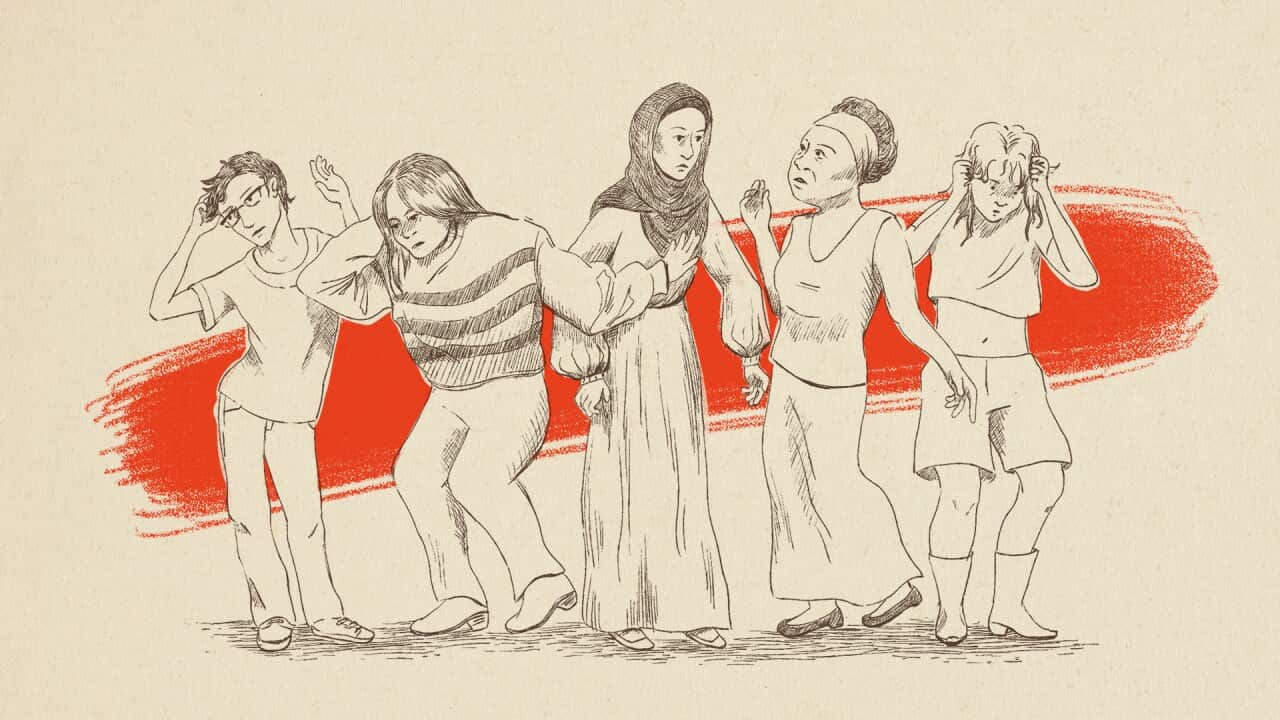

For some women, trans and gender diverse people, dismissal of pain and symptoms can be a common experience.

After having surgery on her foot, Tracey, 63, says she felt dismissed by her GP.

“I was told I was a hypochondriac because he couldn’t work out where the pain was coming from,” she told SBS News.

“I know where it was coming from, so I actually left crying saying ‘I’ll just put up with the pain’.”

Younger women are reporting similar experiences, including Eleni, 32, who says she often feels uncomfortable visiting doctors.

“I just don’t think that I left feeling heard or really had a solution to my problem,” she said of one visit.

These experiences are explored in which looks at medical misogyny and discrimination in our health system — and why women, trans and gender diverse people are more likely to be dismissed.

‘Hysterical’ is a term that dates back to ancient times, and was used to pathologise women and their experiences.

But what is hysteria and where did it originate?

The history of hysteria

The term hysteria was first coined by Hippocrates in the 5th century BC and used by other ancient Greek and Roman physicians and philosophers such as Plato.

Jane Ussher is a professor in women’s health psychology at Western Sydney University and has written extensively on the intersection of gender and health care.

She said there were discussions of hysteria dating back to ancient Greek and Roman times.

“It was believed that the woman’s womb travelled around the body, and all sorts of ailments and ills were blamed on the womb,” she said, adding these ranged from “psychological phases a woman might experience to any sort of physical changes”.

Ussher said this was even visible in early medical manuscripts, where there were “pictures of the womb that was believed to travel”.

How hysteria became a psychiatric issue

It wasn’t until the 19th century that hysteria became a psychiatric issue, Ussher said.

Prominent psychiatrists and psychoanalysts, including Sigmund Freud, categorised it as a psychological issue predominantly associated with women.

“What we saw there was really the reproductive organs being seen as the cause of women’s, I would say, ‘madness and badness’,” Ussher said.

Professor Jane Ussher said there were discussions of hysteria going back to Greek and Roman times when it was believed that the woman’s womb travelled around the body. Credit: SBS

She said women who were discontent with their lives, or who didn’t want to be confined to the roles of wives and mothers, were often positioned as mad and “locked in asylums”.

“Some people have argued that hysteria was a catch-all diagnosis that really allowed any sort of symptom that was negative, and was seen as not fitting the particular very narrow version of femininity.”

How is it relevant today?

The hysteria diagnosis appeared in and was finally removed in 1980.

But for women today, issues around the dismissal of pain and symptoms continue.

The medical history of hysteria inspired author Katerina Bryant’s 2020 memoir which shares its title with the diagnostic label.

Bryant, 30, started writing the book at the same time she was struggling to receive answers about what she was experiencing in the health system.

“I sought historical narratives of other women during their times of distress and illness, all centring around the experience of hysteria,” Bryant said.

The medical history of hysteria inspired author Katerina Bryant’s memoir. Credit: SBS

She says she was experiencing what is now categorised as functional neurological disorder or non-epileptic seizures.

This included a series of sensory processing issues, including body numbness, simple visual hallucinations, and not being able to speak for certain periods of time.

The one place she could find solidarity was among the women identified through her research into hysteria.

“Finding all these women’s stories who were connected to hysteria really felt like a community when I wasn’t able to have one,” Bryant said.

“Often, or almost always, the onus is on the individual experiencing symptoms and distress to find answers.”

To learn more about medical misogyny and discrimination in our health system, such as dismissal of pain and barriers around sexual and reproductive health, listen to the