Brad Setser challenges the notion that globalization has turned to “slowbalization”. But what are the characteristics of globalization?

Slobalization!?

Trump Flashback

Dangerous Myths of Deglobalization

Last week, a Bloomberg columnist piled on, concluding that “global trade and finance are fragmenting into rival and increasingly hostile blocs, one centered on China and extending into the global South and another around the United States and other Western countries.”

But there is a problem with the assumption that deglobalization is a fact on the ground: the data does not fully back it up. As evidence of continuing deglobalization, observers often cite phenomena such as the United States’ reluctance to establish new free-trade deals, the debilitation of the dispute-settlement system overseen by the World Trade Organization (WTO), the proliferation of new national measures restricting trade, and declines in both short- and long-term capital flows from their past peaks. The COVID-19 pandemic certainly did reveal that economic interdependence carries risks, and the efforts Russia has made since 2022 to use its natural gas pipelines to influence the G-7’s response to its invasion of Ukraine—as well as the many sanctions the G-7 has imposed to try to weaken Russia’s economy—have highlighted the vulnerabilities that can arise when countries trade across geopolitical divides. But a closer look at economic data shows that even though governments have increasingly adopted policies aimed at strengthening their own resilience, the world economy is still evolving to become more, not less, globalized in key ways—and more dependent on Chinese supply in particular.

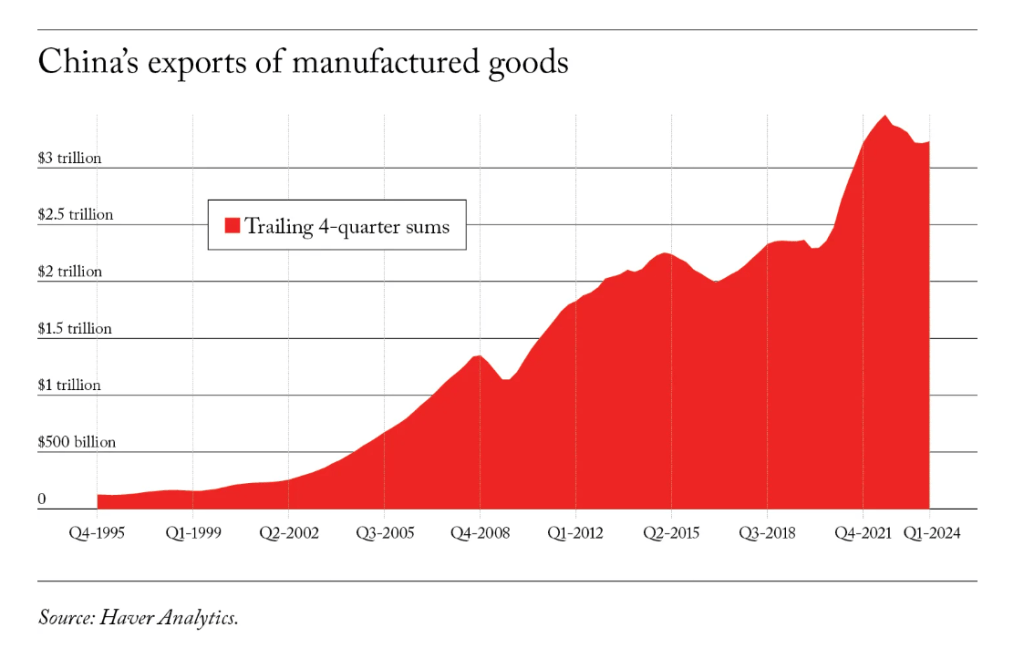

Global trade surged during the pandemic, and the world’s trade with China accelerated rather than slowed. A pandemic-era shift toward goods and away from services partly accounts for the acceleration. But the growth in trade with China also reflects the fact that China is simply producing things—high-tech exports such as electric vehicles, wind turbines, solar panels, and vital electronic and battery components—at a price point few can match. Between 2019 and 2023, China’s manufacturing surplus rose by about a percentage point of global GDP; it is now far larger than the surpluses run by Germany and Japan, the world’s other manufacturing powerhouses.

The idea that the world’s economy is deglobalizing took hold after the 2016 election of U.S. President Donald Trump. In his rhetoric, Trump repudiated the post–World War II bipartisan consensus around the value of free trade. And he also made some genuine policy shifts: pulling out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement to tighten the rules of origin for the trade of automobiles, and introducing tariffs on roughly three-fifths of the trade between the United States and China.

But globalization has deep roots by now, and such bilateral trade policies did little to change its fundamental trajectory. New trade deals and tariff programs always get a lot of ink. In reality, the changes in tariff rates in modern free-trade deals tend to be small, as most tariffs are already low or zero. Countries lacking preferential access to the U.S. market can still do incredibly well with the WTO’s standard trade terms. In fact, U.S. imports from Southeast Asia have soared in the past half dozen years. The Southeast Asian members of the TPP increased their exports to the United States much more rapidly after Trump withdrew from the TPP than they had been able to before.

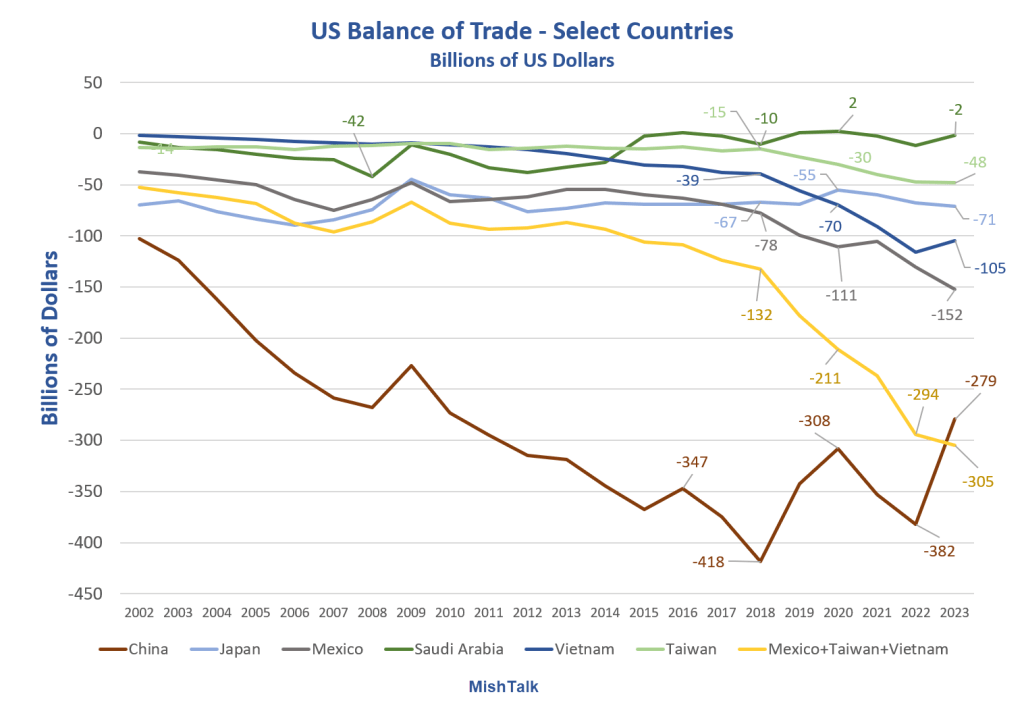

Chinese exports to the United States are down since the 2018 introduction of the Trump tariffs, as are China’s reported holdings of U.S. Treasury and government-backed agency bonds. But those indicators are poor measures of these two economies’ true interconnection. When considering the impact of the United States’ much-ballyhooed bilateral tariffs on Chinese products, it is important to look beyond U.S. data showing a fall in direct imports from China and pay more attention to data from China itself. Surprisingly, those data reveal a much smaller decline in direct trade with the United States and a steep rise in Chinese exports to countries that are now exporting more to the United States.

U.S. policymakers are rightly concerned that the world has become too reliant on China for supply, particularly with respect to clean energy and green technology. In a mid-May speech, Lael Brainard, the director of the U.S. National Economic Council, put it well: “China’s industrial capacity and its exports in certain sectors are now so large that they can undermine the viability of investments in the U.S. and other countries. … Markets need reliable demand signals and fair competition for the best firms and technologies to be able to innovate and invest in clean energy and other sectors. The Chinese government has made clear that China’s massive investments in electric vehicles, solar panels, and batteries are an intentional strategy to effectively capture these sectors.”

Those who worry about deglobalization also often assume that all forms of economic integration are healthy. But they are not: the surge in cross-border bank flows before the global financial crisis, for example, reflected an unhealthy level of leverage and risk in the world’s big banks. Today, too, an excessive amount of the world’s FDI flows merely reflect tax avoidance, not productive economic activity.

There is also an opposing risk: that if policymakers do not acknowledge the degree to which globalization persists, they will grossly underestimate the shocks that would stem from a fuller decoupling of Chinese and U.S. trade.

Deglobalization offers analysts a simple story to tell about changes to the global economy. But the reality is more complex: put plainly, it is impossible for a global economy characterized by a large U.S. deficit on one side and a large Chinese surplus on the other to truly fragment. The world needs to have a healthy debate about the drawbacks and benefits of economic integration. But that debate must start from a frank acknowledgment that many characteristics of the contemporary global economy still push toward more, not less, integration, and that addressing these factors will have real costs.

How Do We Measure Globalization?

I scarcely disagree with anything Setser said. But what is globalization and how do we measure it?

If Chinese exports are the measure of globalization then where are nowhere near a decline in globalization.

Without defining the term, here are a few things I associate with globalization: Free trade, global wages arbitrage, just-in-time manufacturing, reduced trade frictions, rising standards of living, belief that the next generation will be better off than you are, and disinflation.

What, if any of that, is happening now?

US Balance of Trade

To avoid US tariffs China exports to Mexico or Vietnam which then export to the US.

Is that a sign of globalization? Does that add anything but costs?

Consumer of Last Resort

The US is the word’s consumer of last resort. That is one thing that has not changed. And it is a direct result of having the world’s reserve currency fueled by Nixon ending the last piece of the gold standard.

If countries insist on export mercantilism, the US has three choices, all of them bad, but the least bad (judging by the option the US has chosen) is a ballooning deficit.

Pettis on the Ballooning Deficit

The Choice

Excess Savings?!

It’s hard to think of massive debt everyone funded by printed dollars (yuan, yen, euros) nearly everywhere, as “excess savings”.

I define savings as “Production – Consumption” and I struggle to define printing dollars or yuan as either “production” or “savings”.

However, I agree with Pettis that we do have a massive global imbalance, hyper-financialized as a direct result of the end of the gold standard and China’s (also Germany’s) explicit policies.

Germany is feeling the pain of reversal now. And China refuses to do anything to alleviate the imbalances.

Under a gold standard the US could not have these deficits without losing its gold or jacking up interest rates. Now, there are no global curbs in place.

As a result of China’s policy, Chinese consumers are subsidizing US consumers to the benefit of Chinese exporters, US (global) consumers, and the detriment of Chinese consumers and US businesses.

As Setser notes, and my chart shows as well, tariffs have not done a thing. All we have accomplished is to increase trade frictions to the melting point.

Trade Friction Melting Point

Pettis: “Surging US fiscal debt is needed mainly because the alternatives – surging US unemployment or surging household debt – are worse.”

That trio of alternatives led to terrible fiscal policy under every president, inept Fed policy, tariffs by Trump and Biden, nonsense like the Inflation Reduction Act, and calls for more military spending by both parties because hardly anybody remotely understands what’s going on or why.

Perverted Economics

I hesitate to call what’s happening now “globalization” because it has little to do with ideas we should associate with globalization.

Perverted economics is more like it.

The gold standard was an automatic brake on perverted economics. There are no brakes in place now.

Chip Wars, China’s Goal Is to Cut Out the US

On June 4, I noted Chip Wars, China’s Goal Is to Cut Out the US

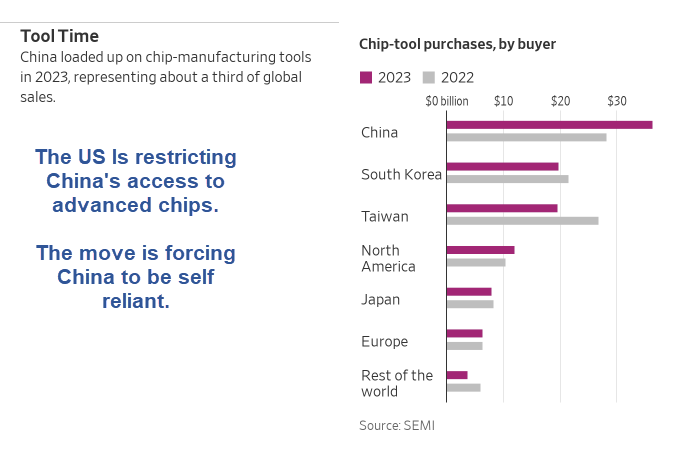

The US is restricting China’s access to advanced microchips. The US will regret the move in one of two ways. China will become self-reliant or there will be a real war.

A reverse title is also true. The goal for the US is to Cut out China.

So far, neither the US not China has cut off chip access to the other, but Biden is desperately trying.

We need to hope he doesn’t succeed.

Computer Chip Sanctions Fail

On September 4, 2023, I noted US Sanctions Fail Again, China Now Produces Its Own Advanced Computer Chips

Trump and Biden both tried to cut off China’s supply of advanced microchips. The US wanted to knock Huawei out of the 5G market. Now, instead of China using US chips, it is producing its own chips.

China Bans iPhone Use for Government Officials

On September 7 2023, in response to US actions, I asked China Bans iPhone Use for Government Officials, Just a Start?

On February 18, 2024, I discussed How China Gets Around US Sanctions on Semiconductors

The US is far ahead of China on technology, but China is gaining ground faster than anyone thought.

The US wanted to restrict China’s access to 7nm chips but now it appears China is making its own 5bn chips, and the smaller the better.

When Trade Ends, Wars Start

One of the Three Reasons Japan Attacked Peal Harbor was the US cut off Japan’s access to oil and natural resources. War became inevitable. Japan chose to strike first.

The US and China are in a global trade war. And the EU is on the verge of joining that trade war, egged on by the US.

However, the end game is easy to spot. Either China will be successful at advanced chip production at a pace that satisfies China, or China will move to take Taiwan by force.

Is Globalization Fine and Dandy?

Globalization may not be “dead” but it’s increasingly perverted rather than alive and well.

The irony is people believe us trade deficits will result in the rise and dominance of a BRICS currency.

However, the yuan does not float, China does not want to have the global reserve currency because it is incompatible with export mercantilism, and fundamentally trade is between individuals not nations (what individual wants a BRIC rather than a dollar or euro?)

For discussion, please see What Would it Take for a BRIC-Based Currency to Succeed?

Yet every month we hear more silliness about US deficits leading to a rise of a BRICS currency.

The current path is unsustainable. But I have no idea how long it can or will continue. No one else does either.